Valuing Serendipity: Joel Chadabe’s Interactive Music Systems

As I was browsing the website of electronic composer Joel Chadabe, I was drawn to a link on the homepage titled, “Advice: You Can Do Anything.” The last sentiment shared in this statement of advice from one composer to a future generation of others caught my eye: “Value serendipity. If an accident happens and you like it, keep it.” Too frequently, accidents or mistakes in music are expected to be fixed or apologized for. Chadabe’s respect for relinquishing control makes sense in the context of his career as a pioneer of interactive music systems. Much of his music and electronic innovations required him to grant control to and respond to the computer programs he interacted with, creating a symbiotic relationship between man and machine that defied the typical dominance of a musician over their instruments.

Born in 1938, Joel Chadabe grew up in the Throgs Neck neighborhood of the Bronx. Although he initially wanted to be a lawyer, he eventually decided to study music at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. After graduating in 1959, he furthered his compositional education at Yale University, learning from the renowned modernist composer, Elliott Carter. While studying in Italy with Carter, Chadabe heard of a job opportunity at the State University of New York, Albany and returned to the States to begin his career.

One year into his position at SUNY, Chadabe’s career took an unexpected turn in 1966 when SUNY asked if he would be willing to build and run the university’s first electronic music studio. Although Chadabe hadn’t set out to compose electronic music from the start, he said, “It was the new frontier of music, and I saw unlimited possibilities.” He got to work making it happen, collaborating closely with synthesizer engineer Bob Moog who lived only a few hours away in Trumansburg. Initially, Chadabe didn’t receive enough funding from the university and was only able to buy a partial synthesizer that ran on a car battery.

During this period, Chadabe began composing his first electronic pieces, the first of which was titled Blues Mix (1966). Chadabe’s initial interests before diving into electronic music included jazz, opera, and musicals, which greatly influenced how he wrote electronic compositions such as Blues Mix. For this piece, Chadabe connected two Moog oscillators so that they automatically controlled one another. Then, Chadabe turned a knob throughout to adjust their frequencies, responding to the oscillators’ actions. Chadabe said of the piece, “It was a playful experiment on my part, and to my knowledge it was the first time a composition was created in this way.” Blues Mix was an early vision of the interactive music systems he would create a few years later.

Once more funds came through in 1968, Chadabe and Moog were able to build a “super synthesizer,” the largest interconnected group of Moog synthesizers which came to be known as the CEMS: Coordinated Electronic Music Studio. The modules of the CEMS were divided into three categories that performed different functions: (1) the audio system, which included machines such as oscillators, amplifiers, and mixers, (2) the control system, which performed functions like envelope generation, and (3) the timing system that created pulses for the CEMS to work from. Unlike other Moog inventions, the CEMS was not controlled from a musical keyboard. With the CEMS complete, Chadabe would wait until students left the music building for the day and stayed up experimenting with CEMS until late in the evening. These nights brought Chadabe closer and closer to electronic innovations.

Prior to this point in electronic music’s history, computer music was progressing rapidly. Figures like Lejaren Hiller used a computer to create a computer-generated string quartet in 1957, the Illiac Suite, to be performed by an acoustic ensemble. Max Mathews developed multiple groundbreaking programs throughout the sixties with his MUSIC series. He also wrote the accompaniment for the 1961 “Daisy Bell” performed by the earliest synthesized human voice on an IBM 704.

Continuing to build upon the work of his contemporaries, Chadabe was at the forefront of interactive approaches to computers and synthesis in composition. Beyond telling the computer what to do via a program, Chadabe listened and responded to the computer in real time, almost like an improvising duo. In Chadabe’s words, “The performer, in turn, influenced the instrument by performing. A performer and an interactive instrument have a relationship that is conversational.” The primary way through which Chadabe influenced and interacted with random music created by the system was through joysticks.

The best example of this technique is in his piece, Ideas of Movement at Bolton Landing (1971). Inspired by the Wallace Stevens poem, The Idea of Order at Key West, and the sculptures of artist David Smith, Chadabe said, “The logic of the words and their sequence in Stevens’ poem, and the forms and links of the steel shapes in Smith’s sculptures, suggested to me the special sequence and character of sounds that I was composing.” In Ideas, Chadabe used joysticks to change either speed, pitch, density (of musical texture), and spatialization utilizing the four directions of the joystick. Chadabe cites this piece as the first example of what he called, “interactive composing.”

During the seventies, Chadabe arranged for many notable figures in avant-garde music to come perform at SUNY, such as Julius Eastman and Alvin Lucier. Others would come to SUNY to use the electronic music studio, such as Kraftwerk, Genesis, and Depeche Mode. These three groups were drawn specifically to the Synclavier digital synthesizer Chadabe had acquired for the studio. The most notable figure to use the SUNY electronic music studio for composition was John Cage, who traveled to SUNY in 1972 to write his piece, Bird Cage.

Cage brought with him three groups of tapes which each contained different types of material. Group A contained recordings of birdsong from aviaries, Group B was Cage singing and chanting his piece, Mureau, and Group C captured environmental sounds. Working with Chadabe and one of Chadabe’s students, Cage directed them to switch out which tapes played into the recorder according to a timesheet he had created prior to recording. Once the piece was finished, it was prepped for performance in the concert hall and was premiered in December 1972 at SUNY Albany.

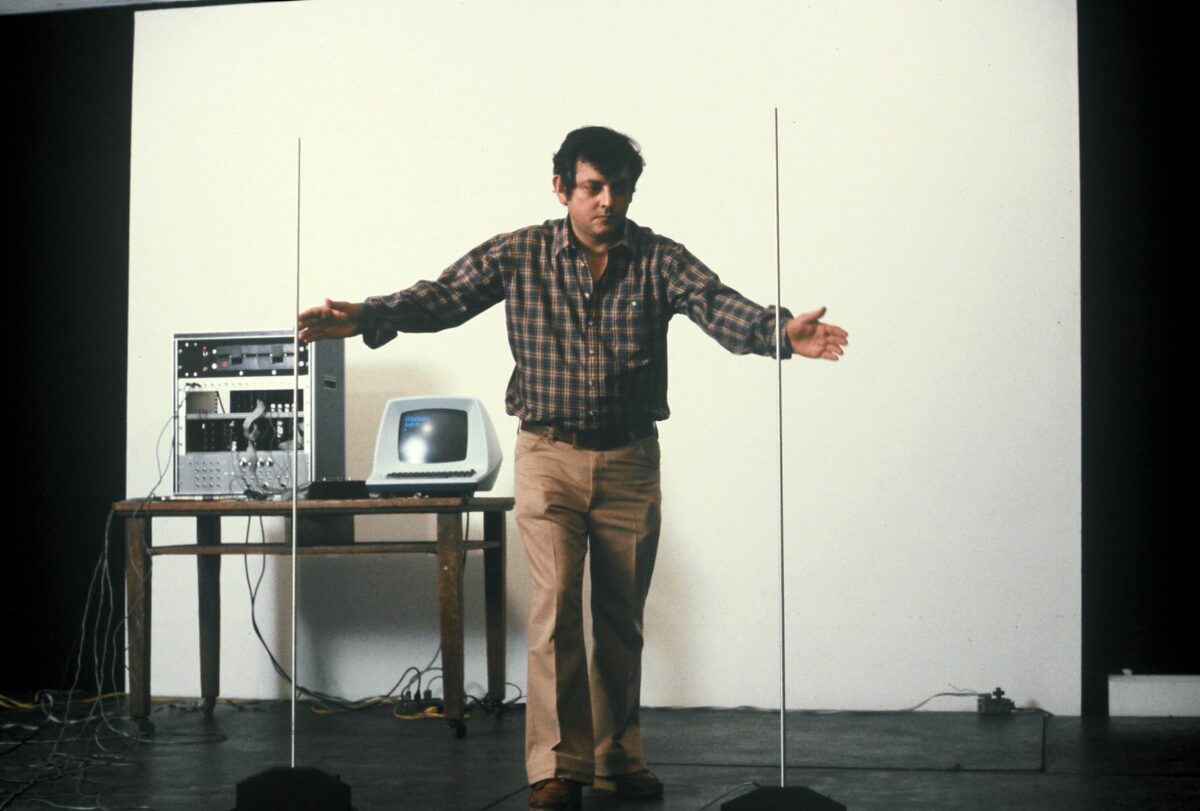

By the end of the decade, Chadabe expanded his concept of interactive composing into a larger spatial arrangement with more functionality in his composition, Solo (1978). Inspired by how a theremin functions, Chadabe asked Bob Moog to build two antennae based on a theremin antenna, which Chadabe then connected to a computer and Synclavier. He programmed eight voices – two clarinets, two flutes, and four vibraphones – and controlled elements of tempo and timbre with the two antennae. The left affected the tempo of the musical output, and the right antenna allowed Chadabe to switch the computer software patches to different timbres, an early example of being able to change musical timbre in computer music in real time. Chadabe referred to the entire result as an “improvising orchestra,” in which the computer chose pitches and he would react live to the software’s decisions. The setup for Solo was installed at the New York State Performing Arts Center so that the public could learn about it and try it for themselves.

Using computers to compose music in the seventies remained in the realm of the electronic music studio, but in the eighties with the rise of personal computers, Chadabe began developing software that individuals could use to compose music on their computers at home. He founded the company Intelligent Music, which produced the softwares M, Jam Factor, and UpBeat, the latter of which was used by New Order for their album, Technique (1989).

In the nineties, Chadabe began reflecting on the role of electronic music in the recent history of music. He founded the Electronic Music Foundation in 1994, which strove to preserve the legacy of electronic music and nurture its future. EMF hosted concerts of individuals such as Laurie Spiegel, Iannis Xenakis, and Chadabe’s previous collaborator, John Cage. They also maintained an online CD store to circulate recordings of electronic music. Chadabe also published the book, Electric Sound: The Past and Promise of Electronic Music, in 1997, documenting conversations with essential figures in electronic music up until that point, including Bob Moog, Max Mathews, Pauline Oliveros, Morton Subotnick, and David Tudor.

Chadabe also became a fervent environmentalist in the 2000s, starting the Ear to the Earth festival, which featured music that interacted with nature and environmentalism. His concept of the connection between humans and nature de-centered human perception of sound. As Marc Battier said in his article, “The Emergence of Interactive Music: The Vision and Presence of Joel Chadabe,” “He wanted to use the microphone to capture environmental sounds that our perception was missing because of our built-in way of focusing on some sounds while masking the rest. He was aware that, contrary to human perception, the microphone captured all sounds without discrimination.”

Throughout all of Chadabe’s work, he deeply believed in the sharing and preservation of electronic music. He passed away last year at age eighty-two. A few years before he died, he wrote these words as the introduction to his website: “In 2018, looking back, I realized that a new world of music had developed between 1950, when the first tape recorders appeared in radio stations, and 2000, when analog and digital synthesizers were everywhere. It was fifty years of new technologies and new ideas for sounds and instruments. Thinking of that, it occurred to me that those of us who were actively involved in music during that time should tell our stories as individuals to convey to future generations of students how it all happened…For me, creating music with electronics has meant exploration, discovery, creativity, research, performance, and sharing knowledge and ideas with others in a new world of sound. My goal is to share those attitudes and activities with students and colleagues into the future.”

We recently stocked each volume of the Electronic Music Foundation CD series of Joel Chadabe’s work here at the shop. Grab a CD or four, have a listen, and explore his essential contributions to electronic music’s legacy. I also highly recommend exploring his website, which was immensely helpful in writing this blog post, and also includes even more of his insights into his work than I could fit here.

In the Shop

Joel Chadabe – Chadabe & Moog CD – $12

Joel Chadabe – Electric Sound CD – $12

Joel Chadabe – Intelligent Arts CD – $12

Joel Chadabe – Dynamic Systems CD – $12

Interested in more modern composition, musique concrète, or electronic music?

Resources

Marc Battier, “The Emergence of Interactive Music: The Vision and Presence of Joel Chadabe,” Leonardo (2022)

Joel Chadabe, Electric Sound: The Past and Promise of Electronic Music (1997) (online)

David A. Jaffe, “Remember Joel Chadabe,” Leonardo (2021)

Peter Shea, “Joel Chadabe, Composer, on Interactive Systems, February 2013,” University of Minnesota (2013)

Alex Vadukul, “Joel Chadabe, Explorer of Electronic Music’s Frontier, Dies at 82,” The New York Times (2021)

– Hannah Blanchette

September 23, 2022 | Blog