Mirrors: A Conversation with Matt Ibarra

For this blog entry, I got together for a conversation with Matt Ibarra, a San Diego-based musician releasing ambient and techno under the name MattxIbarra. Earlier this month MattxIbarra released his tape, Absolute Misery, which is a gripping work of ritual ambient landscapes. Our conversation covered this new tape, his previous work and background, one-hour loop videos on YouTube, Wolfgang Voigt, Hans Fjellestad’s Robert Moog documentary, and more.

Hannah Blanchette: I want to jump right into Absolute Misery and start from there. Can you discuss the compositional and recording process of creating this tape? You had written that it was “meticulously composed and rehearsed then recorded live to 2″ tape.” Can you expand on that and describe that process?

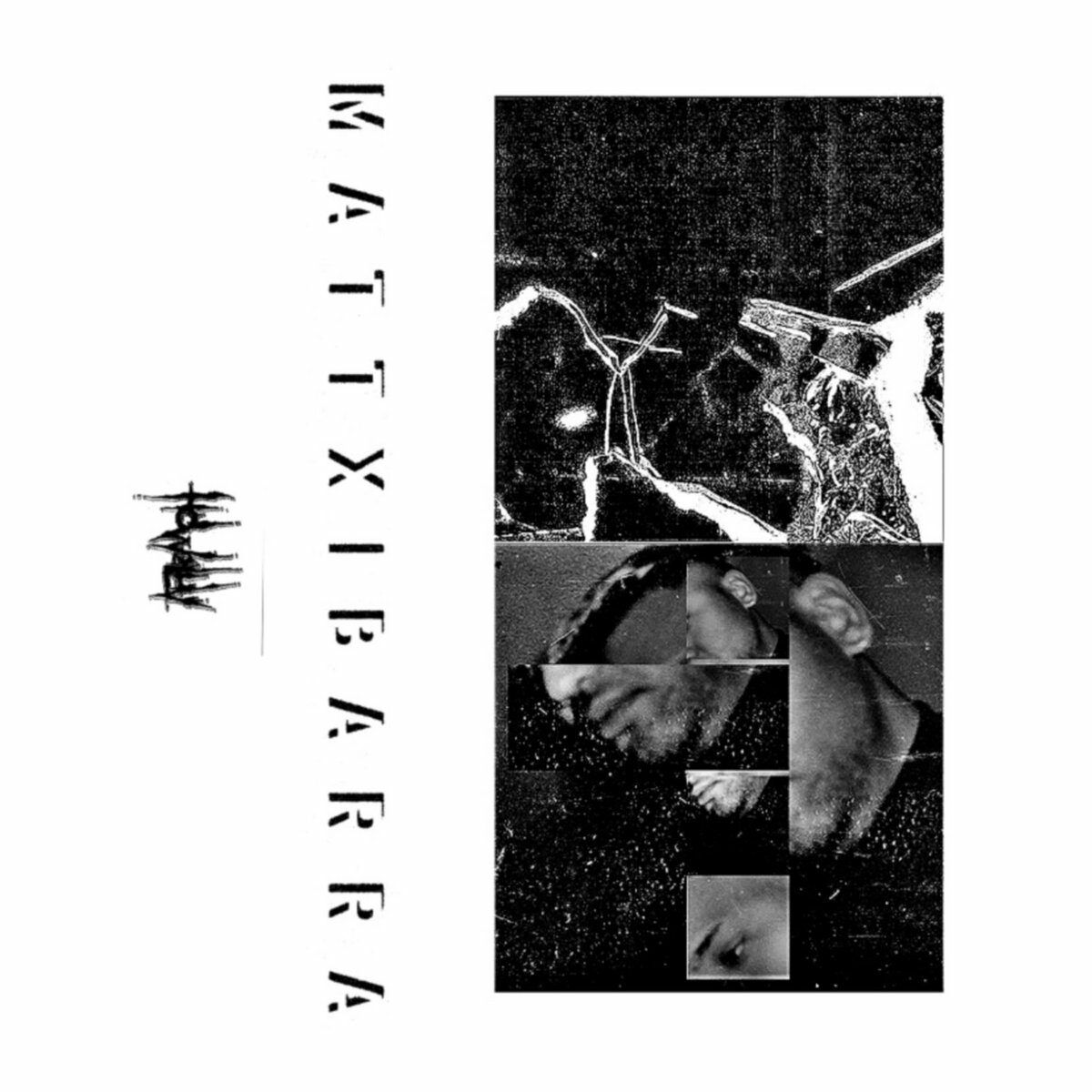

Matt Ibarra: With this particular release, I tried to not be so serious about it. Most of the time I’ll have the music first, and I’ll kind of go along. But for this one, I wanted the artwork to be completed before I composed anything, so that’s where the meticulousness came from. And I never really worked like that. I worked with a homie, Kris, who has a label [Nostilevo], and I linked up with him through a release I was mastering for Omar [Gonzalez] of No Dreams. I was able to connect with him and I asked him, “Hey, would you be down to do some artwork?” I let him know about the process, and he was like, “Yeah, sure, sure, sure.” He kind of works like how I do, when he has time. I waited until I had a connection with the artwork first, and then I created the tones and the ambience and what was necessary to complement the art, versus the other way around. I see colors when I write this type of music. I’ve obviously played in bands and stuff like that, but this type of music that I’m doing now has opened up a visual aspect inside of myself that I didn’t know I had.

The “absolute misery” comes from the unlearning of things. How detrimental it is to your health, your wellbeing, to look away from misery. I tried to compose something that was beautiful in the aspect of darkness. Hence the black-and-white tones. I really try to make it sound pretty. I’ll leave my stuff on, I have a modular setup. I’ll leave my setup, and I’ll tweak it, and it’ll just be on. It was on for months, maybe two months. I never turned it off. Most of my stuff is analog, so once it’s recorded, it is what it is. I don’t really do any editing afterwards. Recording to 2” tape was important because it didn’t allow me to edit down. That was the importance of it all. I wanted the music to be composed and recorded the same way that Kris made the artwork. I’m trying to make these connections more for myself. If anyone can understand what I’m trying to get at, that’s great, but as long as I’m able to look at the artwork and understand for myself that I’ve accomplished some type of progress in this music that I hear.

HB: Yeah, starting there. It should mean something to you and your personal journey, and if it can expand out from there, then that’s an added bonus. Another beautiful aspect of what you make. But it has to start with you, for sure. Can you describe more about how this process you’re describing is similar to Kris’ process with artwork? You said you wanted those two things to match. Is it similar in the sense that you left your modular setup, does he leave art out? How does that work?

MI: How this particular thing came is that we would bounce ideas back and forth. I wouldn’t hear from him for weeks. He would send me something and be like, “Hey, I’m thinking about these type of textures. What do you think about this?” I would say, “I love this, how about we look at this type of overlay?” He wouldn’t respond for weeks. (laughs) That feeling of being just on all the time. That’s what I tried to carry through. I love artists who live with their releases before, during, and after. So I wanted to involve that same process in the recording. And not only the music, but how I approached it. It wasn’t rushed.

HB: Absolutely, I feel like so much is rushed now. Not to get too philosophical, but with the way content works on the Internet, everything’s meant to be pushed out so quickly. Being able to really sit with something, create a headspace for it, I think that’s an amazing way of creating a work of art in a society that tries to push you in another direction.

MI: Yeah, definitely. I just want to touch on this point too, because I just thought about it. Once I feel like I like something, I’m used to just deleting it, and getting rid of it. So this process actually helped me really hone down on living with the tone. There’s no beat, there’s no angle, there’s no endeavor. The only way that I would have been able to tell the story about this record that I lived with was if I took two months of it being on in the studio. I had to say no to a lot of projects just so I could finish this. A couple days off of work too, just chilling, listening, not even writing. Just listening to how my room sounds, how it sounds in my studio. That also helped me, because I have massive anxiety. Massive, massive, massive anxiety. It helped me slow down. Like, slow, the fuck, down. And I want to make more shit like that. And I want people to make more shit like that. So, I love Aphex Twin, right? If you go on YouTube, people post like, a two-hour loop of “Rhubarb,” or whatever. Aphex Twin was a big influence, but it was more the fans of Aphex Twin’s particular songs and wanting to loop that eight minute song for like, five hours. There’s so much on YouTube like that and it amazed me. So I wanted to make this album sound like that.

HB: And you did that. I noticed on your Instagram, you made that one-hour loop of one of your tracks. Can you talk more about that, ‘cause I thought that was a great idea and ties right into this.

MI: I had that loop for myself, with that particular track, just so I could listen to it for myself. I uploaded it to YouTube after the fact. I think the way for most people, with their music nowadays, especially if its outside music, or outside techno, or noise, it’s hard to not come off like, “Oh, hey, can you buy this from me?” And dude, you should be proud of your shit. You should be proud of what you make. And if people want to support it, how are they going to know if you don’t tell people? I’m always trying to think of special ways to share my music and not come off as arrogant or pretentious. If you’re making music for yourself to heal, then you should put a little more effort into sharing it with people who need healing. Those loop videos did that for me for years, and I’m going to do that too for myself. And I’m going to do this for other people. I don’t give a fuck if you buy this, this content’s free. Like yeah, please buy the tape, it’s on tornlight.com. (laughs) But how can I give it to people to where they can have it in their pocket all the time, they don’t have to go to bandcamp.com/mattxibarra and click on the thing, right?

HB: By the way, I think your loop was one of my favorite tracks [from the album] too.

MI: Was it? No shit!

HB: Yeah! I love that one. That track was gorgeous, and a part of me was like, “This could keep going.” I love the hour videos because I definitely need something like that when I’m doing work or trying to read. I have a lot of trouble getting everything out of the way. When I find one track that will completely obliterate everything else for me and encase me in this place where I can get stuff done, I’m just so excited. One of those is “Red Birds [Will Fly Out of the East and Destroy Paris in a Night]” from Coil’s Musick to Play in the Dark. I don’t what it is about that track, but I put that on and I am zooming through stuff. (laughs)

MI: Oh yeah, badass.

HB: That’s why an hour-long version of your track would absolutely have the potential to create that space for me, which is really important to me. So I get what you mean, getting it out in the world so that other people can find a way to make their lives better.

MI: Yeah, and I think too, who’s going to search some random ambient musician from San Diego, California, one hour loop, who’s going to search that? And if you found it, you’re fucking cool. (laughs) You’re looking.

HB: Exactly, this is not just the algorithm doing something. You’re seeing what you can find.

MI: Yeah! I’m always thinking like that. I want to learn more about that type of promotion, using the Internet to do that. I’m sure it’s antiquated, and people would be like, ”You should do x, y, z, or this has been done already.” But you know, I didn’t do it!

HB: Exactly, making your approach and using social media the way you want to use it. I feel like they make it sort of prescriptive, but if you can find a way that works for what you’re doing, then I think it’s a useful tool. So, I want to talk about some of your influences. You had listed Christoph de Babalon, Wolfgang Voigt, and Lee Bannon as some of your inspirations. Can you expand on what about those artists is inspiring to you, or other artists that you want to talk about that have influenced this record or you in general?

MI: Wolfgang Voigt is probably one of my top, favorite producers. I am just in love with him first, and second, his non-aesthetic. For his type of techno, his records are like Beatles records for that type of ambient artist. So he’s like my John Lennon. With Christoph de Babalon, a friend of mine, Florian Kupfer, put me on him and I immediately bought multiple records. Long story short, I just love the lofi-ness of Christoph de Babalon’s imagery. He’s doing jungle, techno, the wrong way, which is fucking beautiful. He just kind of writes backwards. And Lee Bannon, he’s a person of color, like me. I feel like there aren’t many artists like that being represented as they should. There are a lot of artists that are not being represented that are of color. So he is one of my favorite artists in general. He has other projects under different names, but in the album description I wanted to use his name.

With those three together, I really tried to show not only chord-wise, but also texture-wise, how if I was a DJ and I had any of those three artists’ records and I mixed them together, that’s what Absolute Misery sounded like to me. I tried to be a conceptual DJ, mix them together but with my own personal taste. I always try to do that, but I feel like I’m getting better at it at this point. I always think of myself as a student. I try to not have an opinion too much, I’m a very reserved dude in general. I don’t want to overstep, like straight copying this shit, but I definitely wanted to show my influences at this point now. Because my previous releases are really weird, non-influenced. So this tape, which is the most recent tape, is something that I really wanted to show my love to these three particular artists.

HB: I like what you said about being a student, because I feel like that makes it so that your work will always grow too. It won’t stay in one place, there’ll always be something new you’re learning whether it’s about an artist or about a certain technique, it will always be breathing and moving forward. I think that’s a really great approach to have.

MI: I think it being a physical copy, it’s a living document for me to never forget that this is where you’re moving, like stay there. This is where I want to stay.

HB: Speaking of your music in relation to the other releases that you have, you put out the “Head Face & Meat” 12” earlier this year. How do you consider this release in relation to “Head Face & Meat?” Do you have a compositional technique that you find is a thread throughout your work? This one is definitely different from the 12”, so is there anything you consider as a through line?

MI: The one thread I will share with you that’s through every single release since my 2017 LP all the way up to the 12” you talked about and Absolute Misery is my collaboration with the art, the artist. I’m very particular with the art and that definitely dictates what I’m going to write, and then I think about the process. I don’t think about the process before I conceptualize visually what it needs to be. And then, from there I think about what medium the frequencies will best be suited for. That’s why “Head Face & Meat” was on 12”. It was originally supposed to be on a 7” actually, and Alex [York] was like, “Dog, why? This is a 12” dude.” I was like, “Okay.” (laughs) He’s the man, dude. Alex York is the fucking man. So originally it was supposed to be a 7”, and we had to resize all the artwork with that. Musically, the common thread is me. I’m changing all the time. It’s like looking in a mirror. Some people don’t like to look at themselves. They don’t accept themselves. So my mirror is these records. Having it be on a specific medium, then we talk about the process. The process is: if I’m working on a 12”, the frequencies are going to be a little different, I’m going to use different hues, I’m going to sample live kick drum and that’s going to take even longer. If it’s a twenty-minute cassette, I’m going to record on a 2” tape. So the common thread musically is me. What I’m going through is always going to be different. I don’t want to be known as a genre-fluid artist because I’m not trying to jump from genre to genre, it’s not on purpose. It’s because I feel like I’m always being pulled and I let myself be pulled.

HB: That segues nicely into a question I had which is maybe a little genre-y, but I think you also kind of touched upon it earlier when you were talking about Aphex Twin. I was curious what is compelling to you about the ambient genre, or specifically about ritual ambient, which is what you referred to this cassette as. What draws you to playing, performing in this style?

MI: This style really reminds me of how I grew up Catholic. There’s the sermon, there’s this whole order of the music and the structure. And it’s just so vibey. That’s my background introduction to it, and now my grown up essence of it is that this type of music takes me to a place that no other sound or genre can take me to. It takes me to a dark place that I feel afraid of and that I need to explore a little more, because if you’re afraid of something it means you don’t really understand it.

HB: It’s like what you were talking about earlier with misery, like you can’t avoid it, you have to confront that and live in that and feel that.

MI: And I decided to use the word “ritual” because I didn’t want to use dark ambient. So ritual in the sense of that whole church, thick, gothic vibe. But you know, it’s my interpretation. With dark ambient, ritual ambient music, it’s anyone’s interpretation. If I’m going to involve myself in this genre, then I want to make a contribution to it. I don’t want to just add to it, I want to maybe rename it or do something bigger than myself so someone else can feel the freedom that I felt when I heard Gas by Wolfgang Voigt. I just want people to feel a freedom that I felt through this music and that’s why I like this vibe.

HB: Absolutely, that’s spot on.

MI: I felt like I slam dunked that answer! (laughs)

HB: There are two last things that I want to talk about, one is a bit of a backtrack from here, but talking about your musical background, how you came to work in electronic music.

MI: All right, I’m just going to drop this record, you know Björk’s Vespertine? 1999? 2001, so I think I was fifteen-years-old maybe? A duo called Matmos had been utilized to produce those sounds on that record. I googled Matmos and I listened to them and what they actually make and I was like, “Holy shit, what is musique concrète?” I’m fifteen-years-old, mind blown. And I was like, “Fuck Björk dude, Matmos is the shit!” (laughs) From there, I became delusional about what electronic music was, I was listening to everything that had an 808 kick drum. Like Franz Ferdinand had an 808 clap, is that electronic music? I don’t think so. Then I started to get into recording. I went to a recording school in northern California and I interned at a studio called Golden Track Studios in Escondido, California. They had a bunch of synths there, I was maybe seventeen, eighteen-years-old, and I was like, “this is sick, what are these?” But it was hard for me to get up and down over there, so I did my own research and that’s when I was like, “Oh, I can have a home studio.”

That’s when I fell upon Robert Moog and I got into Moog synthesizers, in my early twenties. I learned about synthesis and what an envelope generator was, all stuff like that, and I was hooked. Locally, there was a band called The Locust, and there was a fellow named Jimmy LaValle who played in that band, and he had a solo project called The Album Leaf. That was my introduction to softer, beat-oriented ambient music, but I was more interested in the type of piano he was using. I learned that it was a Rhodes piano. That opened up my mind to different frequencies, and then I was into Brian Eno, Chick Corea, stuff like that, Electric Light Orchestra, they also use Moogs. Going to record stores, digging, “Oh, this Christmas album by Lou Rawls has a Moog in it? Yeah, sure, I’ll buy it.” When I moved to Chicago, it just got weird. I got into power electronics and I got into noise music. I think that was the pinnacle of me deciding what noise is, and what sound is, and what it meant to me.

HB: That’s the key. It’s going to mean something different to everybody. You can hear all this stuff, and you can get all these influences, but ultimately it comes down to you and what your interpretation of it is.

MI: To go back to Robert Moog, there’s a local filmmaker, his name is Hans Fjellestad. He did a documentary on Robert Moog and he went to UCSD. They have a really great electronic music program there, and he was a big influence as far as visual stuff. He is a filmmaker who also loved electronic music, but he didn’t look at himself as an artist. He was in love with synths, but he made films. He was a big influence for me because I don’t look at myself as an artist or a sound designer. I’m a mastering engineer by trade. That’s what I am. But I’m so in love with gear. I have gear acquisition syndrome all the time, I’m buying gear all the time. But I’m also in love with visual art, so Hans Fjellestad was a big influence to me growing up, maybe teens up into my mid-twenties.

HB: Talking about visuals and gear, I also think the way gear looks is so beautiful. Shooting the way a piece of gear looks, with all of the cords coming out of it, all their different colors – especially the old modular synths – all the different input sections, I think they look like works of art.

MI: Oh yeah, I have an original Minimoog Model D, like 1969 or something. If you look inside at the envelope chips, the people who had soldered those, sometimes they put artwork in there, they put little faces. These innovators definitely look as themselves as artists. And the beauty of what knobs you choose to put on your preamps, stuff like that. I feel like I read more manuals than actual books about art. (laughs)

HB: That’s so cool. I’ve got to check out that documentary.

MI: I went to the screening, it was at the Museum of Contemporary Art in San Diego. Fjellestad was right there, I was nervous. I’m still a fanboy. Just a fan, all the time.

HB: I think a lot of musicians are, it’s how you get into what you do. So, what are your plans for what’s up next?

MI: My next album, it’s a little over a half hour. So it’s a big, heavy chunk of music on Amerikan Erektors. It’s a CD called More Silence to Explore. So that’s going to be cool, it’s different. It’s going to be out in 2023. I am working on a tape for a label that I can’t say at this point, but that’s definitely in the works. And I am releasing on my label, h2l, another 12” of mine, and an artist Pablo Dodero, he does techno stuff. He goes under the name Adiós Mundo Cruel. And another 12” by an artist that goes by Desperate Nights. So 2023 is pretty busy. Records for myself and trying to get the label up and running. h2l started as something where I can release my own music under an entity, but after this 12” of mine, I don’t think I’m going to release anything of mine on that label anymore. I’m just going to focus on 12” wax for artists that I fuck with. I’m also working on a mix for this station called Particle FM based in San Diego. It’s going to drop January 6th and I have a bunch of unreleased stuff from artists that I’ve mastered. It’s basically stuff that I’ve worked on that I’m really stoked about. It’s going to be sick. I have intertwined between the tracks Marcel Duchamp interviews, him talking, it’s fucking fire! (laughs) ‘Cause in between he talks about having no taste. It’s cool, it’s dark.

In the Shop

Mattxibarra – Absolute Misery – $9

MattxIbarra – Head Face & Meat 12″ – $20

MattxIbarra (H2L Reissue) – $30

Note: This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

– Hannah Blanchette

December 31, 2022 | Blog