Subtotal: $20.00

The Internet, Micro-Communities, and the Future of Interdisciplinary Art

The other day, I was waiting for a friend to meet me at a coffee shop when I decided to pass the time with a Wire article or two. In the table of contents for their 2024 Rewind issue, an article about Black Rain jumped out at me, the subtitle reading, “Neo-Neuromancer.” Earlier this year, I read William Gibson’s seminal cyberpunk novel, Neuromancer, and I was curious about this reference appearing in the magazine. Written by Phil Freeman, the piece is an excellent feature on the electronic duo Black Rain, whose members collaborated with Gibson numerous times throughout their lives, notably to record an audiobook soundtrack for Neuromancer in 1994. I finished that piece and moved on to another, the avant-garde composer Pamela Z on the Robert Rauschenberg, Talking Heads cover. She wrote, “I was drawn to artists – like David Byrne, Brian Eno, Laurie Anderson and John Cale – who were working interdisciplinarily or collaborating across boundaries with visual artists, choreographers, film makers and experimental theatre directors…I was jumping in with both feet to join a newly discovered world of artists with avant garde leanings who were combining disparate elements to make more adventurous work.”

As I was reading these pieces, I started to think further about how vibrantly interdisciplinary art was in the late-twentieth century. Musicians, authors, filmmakers, and artists seemed to be rubbing elbows at every corner, inspiring and collaborating with one another as if it were inherent, was required of them to do so as creative people. My first thought was that this happened because they literally were rubbing elbows, they were existing together in localized art scenes that facilitated frequent contact and forums for conversation. I wouldn’t be saying anything new to suggest that the Internet eroded the sense of localized art community to some degree, and while I am kind of saying that, I want to dive deeper into that concept. As time progresses, will varying art scenes that otherwise would collaborate in interdisciplinary art isolate themselves more and more through specified communities on the Internet? I consider this piece an installment of an initially unintentional series, connected to my previous post on streaming and data, and I have another idea in the queue that will also touch upon the intersection of our modern music industry and technology. Quite frankly, this is very much where my brain is at as the year comes to a close and I reflect on how the technological progress of the past twelve months has shaped and will continue to mold music going forward. I hope you’re enjoying this journey with me.

The Internet has developed reflecting humanity’s penchant for categorizing things. What is found on the Internet, especially on social media, can be shuffled off into hashtags, subreddits, groups, and servers, each with the particular function of tailoring your experience online to exactly what you would like to see. This functionality then bleeds into how information is conveyed on the Internet, lightly reminding me of Marshall McLuhan’s “The Medium is the Message.” “Book Tok” has a tendency to condense the content of books into easily identifiable tropes that fit with hashtags and be conveyed in a short span of time via TikTok video. Micro-aesthetics develop that dictate an exact fashion or decorative style, everything becoming a “_______core” (although this -core tendency isn’t exactly new, look at all the subgenres of punk music that have cropped up over decades). Tiny micro-communities reflecting what you love emerge, whether you purposefully seek them out or not. To some degree, these communities are valuable, allowing those on the margins to find a voice and a support network.

While I cannot assume how much, or how little, the current avant-garde and underground art scenes are engaging with spaces such as Book Tok and cottagecore, these trends regardless shape the way these online spaces function, even for interests found on the margins. Theoretically, if the algorithm is only displaying exactly what you’re already interested in, say experimental music, will it show you experimental film? Experimental fiction? Or will it keep showing you more experimental music? Many, if not most, of creative people these days are engaging with online spaces in some way, contributing something only then to consume something, on and on the cycle goes. Months ago, I also read Jennifer Egan’s The Candy House, a novel set in a version of society which has the technology to download one’s unconscious memories for later viewing. This innovation led to the Collective Consciousness, where one can view others’ memories, but only if they upload their own. The Internet and social media function in similar ways. You are expected to produce something for an online space if you wish to also take from it. The more you produce and take, the more a certain website understands your specific tastes and whittles your online world into an echo chamber of you. As I stated earlier, many of us already have a predisposition to categorize things on our own accord — even the separation of music, art, film, theatre, and literature into distinct spaces reflects that concept. What happens when online spaces start to do that work for us? As we center our lives more and more online, will we lose touch with the ways different types of art flow into, overlap, and connect with one another?

Maybe I am sounding the alarm too soon, or maybe an alarm doesn’t need to be sounded off at all. Just as much as we have historically loved to categorize and create subgenre after subgenre, humans also seek one another out, and creative people will find one another to innovate. But I believe than anyone who creates engages with creative work needs to remain vigilant and strike a balance between their online realm and the concrete creative spaces in their surroundings. In my opinion, one space that has been doing the work to encourage interdisciplinarity in art and expand the palettes of local creatives is Covington, Kentucky’s Conveyor Belt Books. From hosting music events in their bookstore to putting on film screenings and art exhibitions around town, they demonstrate the inherent interconnected nature of art that an algorithm cannot destroy.

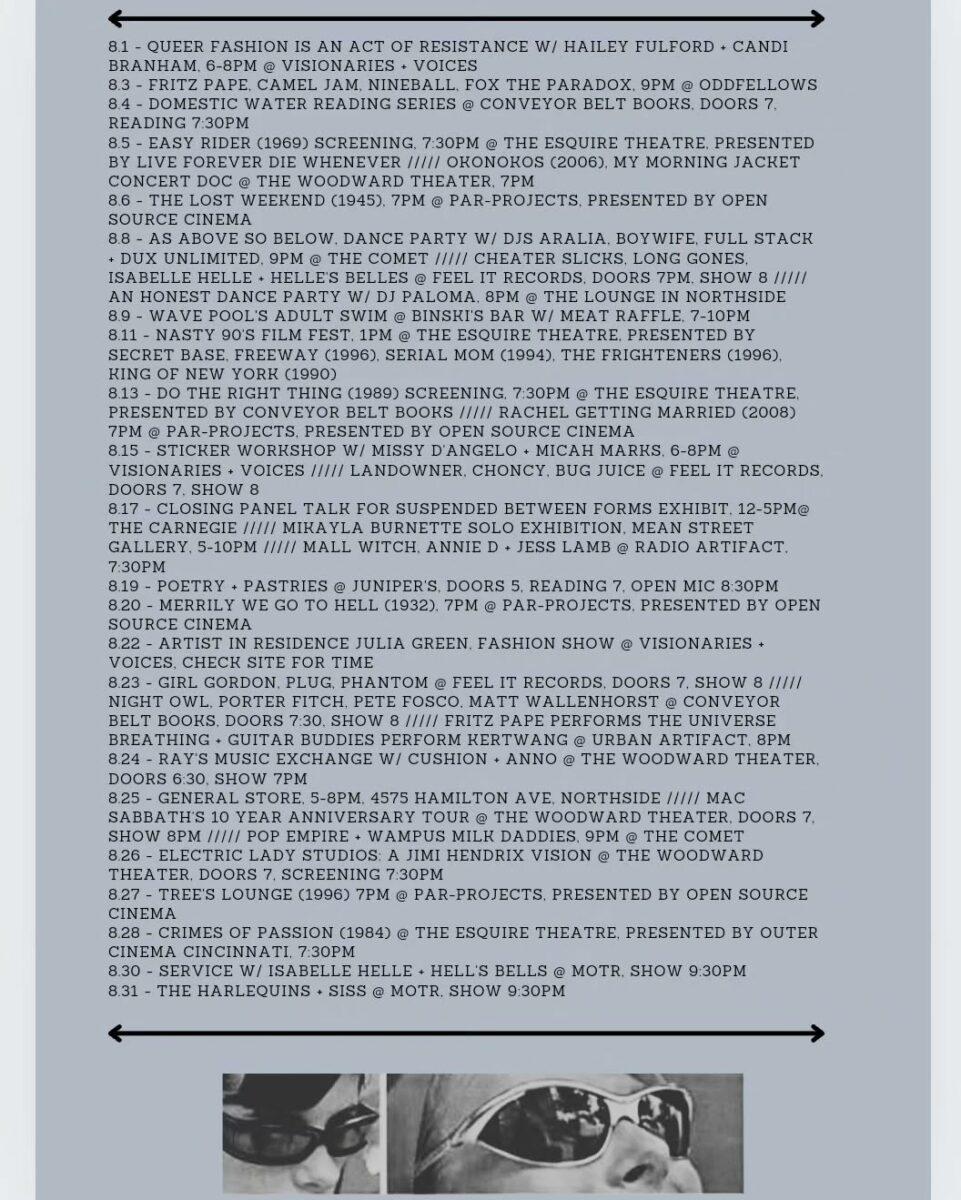

A few months ago, Conveyor Belt began a print series called “An Object at Rest Remains So Unless,” a monthly paper calendar of events happening in the area that reflect all sorts of art, to be distributed as mini flyers throughout the city. The initial social media post about the initiative (ironic, I know, but again this is the world we live in) read, “The guiding idea has been motivated by countless conversations over the past year with folks about the dissemination of info regarding gigs, screenings, exhibits & various goings-on in town. A lot of this stuff can get lost in the ruthless insta algorithms, which are more likely to show you an ad for the millionth pilates place to open in Fresno or whatever than something interesting/cool happening in your nearer solar system.”

Algorithms are cushy and comfortable, they guide you through a realm that is exactly your own. But artistic experimentation, transgression, and innovation are not comfortable, and in theory should not be amenable to the algorithm. “Collaborating across boundaries” in art like Pamela Z discussed in her article should be so undefinable that hashtags cannot explain it. Step outside the four walls of the phone brick in your hand and, as Conveyor Belt says, experience something unexpected and transcendent in “your nearer solar system.”

– Hannah Blanchette

December 17, 2024 | Blog

Steve Underwood “Even When It Makes No Sense - the Broken Flag Story”

Steve Underwood “Even When It Makes No Sense - the Broken Flag Story”