Subtotal: $10.00

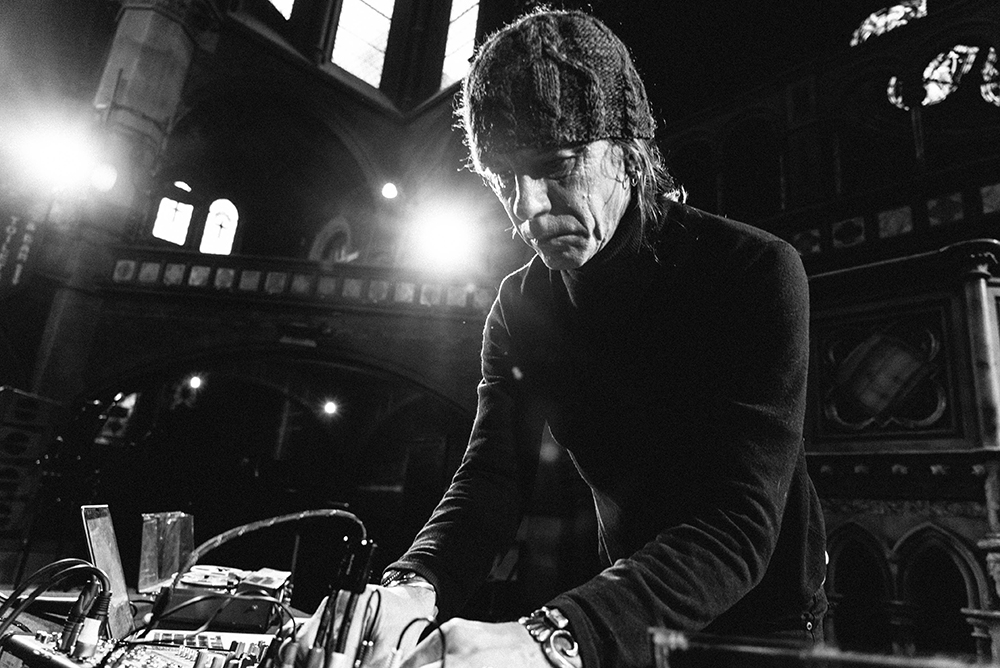

No Expiration Date: William Basinski, Background Music, and a World Without Decay

Ahead of William Basinski’s upcoming archival release, September 23rd, I started thinking in the opposite direction of what I wrote about a few weeks ago with John Cage, ultimately writing a sister piece to my last one. In discussing Cage’s Organ2/ASLSP, I reflected on the radical nature of a performance lasting for centuries, embracing the delirious longevity of one work of art in a fast-paced society. This week, Basinski has me reflecting on the importance of decay that he quite literally depicts in his music. Perhaps best exemplified in his work, The Disintegration Loops — an ambient landmark that catches real-time tape degradation of slowed-down slices of muzak — Basinski’s work has consistently existed to remind us that entropy is real, and the real does not last forever.

In creating The Disintegration Loops, Basinski embraced muzak, a popular brand of generic background music in mid-century America that was synonymous with elevator music. I’ve also sustained a fascination with muzak, along with other forms of background music such as library music, and Basinski has contemporaries in artists such as Stereolab who experiment with easy listening genres. Basinski stated that muzak “was like anaesthesia music. Before Prozac there was muzak. But when you slowed it down, like looking into a microscope, there’s this huge well of melancholy there.”

When I consider what the contemporary equivalent of muzak could be, I often think of the well-known “lofi hip hop radio beats to relax/study to” livestream on YouTube, which according to the video, started streaming a little over two years ago on July 22, 2022. The video provides nondescript, unobtrusive music for background use in a similar fashion to muzak, although I do believe muzak had a more public-facing component that is not paralleled in “lofi hip hop radio beats.” This example is one of, I would estimate, thousands of similar videos each providing live or hours-long compilations of background music spanning genres. [Sidebar: I have authentically been writing a lot of this text with “lofi hip hop radio beats” on in the background, and I can attest to the fact it is very ignorable, and therefore also very effective for writing.]

Considering Basinski’s experiment with The Disintegration Loops, what’s interesting about “lofi hip hop radio beats” compared to muzak is that there is no room for degradation within the former. Without interference, that video can continue playing seamlessly and flawlessly, theoretically forever. Where is the entropy? Basinski exposed muzak’s weakness: that while in its prime, muzak could play on and on unobtrusively for hours and hours, time would eventually take its toll. Once the tapes started disintegrating, which happened more with each play, the muzak was no longer ignorable. Its decay made it beautiful, transformed it into something worth listening to. Each little hiccup, every stutter from the tapes tugs on your heart as you consider the gasping breaths of this music fighting its way out for what was likely the last time. So what is lost when this risk is taken away? What do we sacrifice when the soundscapes produced by the digital world have no expiration date?

Devotees of physical media, who I would assume make up a large portion of the people reading this blog, understand these questions better than anything. We know objectively that our vinyl will scratch, our tapes will break down, and even our CDs can wither on the floors of our front carseats. With each play, we bring them closer to their demise. And on the flip side we denounce, or at best tolerate, streaming with its smoothed edges and seeming infallibility. However, we also know this binary is more complex than this. Despite physical media’s flaws, I feel as if my records will last forever. I imagine grabbing the same Sonic Youth tape off my shelf when I’m fifty, sixty, seventy, as I do now, even though I recognize that the tape itself is already over thirty years old.

Too often, we are also ruthlessly reminded of how imperfect and impermanent streaming is. Versions change, albums are removed, and your “collection” could disappear in the blink of an eye if Spotify wanted it to. At first glance, Basinski’s rumination on decay through his compositions seems counter to the sleek experience of digital media. I mean, if you listen to The Disintegration Loops on Spotify, the record will never disintegrate itself. If you grab a copy on vinyl, your version will gradually fall apart along with the music itself. Each physical copy of The Disintegration Loops embarks on its own journey of decay, creating layers upon layers of degradation that will transpire over decades.

I don’t want this piece to be a black-and-white, physical media good—digital bad, dichotomy. Rather, this article is more of a reflection on how we orient ourselves around the music we listen to. Ultimately, our LPs and tapes disintegrating is beautiful because it makes them more real and precious in the moment. And we can’t take the Internet’s pristine veneer at face value, because underneath it is just as fragile as the physical. We also need to keep caring about that which we can touch, because as Basinski has demonstrated in his work, we can connect to the frailty of those objects that mirror our humanity. I believe that Basinski’s works of decay remind us of all the impermanence in music, regardless of how we engage with it. However, Basinski noticed the extraordinary relationship between the Disintegration Loops tapes and the copies he was creating when he digitized them. He told NPR in 2012, “…The thing that moved me so profoundly in my studio right after this music happened was the redemptive quality. The music isn’t just decaying — it does, it dies — but the entire life and death of each of these unique melodies was recorded to another medium for eternity.” I could only hope this music will last forever, but I also think it’s okay if not.

– Hannah Blanchette

October 4, 2024 | Blog

Sun Ra and his Intergalatic Friends - Dieswarts CS

Sun Ra and his Intergalatic Friends - Dieswarts CS