Topic Records, Industrialization, and the Second British Folk Revival

In Ohio, I find that the distinctive, autumnal chill in the air comes a bit later than I’m accustomed to from my early life in New England. It’s only in the past week or so that I’ve felt that characteristic crispness curl up through my nose and settle in my lungs. The idea for this blog was triggered by an Instagram post from our very own account, which displayed the entire Pentangle catalog in stock at the shop. Described as “perfect for the fall,” I internally agreed that British folk music was the perfect backdrop to the seasonal shift and subconsciously started digging back into Pentangle, Fairport Convention, Bert Jansch, Anne Briggs, and the like while on my walks around the neighborhood. I thought it would be fun to do a brief history of one of the most essential record labels to the second British folk revival, Topic Records, which is still in operation and bringing contemporary British folk to our turntables. Also, their website proudly claims they are the oldest independent label in the world, founded in 1939. They state they are waiting for another label to swoop in and prove them wrong, so until that time I’ll believe them.

Two important aspects of Topic Records’ history that I learned through my research are the label’s inextricable relationship with socialism and the labor union movement in the United Kingdom, as well as their significance in reconceptualizing folk music as a genre that can speak to topics of urban life and industrialization, as much as it evokes rural settings. The pastoral associations we still often attribute to British folk music derive heavily from the British folksong collector Cecil Sharp, a both influential and controversial figure in English and Appalachian folk music history. His romanticization of folk music as the most authentic when sourced from rural locations is one of the areas of his work that is frequently critiqued. Topic Records played a role in unsettling this notion and expanding the concept of folk music as untethered to an environment, but rather tied to ideas and the concerns of the working class.

The label initially began as the Topic Record Club associated with the Workers Music Association, an organization founded in 1936 by London composer and professor Alan Bush as a group to promote the expression of political ideas, especially those related to labor organizations and trade unions, in works of music and theatre. In 1939, the first record released by the affiliated Topic Record Club was a 78-rpm record of “The Man That Waters Down The Workers Beer” by Paddy Ryan, an explicit protest against the exploitation of workers. Post-war, the Topic Record Club began to shift its focus towards folk music in tandem with the growing American folk revival movement and the influence of folk archivist Alan Lomax from overseas.

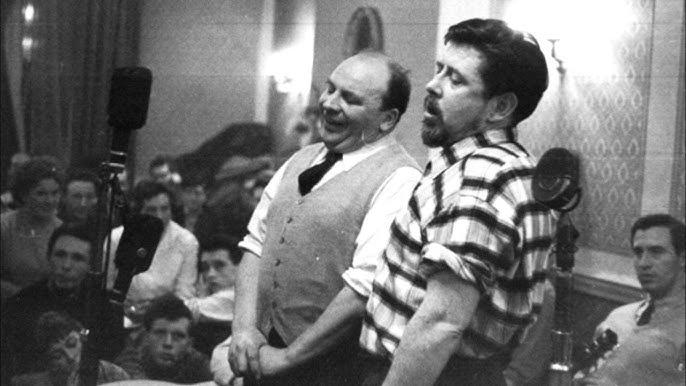

It was around this time that two of the most influential figures in this second British folk music revival, Ewan MacColl and A.L. Lloyd became more involved in the Workers Music Association and Topic Records, so that Topic began to shift its focus towards becoming a label instead of the limited release approach of a record club, as well as becoming the home for licensing American releases from musicians such as Pete Seeger, Woody Guthrie, Peggy Seeger, and Sonny Terry & Brownie McGhee. Topic’s own recordings were frequently captured by their production manager, Bill Leader, who was willing to make a recording space out of anything, capturing the free spirit of folk music recording sessions of the day. The Workers Music Association did have a studio in their headquarters, but records were sometimes laid down at MacColl’s house or from setting up recording equipment everywhere and anywhere.

MacColl and Lloyd were both individuals who, in tandem with Topic Records, worked to employ folk music as a channel for the experiences and protests of urban, working class people in the United Kingdom, drawing upon music from the industrial revolution versus that of the idyllic countryside. Lloyd in particular was opposed to the ways folk music had been made quaint and docile, and as stated in Topic Records’ official biography, he “attack[ed] middle class pretensions of folk song as represented by the establishment in general and the English Folk Dance & Song Society in particular.”

In my experiences within academic and classical music spaces, I have to say I find this concept to be all too often true. There is a long history of folk music from various nations becoming displaced from its roots and mined for a composer’s musical inspiration, or placed under a microscope for analysis without understanding the impact of the music within its own environment. What I believe figures like Lloyd were accomplishing was highlighting the folksong’s relevance to contemporary life, allowing it to speak on behalf of working class people, and forming folk community in urban spaces.

As Topic Records’ name suggests, their early folk recordings often centered on literal topics. One of the records that reflects the focus on folk music and industrialization was the Iron Muse collection from 1963. It featured performers such as Anne Briggs, Bob Davenport, Ray Fisher, Louis Killen, and Matt McGinn, its program by Lloyd sharing folksongs that were derived from mills, factories, and mines. As Colin Irwin beautifully phrased it in the Topic Records bio, the collection, “hammered home the argument that far from being the preserve of rural communities, folk music also belonged to factory workers and had an important role in the urbanization that resulted from the industrial revolution.”

With the above mention of Anne Briggs, I am going to make a move towards my personal bias and discuss my favorite Topic Records release (although I believe an overview of Topic’s history would be remiss without talking about it), Briggs’ self-titled album from 1971. A British folk performer of immeasurable influence, while remaining a vexingly enigmatic figure, Anne Briggs was introduced to the world of folk recording through the Iron Muse compilation. She became a staple in the British folk club circuit, collaborating with Bert Jansch and inspiring individuals such as A.L. Lloyd, June Tabor, Sandy Denny, and Richard Thompson.

I see in Anne Briggs’ work the tension between the urban and rural in British folk performance during the second folk revival. While she contributed to the Iron Muse and was omnipresent in urban folk club settings, much of her music dug back into the pastoral imagery oft associated with folk music. Her self-titled’s album cover depicts her abstractly sketched, walking along a path with a dog at her heels. While she is seemingly out in nature, there is an ambiguity to that cover; maybe she is walking on a city street? Selections on the record such as “The Snow It Melts the Soonest,” “Thorneymoor Woods,” and “Living By the Water” depict human interactions with natural landscapes, while others such as “Blackwater Side,” “Willie O Winsbury,” and her self-penned “Go Your Way” ruminate on the complexities of relationships.

There is a delicate tug between historically faithful, traditional folk performance and the employment of folksongs as representations of modern life, and balancing these elements is a perennial task of the contemporary folk singer. But was it not Topic’s goal to prove the continuing relevance of centuries-old folk music to current life? I believe it is safe to say that their persistence through more than eight decades of change, in both the recording industry and the world, proves that they have countless times achieved that goal.

– Hannah Blanchette

November 3, 2024 | Blog