-

×

Penguin Cafe - Handfuls Of Night

1 × $10.00

Penguin Cafe - Handfuls Of Night

1 × $10.00

Subtotal: $10.00

In 2023, Cincinnati-based musician and recording engineer Isaac Karns released Infinite Directions, a set of cards to “stimulate your creative process.” Featured on the cover of Tape Op magazine and already receiving tons of positive feedback, Infinite Directions is a fresh approach to artistic creation that aligns with a robust history of experimental compositional tools. I spoke with Karns in December about the inspiration behind Infinite Directions, the choices that went into its design, its relationship to indeterminate musical processes, and the success the cards have found within their first year of release.

Isaac Karns was born in Hamilton, Ohio, and moved to Cincinnati when he was eighteen-years-old. In his early twenties, he joined a band called Pomegranates, immersing himself in the 2000s indie rock scene. He found an affinity for the recording process, enjoying the tinkering that goes into making a record. Self-taught, Karns began to work in studio spaces gaining recording experience, eventually opening a studio with the drummer from Pomegranates. Now, Karns has run The Marble Garden recording studio for nearly ten years, working with artists such as Tough Friend, Bailey Miller, Animal Mother, ZOO, Sylmar, FLOCKS, and Moonbeau.

The first seeds of Infinite Directions appeared when Karns became involved in the world of music licensing as a contract composer with a library music company based in Nashville, Tennessee. Over the span of two and a half years with them, Karns was tasked with submitting six songs a month to their library, composing around 170 tracks total during that time. Due to the recurrent time constraints of this work, Karns had to confront what he deemed, “the evergreen dilemma of the empty page.” While writing music can seem like a carefree, when-the-muse-strikes process, it often has to be crafted into a discipline to adhere to the expectations of others. Karns no longer believes in writer’s block, instead ascribing to the philosophy of Pablo Picasso when he said, “Inspiration exists, but it has to find you working.” Through composing library music, Karns couldn’t wait for inspiration, instead he had to manifest it himself.

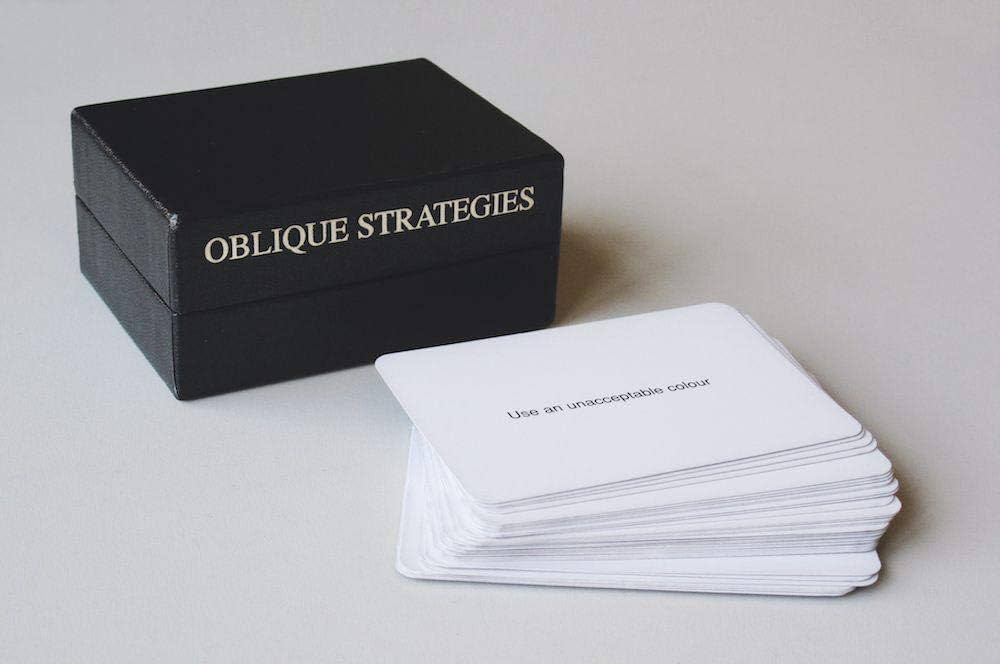

To summon ideas, Karns tried using samples and setting parameters for his process. The most influential and effective implement he found was Brian Eno and Peter Schmidts’ Oblique Strategies cards. First published in 1975, Eno and Schmidts’ cards featured esoteric phrases for jump starting the creative process. Eno brought them into sessions with artists he worked with such as David Bowie, Talking Heads, and Devo, not always to rousing success from the musicians. Similarly, Karns brought the cards, printed off from a bootleg PDF at the time, into sessions with artists in the studio as well. In true fashion, one musician became annoyed when tasked with a card which reads, “Honor thy error as a hidden intention.” But despite that, he came up with an idea as a result that everyone in the group loved. The ingenuity of these cards, as well as Infinite Directions, lie in how the same prompt can produce different results from different people, allowing for an endless expanse of permutations and possibilities. The cards also help an artist see their craft as if it is their first time creating again, opening up the mind outside of the routine, characteristic choices they would normally make.

Karns wanted to create his own set of cards that were more concrete than Eno’s vague, abstract phrases. The last piece of inspiration that sparked the Infinite Directions project was a video installation that Karns saw at Cincinnati’s BLINK Festival in 2018. The installation was comprised of multiple screens displaying a piece of paper with words that would then get crumpled and changed, creating various sentences in a style like an exquisite corpse. Seeing this concept laid the groundwork for the modular structure of Karns’ own Infinite Directions, which he then developed over the next three years.

Karns created the design and layout for the cards himself, consistently seeking feedback from his friends and collaborators. The words and phrases on the Infinite Directions set range from words with strong musical connotations, such as “percussion” and “loops,” to others which are more open-ended like “shiny” and “watery.” Karns brainstormed the words for the cards in a large spreadsheet, wanting terms that were very evocative and concrete, as well as more intuitive. Drawing the cards from the deck would be “like tarot for your creative process,” Karns said.

For the visual design of the set, Karns sought an organic, handmade feel. He was specifically drawn to how artists such as Keith Haring and Howard Finster made art with few materials, and not always the best tools. Karns took this sentiment to heart, keeping as his internal mantra, “Do your best with what you have here and now.” He always advises other artists that their most important tool is their mind, and that you don’t always need the best piece of gear to make something compelling. Karns even paid tribute to Finster with a font for the set in a Finster-inspired typeface. The shapes and colors on the cards create a sense of sequence, such as 1–2–3, without using numerals. Each of the shapes and colors adhere to different types of prompts, allowing the artist to “filter” their experience using the cards. For example, one can choose to remove the color blue entirely from the deck during use, changing the results in the process.

While Oblique Strategies was the primary historical inspiration for Infinite Directions, Karns acknowledges a lineage that goes back further than Eno, excited to be in dialogue with previous methods. Some have noted a similarity between Infinite Directions and John Zorn’s Cobra system, which involved a set of cards with cues, and corresponding rules to direct a musician how to respond to the cues in performance. Using methods like these certainly calls to mind the indeterminate musical processes of avant-garde figures such as John Cage and La Monte Young. Karns has been a fan of Terry Riley’s since high school, a time when the weirder the music was to him, the better. Along with the aforementioned musicians, he also loved Iannis Xenakis, Milton Babbitt, and Morton Subotnick. Terry Riley remained a particular favorite, and Karns even reached out to Terry Riley’s manager and sent the composer an Infinite Directions set in gratitude for his inspiration.

The initial audience that Karns assumed would gravitate towards Infinite Directions were experimental musicians. Since their release, he has heard back from many kinds of creatives that he didn’t expect would be drawn to the cards. One of the most frequent groups he’s received feedback from are music educators, especially those who teach private lessons. They have stated that Infinite Directions helps their students approach making music in a different way, allowing them to apply the tools they’re learning to a musical process. Karns himself has taught some of the Infinite Directions techniques at a music camp for ages six through twelve, finding similar success. Professors at universities have also been interested in the cards, and outside of music, visual artists have used Infinite Directions in their creative processes.

Going forward, Karns is interested in making expansion packs for Infinite Directions, perhaps using color gradients instead of words and creating packs intended for live performance and improvisation. The cards are already starting to be used in that way, such as the above improvised piece by the Cincinnati-based jazz octet Tough Friend. Each member drew a card and then performed based on its direction, live in one take. Steering Infinite Directions towards this focus could certainly shift the meaning of what a compositional tool like Infinite Directions is — can the process be the music itself? Ultimately, the decision will come down to the artist holding the cards in their hand, which definitely makes the possibilities limitless.

– Hannah Blanchette

January 5, 2024 | Blog