-

×

Devouring The Guilt - Not to Want to Say

1 × $12.00

Devouring The Guilt - Not to Want to Say

1 × $12.00 -

×

Matt Adis - Heads Of The Malnourished

1 × $20.00

Matt Adis - Heads Of The Malnourished

1 × $20.00

Subtotal: $32.00

Click images to enlarge

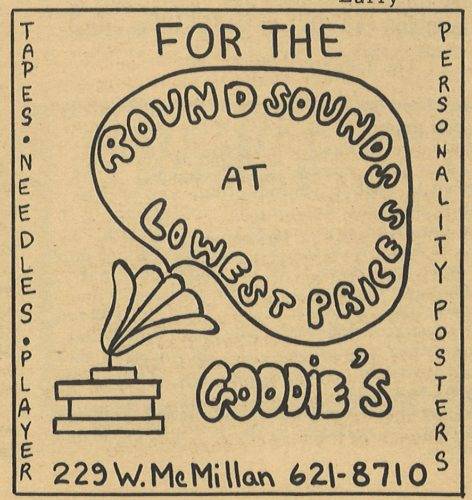

Mark said, “There was probably one person on the staff who could draw a little bit, so they just took a Sharpie and did this little quick doodle and wrote the phone number.”

Delicate flowers drawn near the margins. Handcrafted ads for psychedelic rock shows, hippie gift shops, and esoteric bookstores that once sat on street corners I walk past regularly. Janis Joplin at Music Hall, Iggy Pop at the Ludlow Garage. The care towards crafting The Independent Eye, Cincinnati’s progressive underground paper that ran from 1968 to 1975, was one part of the paper that caught my eye. The other part that captured me was how the Eye seemed to depict a version of the Clifton neighborhood that is vastly different from how it is now, one firmly in the grasp of the sixties counterculture. And yet, if people hawked the Eye on street corners today, we would grab a copy and read articles that still resonate in 2022, pages filled with anti-war cries, demands for women’s, Black, and LGBTQ rights, and calls for action against police brutality.

About a month ago we adopted three issues of The Independent Eye into our Torn Light archival collection, and since then I’ve had the opportunity to speak with local artist Mark Neeley, who researched and curated the Independent Eye exhibition and panel at the Cincinnati & Hamilton County Public Library in 2019 and collaborated with Jon Flannery and many local artists to create Optic: A Visual Tribute to the Independent Eye, published in 2020. We talked about the development and role of underground press in the late sixties and early seventies, how the Eye interacted with the Cincinnati music scene at that time, and parallels between underground and progressive culture then and now.

The Independent Eye was founded in Yellow Springs, Ohio by Antioch College seniors Alex Varone and Jennifer Koster in 1968, moving to Cincinnati not long after. The paper’s main purpose was to print progressive news, especially protesting the Vietnam War at the start. Hippies hawked the Eye in Clifton and downtown Cincinnati, countercultural hotspots at the time. The Eye belonged to a broader trend of underground papers cropping up across the United States during the sixties, some notable examples including New York City’s paper, East Village Other and San Francisco’s Haight Ashbury publication, the Oracle. Mark and I discussed how these underground papers were some of the first of their kind, early examples of alternative news sources and alternative subculture. In the sixties, print news was still the primary means of circulating current events. Mark said, “Every town had their local paper, and then there was the big national papers. And with these really contentious things happening, specifically the war in Vietnam, a lot of people that were involved in those same movements, where there was counterculture through the music or other print forms even, I think it was a logical next step. What if we could have an underground press?”

Mark further described how alternative press wire services were established to provide national news stories to these underground papers. “One of the big ones was called ‘The Alternative Press Syndicate.’ They were essentially this small organization that would write national news stories, whether it was about racial injustice or Vietnam specifically or whatever the case may be, and then they would provide those and send them out to all the local papers all over the country. So that’s why in the Eye or any paper you have local stories and these ones that are more national. It was like the AP, but underground.”

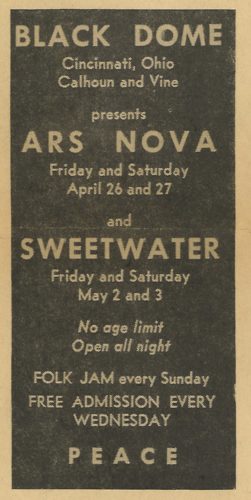

Having an underground press developed other aspects of underground culture. For the Eye, psychedelic art adorned its pages, advertisements promoted prog, psych, and folk rock shows, and personals connected people across the city via addresses and phone numbers, all reflecting a vibrant underground scene in the Eye’s midst, if not created and strengthened through it. “I think you look at this and you see the very beginnings of zine culture. Literally,” Mark stated. “Nothing like this existed before these papers. The music scene, all these venues we were talking about didn’t exist before the Black Dome came along.”

Clifton’s Black Dome was the music venue when the Eye started, bringing in acts like Procol Harum (who were also interviewed by the Eye in 1969), John Mayall, James Gang, Ars Nova, Sweetwater, and Alice Cooper. Despite hosting great shows that initially were well-attended, the Black Dome’s reputation became tarnished over time due to stereotypes about hippies and the counterculture. The Black Dome went under around the time that the Ludlow Garage arose as the primary Clifton venue, with even a piece in the Eye covering this, “The Cincinnati Music Scene and the Death of the Black Dome.” The author, music reporter Bill Hobson wrote this biting commentary, “Contrary to many popular beliefs, Cincinnati does not have a sizable head population; anyway, not one that does support rock concerts. Cincinnati only has sizable apathy and paranoia.” Hobson gestures towards both the small subculture that heads had within the larger city culture, and that not enough of them were actively supporting music, especially due to rising ticket prices. (I can’t deny how uncannily familiar that is within today’s streaming culture for both music and film). Over time, the Black Dome lost its recognition as a historically relevant venue to music in Cincinnati. “There’s obviously such a rich history with especially Black music in Cincinnati with King Records and the Cincinnati jazz history,” Mark said. “Getting into the late sixties, I think a huge turning point was when a venue called the Black Dome opened. A lot of people remember the Ludlow Garage, not only because it still exists in some capacity, but the Black Dome was really the first one.” It is important to mention that Steven Rosen’s new book, Lost Cincinnati Concert Venues Of The ’50s And ’60s, covers the Black Dome, bringing its history back to the fore.

Clifton’s Black Dome was the music venue when the Eye started, bringing in acts like Procol Harum (who were also interviewed by the Eye in 1969), John Mayall, James Gang, Ars Nova, Sweetwater, and Alice Cooper. Despite hosting great shows that initially were well-attended, the Black Dome’s reputation became tarnished over time due to stereotypes about hippies and the counterculture. The Black Dome went under around the time that the Ludlow Garage arose as the primary Clifton venue, with even a piece in the Eye covering this, “The Cincinnati Music Scene and the Death of the Black Dome.” The author, music reporter Bill Hobson wrote this biting commentary, “Contrary to many popular beliefs, Cincinnati does not have a sizable head population; anyway, not one that does support rock concerts. Cincinnati only has sizable apathy and paranoia.” Hobson gestures towards both the small subculture that heads had within the larger city culture, and that not enough of them were actively supporting music, especially due to rising ticket prices. (I can’t deny how uncannily familiar that is within today’s streaming culture for both music and film). Over time, the Black Dome lost its recognition as a historically relevant venue to music in Cincinnati. “There’s obviously such a rich history with especially Black music in Cincinnati with King Records and the Cincinnati jazz history,” Mark said. “Getting into the late sixties, I think a huge turning point was when a venue called the Black Dome opened. A lot of people remember the Ludlow Garage, not only because it still exists in some capacity, but the Black Dome was really the first one.” It is important to mention that Steven Rosen’s new book, Lost Cincinnati Concert Venues Of The ’50s And ’60s, covers the Black Dome, bringing its history back to the fore.

Amongst Black Dome advertisements, there are so many articles about music that piqued my interest while flipping through the public library’s first volume of Eye issues, such as a 1969 article by Melvin L. Grier, “WCIN: Sell-Out Radio,” which critiques how the Black community is depicted through this local radio station, Robert A. Rouda’s 1969 article, “Offering: John Coltrane,” which enthusiastically returned to his record Expression and sang its praises, and the Eye’s coverage of music festivals such as the Atlantic City Rock Festival and Midwest Minipop Festival. Concert and album reviews also abounded, such as a review of Janis Joplin’s performance at Music Hall with scathing comments about locals, The Sacred Mushroom. I began picking up on who their regular music reporters were: Joan Adler, Bill Hobson, Ken Hawkins. And all of this from only about a third of the Eye’s total issues. Through his research, Mark found out how much music was happening outside of the standard rock venues. “There was this hippie coffee shop in Westwood where they would host folk rock concerts. There would be rock concerts at that pavilion outside the art museum. You see a lot of that peripheral stuff that didn’t just happen at the rock venues.”

The Eye continued publishing until 1975, although it faced its share of hardships as the years went on, including an arson fire that devastated their Vine Street office in Cincinnati and placed the Eye staff under extra duress. However, the fact it remained active for seven years was a feat for countercultural publications at that time. Mark said, “The fact that it was published from early February of ’68 through ’75 makes it really unique for those kind of papers. Because most of them, because they were done on a shoestring budget, etc., they would flame out after like, a year. Most of these were like ’68, ’69, maybe into ’70. But Cincinnati, the Eye, was one of the longest ones. It was seven years. And also, the culture changed so much by 1975. It’s amazing that it lasted that long.”

Mark and I also wrestled with the question: why does The Independent Eye matter? There were so many other underground papers across the United States that captured sixties counterculture, why celebrate the Eye? We talked about how much of US music history focuses on contributions from the coasts and major city centers, i.e. punk in New York City, psychedelic rock in San Francisco, East Coast vs. West Coast rap, etc. Clearly, time complicates these ideas and we know about how music developed throughout the nation. Regardless, it is still essential to acknowledge how culture in the Midwest functioned and contributed to larger narratives during a time period as contentious and creative as the sixties counterculture.

Clifton is a bit different now than the version of it that the Eye writers talked about, shops that were advertised every week now long gone and so many discussions of social activism and politics moved to online spaces. Much of Clifton Heights is devoted to places for university students to study and socialize, and while remnants of the counterculture can be seen in the Gaslight District, such as the fountain at the Clifton/Ludlow intersection, Ludlow Avenue has gone through many transformations as well. Despite these changes, I think Clifton, and Cincinnati as a whole, still have an underground presence, and one that exists in physical spaces. The Eye is a large part of that history that went unacknowledged for decades. Its fade into obscurity was partially due to frail copies of the paper being stored by the public library amongst its rare items, kept safe but harder to access and peruse.

Clifton is a bit different now than the version of it that the Eye writers talked about, shops that were advertised every week now long gone and so many discussions of social activism and politics moved to online spaces. Much of Clifton Heights is devoted to places for university students to study and socialize, and while remnants of the counterculture can be seen in the Gaslight District, such as the fountain at the Clifton/Ludlow intersection, Ludlow Avenue has gone through many transformations as well. Despite these changes, I think Clifton, and Cincinnati as a whole, still have an underground presence, and one that exists in physical spaces. The Eye is a large part of that history that went unacknowledged for decades. Its fade into obscurity was partially due to frail copies of the paper being stored by the public library amongst its rare items, kept safe but harder to access and peruse.

At the end of this post, I’ve included links to every resource about The Independent Eye that are available digitally to the public through the library, including scanned PDFs of every issue of the Eye. “I think the ultimate thing I’m most proud of is that we created that digital archive,” Mark stated “That’s the permanent part of it. It’s not just like there was this event, or this was published, there’s only so many issues. Now if you want to look, it’s there. It had basically been locked in a vault for the past fifty years.” You can also learn more about the Eye’s history through its CityBeat feature, watch the Independent Eye panel hosted by the public library (which features many stories from former Eye staff members), and flip through the incredible local art created for the Optic tribute to the Eye. The images in this post are sourced from the specific copies of the paper that we have in our archives at Torn Light. The “vault” has been opened.

Take a closer look, click to enlarge:

Independent Eye, v. 1-2 (1968-69)

Independent Eye, v. 3 (1970-71)

Independent Eye, v. 4-8 (1971-75)

Mackenzie Manley, “The Independent Eye,” CityBeat (2019)

Optic : A Free Press Tribute to the Independent Eye, v. 1 (2020)

A very big thank you to Mark Neeley for sharing his insights on the Eye!

– Hannah Blanchette

May 29, 2022 | Blog