John Cage’s ‘Organ2/ASLSP’, Slowing Down, and Artistic Longevity

Recently, I was trying to look up a specific topic related to John Cage in Google News and was having trouble getting results. I searched simply “john cage” to see if I could could get any results and I stumbled upon all of the news articles about his piece, Organ2/ASLSP (As Slow As Possible). A notable, ongoing performance of the piece in Halberstadt, Germany, had the most recent note of the piece played back in February, with the next note set to be performed in 2026. The entire performance is projected to finish in 2640.

The prospect of a performance that lasts over six hundred years is presumptuous, ambitious, delirious, and optimistic. Outside of the logistics of a performance of that magnitude, it is bold and daring to assume that interest in John Cage will resound for over half a millennia, and that the Earth will still be in good enough shape (or even exist) to support the piece’s performance. The John Cage Organ Foundation has taken care of the first of these elements, the continued interest in medieval chant from the ninth and tenth centuries is a proven example of the longevity of a particular style of music or composer, and of course it is up to us to preserve the Earth for another six hundred years.

But what I find most fascinating is the concept of interest in a piece that is supposed to be performed “as slow as possible.” We exist in a world where pop songs are manufactured to produce the catchiest ten seconds possible for TikTok, seasons of television shows are shortened so that they can be binged in a night like a long-ish movie, and people often only read an article on their phone for a few seconds before moving on to the next thing (if you’re reading this part of this blog, you’re already ahead of the curve). In this context, the idea of a six-hundred-year-long performance is utterly radical. Awaiting the next change in the piece feels like anticipating a rare celestial event, like a total solar eclipse or meteor shower.

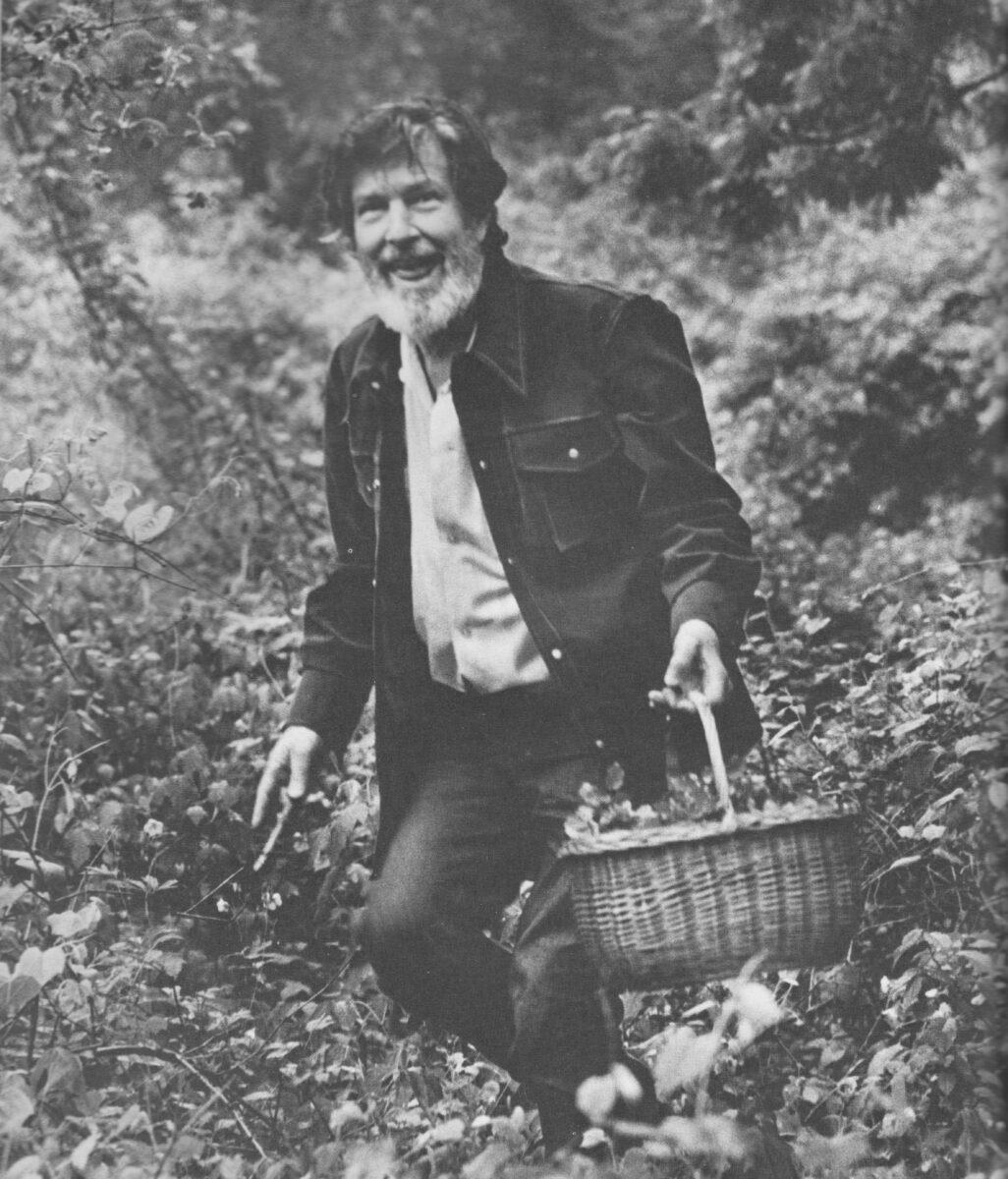

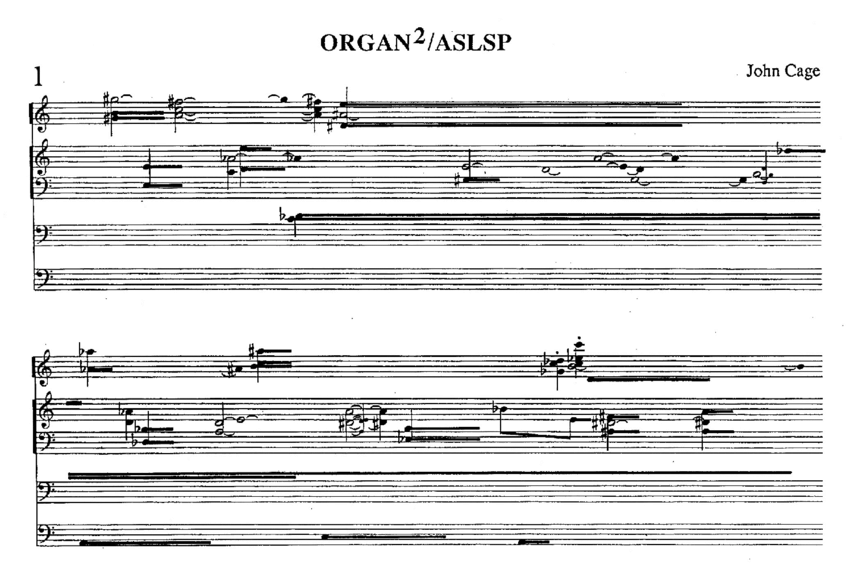

John Cage wrote Organ2/ASLSP in 1987, an adaptation of his piece for piano published two years prior. While there have been various performances of the piece that do not aspire to the degree of “slowness” of the Halberstadt rendition, the latter is the most famous performance of the piece. Musicians and scholars gathered in 1997 to discuss the implications of Cage’s instructions and organized the literal slowest possible performance, with the decision to have the piece played for 639 years, the amount of time passed since the first twelve-tone organ was invented in Halberstadt (1361) by the year 2000. The performance began on September 5, 2001, using sandbags to hold down each note played.

Organ2/ASLSP first reminded me of La Monte Young’s The Tortoise, His Dreams and Journeys, which began composition in 1964 by initiating a drone with his turtle aquarium’s motor, and is still ongoing. As Young states, “This music may play without stopping for thousands of years, just as the Tortoise has continued for millions of years past, and perhaps only after the Tortoise has again continued for as many million years as all the tortoises in the past will it be able to sleep and dream of the next order of tortoises to come.” The New York Times published a piece in 2016 that noted the significance of turtles to the New York downtown scene, citing Meredith Monk’s affection for her turtle Neutron, of whom she said, “…Everything is slow with her, so it just reminds you to slow down a little bit. I like the reminder of a more ancient time — or a timelessness.” The impetus behind Young’s piece, as well as Monk’s interest in turtles, is the symbolism of slowness and timelessness, a concept of longevity that cannot by achieved by the composer’s mortal bodies, but can be achieved through their music.

Concepts of stasis, stillness, and being present in the moment can be found across the avant-garde, drone, and electronic music. What intrigues me about the Halberstadt performance of Organ2/ASLSP is the power of its implications now, and how many people still exude enthusiasm about a piece that is taking 639 years to complete. 150 individuals paid in advance for a front-row seat to the next change in the piece, and the church could seat 500 with its capacity. There are people that genuinely care about experiencing the slowness of the piece, and are not bothered by the fact that they will never hear it finish. John Cage Organ Foundation member Anneli Borgmann said, “My lifetime is no more than the blink of an eye – I came to terms with that long ago. To me, Cage’s piece speaks of an incredibly stubborn optimism: we will die, but this work of art will live on for generations.”

When Cage’s piece was published in 1987, society was also going through rapid technological change, especially by way of the personal computer, with the World Wide Web’s launch to the public in 1991 only a few years away. The world was getting faster, and information was circulating more quickly and constantly, such as through the burgeoning 24-hour news cycle we accept as the norm today. Could Cage’s desire to publish pieces meant to be played as slow as possible have been a response to the increasingly wired world he was witnessing in his old age? Perhaps. Regardless, it certainly resonates now. I love the idea of continued passion for John Cage generations and generations into the future. I love the fact that I will not live to hear the final note of this piece fade out of existence. Simply reflecting on these facts slows me down a bit, making me realize that not everything needs to happen in a split second. I can’t take six-hundred years, but I can take a breather for a little while longer.

– Hannah Blanchette

August 29, 2024 | Blog