The Present Inside the Past: Hauntology and the Disintegration of Public Memory

When I listen to “Wildlife Analysis,” the opening track of Boards of Canada’s Music Has the Right to Children, it resonates within me in a way that transports my mind beyond 1998, beyond Boards of Canada. There is an uncanny sense that I have heard it before somewhere, maybe in a PBS documentary left on after everyone else has gone to bed. I imagine this experience is similar for many who listen to artists such as Warp’s Boards of Canada and even Broadcast, William Basinski, the Caretaker, or any of the crew at the Ghost Box label. Part of the magic of musical artists that fall under hauntology is how they evoke elements of cultural memory, creating eerie facsimiles or distortions of familiar sonic characteristics.

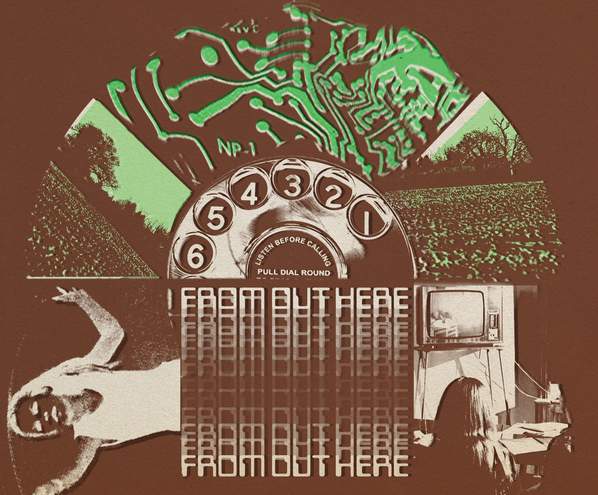

The source materials for most in hauntology reflected, as Simon Reynolds puts it, “the spirit of technocratic utopianism that flourished in post-war Britain,” drawing on library music, public service announcements, and early electronic experimentation such as the BBC Radiophonic Workshop. The resulting music focused on evoking British public space and media experiences, especially musical cues which were initially forgettable, but retain an uncanny sense of familiarity. American analogs to the British sources of hauntology such as PBS programs can elicit similar responses in American listeners as well. At some point as the television rose in popularity, a common musical language in the form of library music and futuristic electronics set the tone for publicly available documentaries, PSAs, and children’s programming.

The musical cue that continues to strike me to this day is the WGBH logo cue, which appeared at the end of television programs distributed by the popular Boston-based PBS station, something I probably heard every day at one point in my childhood. Even outside of the New England region, its rush of electronic flourishes, originally composed by Moog pioneer Gershon Kingsley, conjure deep nostalgia for a wide range of individuals. Because of the ubiquity of public television, and of the television altogether as the primary carrier of mass media from the mid-twentieth century onwards, the sonic characteristics of objects as simple as the WGBH logo wove themselves into the shared memory of many Americans. Julian House, one of the founders of Ghost Box, considered “TV as a sort of dream machine, [connecting] our shared memories and collective unconscious.”

Mass media gradually seems to be shifting away from traditional network television towards social media, taking our “collective unconscious” right along with it. While the intent of the Internet was vast connectedness, I believe that this shift is causing shared public memory to dwindle, as American society (although I can only speak to experience in the US, I imagine this is happening to many other societies) shrinks down into an extremely individualized, algorithmically based media landscape that erodes publicly shared media experiences, including music and sound. As these source materials dry up or lose their evocative power, what role could hauntology play going forward? What is the next public musical space that will come to haunt us in the future? While there may be viral trends and widely shared memes in our current landscape spanning TikTok, YouTube, and others, the days of every American in your region with a television set seeing the same public service announcement or same news broadcast are over.

What is the future of any music which relies on public memory? This question is something that goes beyond the typical concerns about “retromania,” to once again quote Simon Reynolds. It is no surprise that the music industry has been mining the past and reworking it for the present for decades now. With retromania, something like the post-punk revival harkened back to a specific subgenre within music, whereas hauntology grasps for pieces of widespread, past public musical experiences encountered in everyday life. Retromania is concerned with recycling to the point of having nothing new to recycle, which could effect hauntology too. But additionally, hauntology’s materials are sourced from a public sphere which is increasingly becoming “private.”

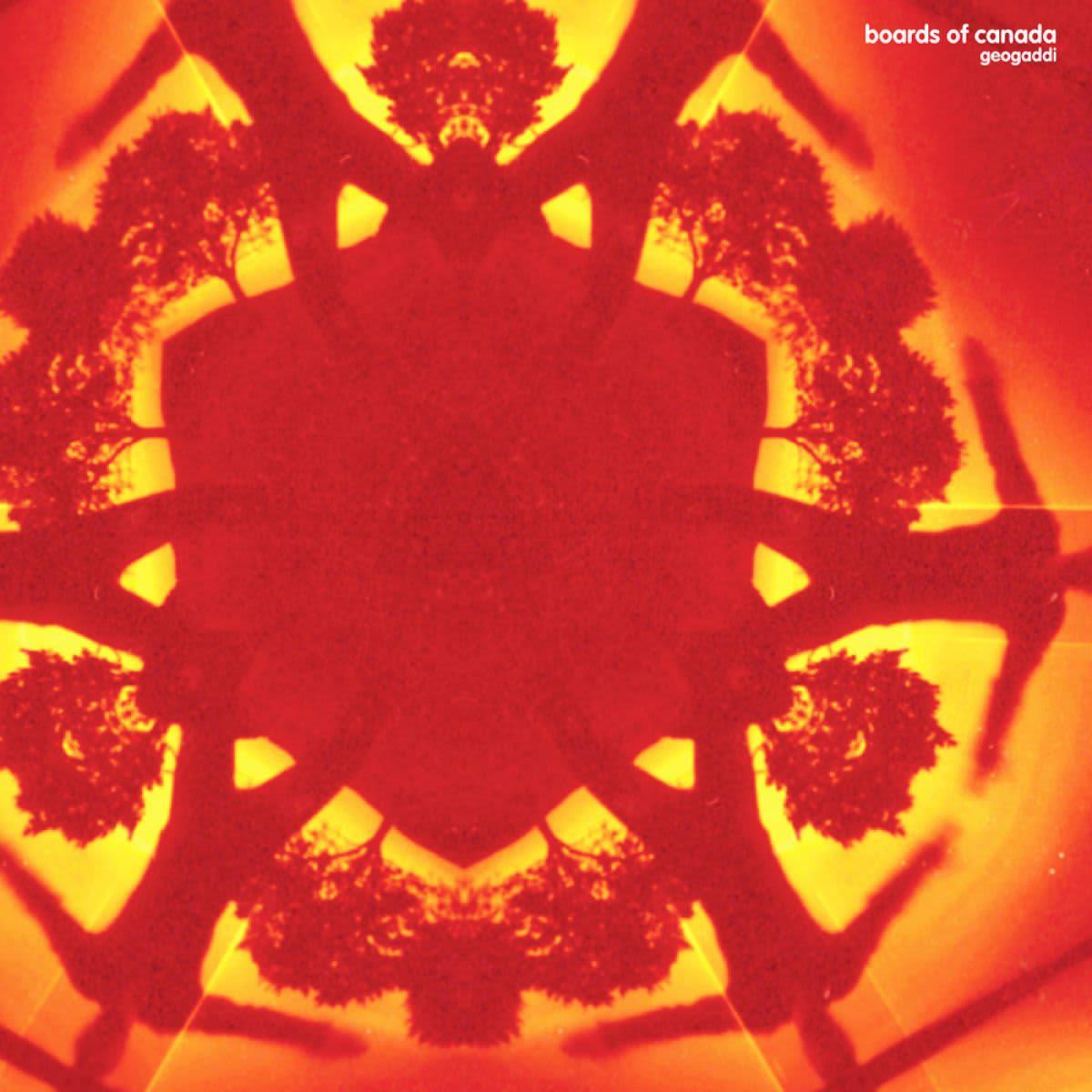

While I can’t see into the future and determine what public musical memory will look like in twenty years (or if it will exist at all in any sizable capacity), I can already see the shifting role of existing music that is considered to evoke hauntology. Without realizing it at least ten years ago, if not longer, I was first introduced to Boards of Canada through the Salad Fingers YouTube series by David Firth, which began in 2007. Throughout the series, “Beware the Friendly Stranger” from Boards of Canada’s Geogaddi (2002) acts as the unsettling score to the bizarre, surreal animated series. Geogaddi continued their tradition of warping samples of children’s television programming, nature documentaries, and even number stations, its hauntology discussed in fantastic detail in this article by Adam Harper. Within five years of Geogaddi‘s release, shifting media consumption practices through YouTube would begin gathering more layers to Boards of Canada’s commentary on media and memories.

In the comments section for “Beware the Friendly Stranger” on YouTube, some of the comments address typical feelings associated with Boards of Canada: “The feeling I get when listening to this is unexplainable”; “This music is strangely, eerily nostalgic”; “this has that weird forgotten feel to it, where you find it playing on a recorder in some odd house.” Other comments connect the song back to Salad Fingers: “This track haunted me ever since I first watched Salad Fingers back in the day”; “I just recently discovered Board[s] of Canada and I was not prepared to find out where the salad fingers music came from”; “While listening to this I expect to hear Salad fingers say hello,” along with many quotes from the series.

In my personal experience, “Beware the Friendly Stranger” always evokes early YouTube instead of early television, adding an intermediary layer between the present and the distant past. The famous quote from Geogaddi’s “Music is Math,” “The past inside the present,” is twisted in this instance. The meanings we have in the present are changing the interpretation of a past musical work. While this phenomenon is certainly not unique to this example or hauntology, it shows how the nature of the Internet and social media crafts a changing society. Whereas “Beware the Friendly Stranger” used to evoke public musical memory, it’s now emblematic of a popular, yet incredibly specific, corner of YouTube. Will YouTube then be the next hauntological source? Or is it too splintered in its identity to speak to a widespread, unified experience?

This blog post has no answers I’m afraid, simply a lot of questions. But they are questions that have arisen in response to many concrete changes I’ve noticed in communication and mass media in recent years. If you’ve wondered similar things, or have something to say about this topic in general, feel free to email me at hannahrachelmusic05@gmail.com. There is so much to say and speculate about hauntology, mass media, and memory that goes beyond the space I have here, and the knowledge I currently possess. So if you want to drop me a line, I’d love to have some conversations about it all.

– Hannah Blanchette

July 2, 2023 | Blog