Paying Attention to Library Music

For a while now, I’ve had a fascination with music you’re expected to ignore, i.e. Muzak, easy listening, and stock music. It began when I read this fascinating article from 1997 by sound studies scholar, Jonathan Sterne, “Sounds like the Mall of America: Programmed Music and the Architectonics of Commercial Space.” The article discussed how music is used in commercial spaces, such as malls, to create the flow and sense of space to the point that it is just as critical as the architecture. I was intrigued by – and even slightly disturbed by – the concept of music having such a subliminal impact on aspects of daily life, especially in consumer spaces.

For a while now, I’ve had a fascination with music you’re expected to ignore, i.e. Muzak, easy listening, and stock music. It began when I read this fascinating article from 1997 by sound studies scholar, Jonathan Sterne, “Sounds like the Mall of America: Programmed Music and the Architectonics of Commercial Space.” The article discussed how music is used in commercial spaces, such as malls, to create the flow and sense of space to the point that it is just as critical as the architecture. I was intrigued by – and even slightly disturbed by – the concept of music having such a subliminal impact on aspects of daily life, especially in consumer spaces.

This interest of mine extends to library music, also known as stock music or production music, the music of public broadcast documentaries and low-budget horror. As Nate Patrin said in Pitchfork, “Library music gives us a picture of the way day-to-day music sounded like decades ago.” Just as Muzak provided the musical architecture of commercial space, library music was the music of 1am television, the radio in the kitchen, the TV cart in an elementary school classroom.

Library music is music prepared for film, television, and radio that can be borrowed by creators at a lower cost than having an original score composed. The musicians behind library music work for hire and are frequently unknown by those who use the music. Sometimes the composers even work under various pseudonyms. Instead, the music is more affiliated with a certain music library, such as the British KPM or Italian CAM libraries. Library music began with 78-rpm records included on live radio broadcasts, before growing in popularity with the rise of television in the sixties and seventies. Using library music became particularly popular in certain genres of film and television, especially science fiction, horror, blaxploitation, porn, news, sports, and educational films.

Because of the diverse array of genres that used library music, the music itself was also varied. Generally, the musical styles of sixties and seventies library music included cues in the style of the Top 40 hits of the time, easy listening akin to work by Henry Mancini, and avant-garde electronics. Composers were also sometimes tasked with creating “knock-off” versions of popular songs to use in low-budget films and television, writing a famous tune with a few notes changed so that it could be included without needing to pay for the real song.

Because of the diverse array of genres that used library music, the music itself was also varied. Generally, the musical styles of sixties and seventies library music included cues in the style of the Top 40 hits of the time, easy listening akin to work by Henry Mancini, and avant-garde electronics. Composers were also sometimes tasked with creating “knock-off” versions of popular songs to use in low-budget films and television, writing a famous tune with a few notes changed so that it could be included without needing to pay for the real song.

Overall however, library music does not invoke a particular genre or sound, rather, emphasis is placed on depicting a mood or narrative, although even the moods and narratives illustrated are widespread. Famed library music composer Alan Hawkshaw described the process as: “With a library piece, you’ve only got a blank piece of paper. And possibly a title: ‘Wildlife,’ ‘Corporate,’ ‘Drama.’ You’ve got that, and you start from there. You’ve got nothing to get you started except your own mind.” Another library music legend, Keith Mansfield, discussed this process while emphasizing how library music was meant to blend into the background unnoticed: “…One of the things is to try and maintain a mood, but somehow make it interesting, without being too interesting, because it’s if it’s too interesting, suddenly you’re aware of it. And what you’re trying to do is for people not to be aware of it.”

Throughout the years, many library records have been ignored and disposed of. While originally composed scores for film and television garner a certain level of respect and attention, to the point that they are increasingly performed in concert halls and given meticulously crafted vinyl reissues, library music has a reputation of being considered more banal, generic, and inconsequential. However, as David Hollander asserts in his book, Unusual Sounds: The Hidden History of Library Music, this is often not the case. He writes, “Without the pressure to generate ‘hits,’ young library composers were free to play around and experiment, and they took full advantage. The need for speed in production contributed to the ethos of spontaneous creativity.”

The output of the BBC Radiophonic Workshop was a prime example of how library music could be a site of experimentation and creativity. The Workshop was founded in 1958 as a place to create sound effects and stock music for BBC programs, resulting in groundbreaking advances in electronic sound and music. Delia Derbyshire was an integral member of the Workshop and her arrangement of the Doctor Who theme helped elevate the tune composed by Ron Grainer to an otherworldly level. At this time, technical assistants to composers were not given credit for their work, and despite Grainer wanting Derbyshire to have co-composition credits for the Doctor Who theme, her contributions to the theme went unrecognized for a long time. Other compositions of Derbyshire’s used in Doctor Who also appeared in documentaries, such as “Blue Veils and Golden Sands” which was included in a documentary about the Taureg people of the Saharan region of Africa. “Blue Veils” is a prime example of library music’s experimental slant, with a musique concrète approach of oscillating the sound of hitting a metal lampshade.

The output of the BBC Radiophonic Workshop was a prime example of how library music could be a site of experimentation and creativity. The Workshop was founded in 1958 as a place to create sound effects and stock music for BBC programs, resulting in groundbreaking advances in electronic sound and music. Delia Derbyshire was an integral member of the Workshop and her arrangement of the Doctor Who theme helped elevate the tune composed by Ron Grainer to an otherworldly level. At this time, technical assistants to composers were not given credit for their work, and despite Grainer wanting Derbyshire to have co-composition credits for the Doctor Who theme, her contributions to the theme went unrecognized for a long time. Other compositions of Derbyshire’s used in Doctor Who also appeared in documentaries, such as “Blue Veils and Golden Sands” which was included in a documentary about the Taureg people of the Saharan region of Africa. “Blue Veils” is a prime example of library music’s experimental slant, with a musique concrète approach of oscillating the sound of hitting a metal lampshade.

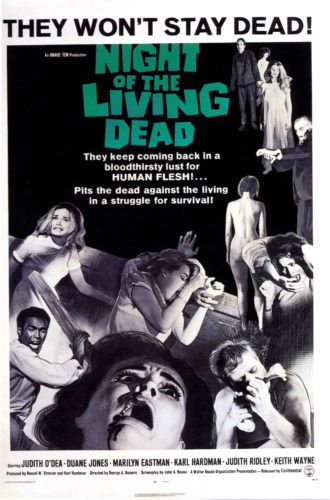

One of the most well-known uses of library music in cinema was for scoring George A. Romero’s 1968 cult horror classic, Night of the Living Dead, so notable that Romero even provided the preface to Hollander’s Unusual Sounds. Romero described his experience of selecting music for Night of the Living Dead in this preface:

One of the most well-known uses of library music in cinema was for scoring George A. Romero’s 1968 cult horror classic, Night of the Living Dead, so notable that Romero even provided the preface to Hollander’s Unusual Sounds. Romero described his experience of selecting music for Night of the Living Dead in this preface:

“When I made my first film, Night of the Living Dead, in 1968, I found myself with barely enough of a budget to complete the project, let alone hire a composer. The finished film played… mmm, pretty well, but something was missing. It needed music. Several friends of mine and myself had a small production company at the time, the Latent Image, which was surviving on beer commercials, industrial films, and the like. In order to make Night of the Living Dead, we partnered up with an audio production company, Hardman and Associates…As it turned out, Karl’s audio company had hundreds…I might say thousands (it seemed like thousands)…of records, vinyl discs that contained countless hours of music. None of it was specific to any film, but there were passages titled ‘Anticipation,’ ‘Suspense,’ ‘Sudden Shock.’…All of a sudden, Night of the Living Dead inherited a score.”

Romero would take the audio samples back to the editing studio and test them out against scenes until he found the perfect choices. The end result was a suspenseful, cohesive score put together by library music cues from multiple composers: Spencer Moore (heard above), William Loose, George Hormel, Ib Glindemann, and Philip Green. As the film grew its cult following, the score gained a following along with it, to the point where the cues used in the soundtrack lost the anonymity commonly attached to specific library music tracks. The soundtrack became so popular that Varèse Sarabande eventually released an official soundtrack in 1982, which was highly unusual for library music.

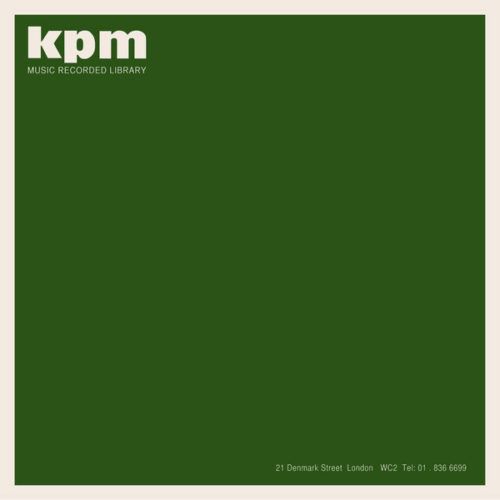

While Night of the Living Dead might be the most iconic film with a library music score, the most well-known music library itself is KPM, specifically its KPM 1000 series. KPM began as a musical instrument shop in the 1700s, before also offering sheet music in the early 1800s. With the advent of recorded sound in the early twentieth century, the music publishing division became its own company by 1955, KPM. The KPM 1000 series are now iconic library recordings, characterized by their plain, green sleeves. Two of the most celebrated composers who wrote for KPM were Keith Mansfield and Alan Hawkshaw. Mansfield’s style is funk-tinged pop instrumental tunes, used especially in British sports media, including Wimbledon broadcasts, Grandstand, and The Big Match. Two of the records we have of his, Contempo and Vivid Underscore exemplify his typical style – upbeat, orchestral tracks with funk bass and guitar, which definitely evoke a seventies shopping center (the track “Breezin’” feels especially luxurious).

While Night of the Living Dead might be the most iconic film with a library music score, the most well-known music library itself is KPM, specifically its KPM 1000 series. KPM began as a musical instrument shop in the 1700s, before also offering sheet music in the early 1800s. With the advent of recorded sound in the early twentieth century, the music publishing division became its own company by 1955, KPM. The KPM 1000 series are now iconic library recordings, characterized by their plain, green sleeves. Two of the most celebrated composers who wrote for KPM were Keith Mansfield and Alan Hawkshaw. Mansfield’s style is funk-tinged pop instrumental tunes, used especially in British sports media, including Wimbledon broadcasts, Grandstand, and The Big Match. Two of the records we have of his, Contempo and Vivid Underscore exemplify his typical style – upbeat, orchestral tracks with funk bass and guitar, which definitely evoke a seventies shopping center (the track “Breezin’” feels especially luxurious).

Alan Hawkshaw is most well-known for his distinctive Hammond organ sound and the track, “The Champ,” which has gone down in history as one of the most sampled tracks in hip-hop (in 748 songs, according to WhoSampled), its breakbeat iconic of early Bronx hip-hop. The first song that came to mind for me that samples it is Salt-N-Pepa’s “Tramp,” which clearly includes pitch-adjusted samples from “The Champ.” However, some of my personal favorite material from Alan Hawkshaw is his synthesizer works, such as the track “Crystal Vision” from Bruton’s release, Kinetics/Vision, which is utterly transcendent ambient synth music.

In my opinion, the British music library Bruton Music produced some of the most brilliantly designed library music album covers, which as it turns out was part of the point. Bruton Music was founded by former KPM figure Robin Phillips, who “ensured that Bruton stood out from his former library through its eye-catching, often bizarre record sleeves, a far cry from the standardized ‘greensleeves’ used for the KPM 1000 series.” Bruton covers have a uniform layout – the library logo in the right corner, the name of the record in the top left – but unique designs and photography on each release. The colors were bold and bright and the designs minimalist, easily conveying the theme of the record (such as Underworld’s cover photograph of a snarling eel, which I think is appropriate). Although I understand the utilitarian nature of the KPM 1000 “greensleeves,” I think the Bruton covers were a step in the direction of elevating library music from simply its function to being considered art in its own right.

In my opinion, the British music library Bruton Music produced some of the most brilliantly designed library music album covers, which as it turns out was part of the point. Bruton Music was founded by former KPM figure Robin Phillips, who “ensured that Bruton stood out from his former library through its eye-catching, often bizarre record sleeves, a far cry from the standardized ‘greensleeves’ used for the KPM 1000 series.” Bruton covers have a uniform layout – the library logo in the right corner, the name of the record in the top left – but unique designs and photography on each release. The colors were bold and bright and the designs minimalist, easily conveying the theme of the record (such as Underworld’s cover photograph of a snarling eel, which I think is appropriate). Although I understand the utilitarian nature of the KPM 1000 “greensleeves,” I think the Bruton covers were a step in the direction of elevating library music from simply its function to being considered art in its own right.

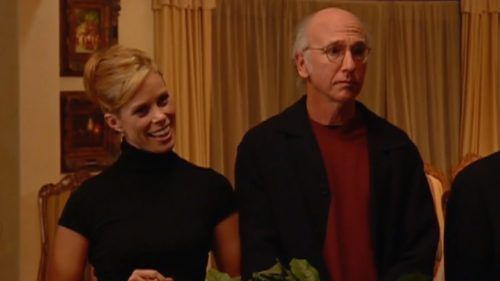

Although library music is still consistently created today, relics of the past still reappear and find new purpose in the twenty-first century. One notable example is Larry David’s comedy series Curb Your Enthusiasm, whose now iconic theme song and incidental music are intimately tied to the series, and accompany jokes and memes across the Internet. The Curb theme is a piece of library music from 1974 titled “Frolic” by Italian composer Luciano Michelini, sourced from the current library Killer Tracks. Another identifiable cue included in Curb is by Franco Micalizzi, “Amusement,” which frequently accompanies transitional sequences such as driving or walking around. The bright, upbeat nature of these tracks serve as the perfect counterpoint to Curb’s comedy, which is often irreverent and uncomfortable, providing both moments of cognitive dissonance and comic relief.

Although library music is still consistently created today, relics of the past still reappear and find new purpose in the twenty-first century. One notable example is Larry David’s comedy series Curb Your Enthusiasm, whose now iconic theme song and incidental music are intimately tied to the series, and accompany jokes and memes across the Internet. The Curb theme is a piece of library music from 1974 titled “Frolic” by Italian composer Luciano Michelini, sourced from the current library Killer Tracks. Another identifiable cue included in Curb is by Franco Micalizzi, “Amusement,” which frequently accompanies transitional sequences such as driving or walking around. The bright, upbeat nature of these tracks serve as the perfect counterpoint to Curb’s comedy, which is often irreverent and uncomfortable, providing both moments of cognitive dissonance and comic relief.

The influence of library music can be seen in a lot of rock and electronic music of the past twenty to thirty years as well. The legacy of library music can be heard in electronic artists like Boards of Canada, whose music samples public television documentaries and children’s programs, and uses vintage synthesizers, commenting on nostalgia through a sonic landscape evocative of outdated visual media. Traces of library music cover design can be seen in the artwork of Stereolab records and the album art of Robert Beatty. Even the Torn Light release by Flanger Magazine, Breslin, draws upon the inspiration of library music, described by Keith Fullerton Whitman as “A set of spry, pastoral Acoustic Guitar and errant Electronic pieces that harken back to libraries by Teisco, Vittorio Marino, and the like, yet mapped in an alien manner unlike any known lanes.”

Library music’s influence and appeal to this day brings me to my final thoughts. I’d say it’s rare to find anyone who’d want to listen to current library music, however the music from the sixties, seventies, and eighties carry a certain magic – as Pitchfork described, it’s “a little bit mysterious and dusty.” The records are often incredibly rare, yet undervalued, and the music offers glimpses into once commonplace styles of music that have since died off. Like Muzak, library music was once everywhere, ignored or despised on a regular basis, and now only remains as haunting reminders of what the past sounded like. With the rise of extreme personalization on digital media and online shopping, commonly heard music via public broadcasts and public space is shrinking, making twentieth-century library music more of a novelty. I think the nostalgia towards library music is partly a nostalgia for this pre-digital way of being. Will there be functional music from today that garners this same level of nostalgia in forty or fifty years? Only time will tell, but that landscape will certainly be affected by how we consume functional music now.

Resources

I highly recommend checking out David Hollander’s book, which has incredible interviews and a huge collection of library music artwork and scans of paraphernalia. Also, this YouTube playlist of seventies and eighties synth library music is a favorite of mine.

Robert Barry, “Cinema Without Images: The Unusual Sounds Of Library Music,” The Quietus (2018)

“Delia Derbyshire – Doctor Who Theme (Original Theme by Ron Grainer),” BBC

Conor Herbert, “Library Music Is Changing the Sampling Game In Hip-Hop,” DJ Booth (2019)

David Hollander, Unusual Sounds: The Hidden History of Library Music (2018)

Rob LeDonne, “‘Curb Your Enthusiasm’ Music Supervisor Explains the Strange History of the Show’s Iconic Theme,” Billboard (2017)

Peter Lucas, “Unusual Sounds: The Hidden Histories of Library Music,” Glasstire (2018)

Nate Patrin, “The Strange World of Library Music,” Pitchfork (2014)

Will Pritchard, “Unusual Sounds: How Library Music Became the Final Frontier for Record Collectors,” The Vinyl Factory (2018)

In the Shop

Sammy Burdson – Background Action (Conroy)

Daniela Casa – Ricordi D’Infanzia

Jean-Pierre Decerf – Space Oddities 1975-1979

Bernard Estardy – Fragments D’une Empreinte Magnétique

Gerardo Iacoucci – La Avventure

I Marc 4 – Thrilling Mortale

Riccardo A. Luciani – Inchiesta Sul Mondo

Keith Mansfield – Contempo (KPM)

Keith Mansfield – Vivid Underscore (KPM)

Nino Nardini – Musique Pour Le Futur

H. Tical – Impact Synthesized Sound And Music

Amedeo Tommasi – Zodiac

Klaus Weiss Rhythm And Sounds – Sound Inventions

V/A – Mare Romantico

V/A – New Tape

V/A – Underground Mood

Check out more in our soundtracks & library music section!

– Hannah Blanchette

June 26, 2022 | Blog