-

×

Bomis Premdin - Clear Memory

1 × $25.00

Bomis Premdin - Clear Memory

1 × $25.00 -

×

Saturn And The Sun - The New Age Is Shit

1 × $7.00

Saturn And The Sun - The New Age Is Shit

1 × $7.00

Subtotal: $32.00

Probably like many who listen to the twenty offerings from Black Jazz Records, the Oakland-based jazz label from the seventies, my first encounter with their catalog was with co-founder Gene Russell’s New Direction. Released in 1971, we were fortunate enough to have an original copy for a little while here at the shop. Like with many rare records, if we have the opportunity to play an original version during the workday, we take it. Many times. And without fail, that bouncy, energized opening piano riff on “Black Orchid” drew me in, my feet beginning to bounce along with it.

Probably like many who listen to the twenty offerings from Black Jazz Records, the Oakland-based jazz label from the seventies, my first encounter with their catalog was with co-founder Gene Russell’s New Direction. Released in 1971, we were fortunate enough to have an original copy for a little while here at the shop. Like with many rare records, if we have the opportunity to play an original version during the workday, we take it. Many times. And without fail, that bouncy, energized opening piano riff on “Black Orchid” drew me in, my feet beginning to bounce along with it.

The opening of “Black Orchid” truly signaled a “new direction” for jazz, Black Jazz entering the scene during an era when the influential jazz labels of the previous twenty years, such as Blue Note, Impulse!, and CTI were being swallowed up by major labels. Russell and co-founder Dick Schory of Ovation Records didn’t allow these industry trends to sway them from starting a small jazz indie that valued Black musicians and their artistic decisions over commercial prowess. From the spiritual and free to the soul and funk-infused, what mattered most was that the artists had the space to express themselves in whatever approach “jazz” meant to them.

Gene Russell promoted Black Jazz as a label by and for Black people, because as he stated, “too many Black jazz artists are being denied to showcase their talents.” At that time, white critics in particular bristled at Black Jazz’s approach to only put out music by Black musicians, claiming jazz as music of all people. However, framing jazz in that way glossed over the relevance of jazz to the history of Black art, especially in America, and allowed for complacency in the industry so that racial inequity could continue to thrive. One response from Russell to these sentiments included, “You see, this is what happens when a Black person makes a statement in this day and age. A group of people may say we want our own land, do our own thing – and the first thing white people will say is ‘racism.’ Yet his control of our people has been going on for hundreds of years. This is why I made the statement; I believe everybody should get their just dues.” Label artist Kellee Patterson emphasized the power behind Gene Russell’s mission, saying that Black Jazz “was about making sure that Black artists were more represented, because so many of them had their work stolen and never got the benefits of it.”

Black Jazz weren’t the only ones centering Black performers in its output during this time period. A notable fellow example from this time period was Black Fire, a Black-owned, Afrocentric label from DC which focused on releasing records by Black artists from DC in jazz, soul, funk, and go-go. Furthermore, various Black artistic collectives sprouted up across the US during this time, including Los Angeles’ Union of God’s Musicians and Artists Ascension, the Chicago-based Association of the Advancement of Creative Musicians, and the Black Artists Group in St. Louis. Following the thrust of the Civil Rights Movement, Black Power, and the Black Panther Party (who were headquartered in the same city as Black Jazz), the seventies saw a period in which Black musicians sought ownership, control, autonomy, and ample artistic space to create self-sustained art unfettered by the values of white society.

Black Jazz’s values can be seen in early descriptions of the label, such as in this 1971 Billboard issue, which states that Black Jazz was “owned, operated, staffed, and aimed” towards Black people, and quotes Russell stating that Black Jazz was “aimed at the black community and only black artists will appear on the label.” The article also makes a point to note that Russell would be producing and engineering the early Black Jazz titles and he would have “complete artistic control.”

This Billboard article also discussed the manner of packaging Black Jazz releases. Each Black Jazz album had a white-on-black color palette, with the title visible no matter how the record was placed on the record store rack. The label also purposefully made sure to include the artistic credits on the sleeve, often on the cover. This distinctive design approach was even copyrighted by the label. Black Jazz’s dedication to artists is apparent through this design, which foregrounds the people involved in the record-making process and conveys that information through a simple, minimal design. Furthermore, Black Jazz albums garnered audiophile status, with each release boasting a quadraphonic version.

This Billboard article also discussed the manner of packaging Black Jazz releases. Each Black Jazz album had a white-on-black color palette, with the title visible no matter how the record was placed on the record store rack. The label also purposefully made sure to include the artistic credits on the sleeve, often on the cover. This distinctive design approach was even copyrighted by the label. Black Jazz’s dedication to artists is apparent through this design, which foregrounds the people involved in the record-making process and conveys that information through a simple, minimal design. Furthermore, Black Jazz albums garnered audiophile status, with each release boasting a quadraphonic version.

The ownership behind Black Jazz has been the cause for some contention over the decades. Despite Black Jazz’s longtime reputation as the first Black-owned jazz label for decades at the time, the percentage of ownership that Gene Russell had often has been fuzzy, and the label has been passed around various white owners since Russell’s death in 1981. Also, many Black jazz artists throughout the genre’s history have started their own labels to release their material, even before Black Jazz’s founding. Examples include Sun Ra’s El Saturn, Charles Mingus and Max Roach’s Debut, and Betty Carter’s Bet-Car. Despite all of this though, the number of Black artists running jazz labels has been historically disproportionate to the number of Black musicians driving the genre, and Gene Russell’s ownership of Black Jazz carried a lot of meaning for the Black community. For those curious, the details of these ownership disputes were covered in a 2020 Washington Post article.

Ultimately, Gene Russell did wield artistic control of Black Jazz, curating jazz from across the spectrum of what the genre sounds like from artists looking to “get in the door,” as Henry Franklin has said. Below, I briefly discuss three Black Jazz records I especially enjoy.

Doug Carn’s Infant Eyes was one of the earliest releases on Black Jazz, a spiritual record that took inspiration from influential African Americans such as John Coltrane, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., and Muhammed Ali. Jean Carn performed vocals on the record and had experience writing lyrics for musicians such as Coltrane, Wayne Shorter, and McCoy Tyner. The Carns brought Infant Eyes as a demo to Russell and he did not even have them re-record anything. I completely understand. Gripping from the ethereal opening of “Welcome,” Jean Carn’s voice swirling around the sparse instrumental texture, this record is solid spiritual jazz. Her voice calls to mind June Tyson of Sun Ra’s Arkestra, who I covered earlier this year. Each track offers something so different on this record, and is a great place to start in Doug Carn’s four offerings for Black Jazz.

Doug Carn’s Infant Eyes was one of the earliest releases on Black Jazz, a spiritual record that took inspiration from influential African Americans such as John Coltrane, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., and Muhammed Ali. Jean Carn performed vocals on the record and had experience writing lyrics for musicians such as Coltrane, Wayne Shorter, and McCoy Tyner. The Carns brought Infant Eyes as a demo to Russell and he did not even have them re-record anything. I completely understand. Gripping from the ethereal opening of “Welcome,” Jean Carn’s voice swirling around the sparse instrumental texture, this record is solid spiritual jazz. Her voice calls to mind June Tyson of Sun Ra’s Arkestra, who I covered earlier this year. Each track offers something so different on this record, and is a great place to start in Doug Carn’s four offerings for Black Jazz.

Tower of Power fans, I’m looking at you. If Chester Thompson’s keyboard parts during Tower of Power’s legendary lineup for most of the seventies are particularly appealing, check out his first record as bandleader, released by Black Jazz in 1971. Hammond organ-driven jazz-funk that’s as catchy as it is virtuosic, with label mate Rudolph Johnson playing some fire sax solos as well. Laid-back, but with firm grooves too.

Tower of Power fans, I’m looking at you. If Chester Thompson’s keyboard parts during Tower of Power’s legendary lineup for most of the seventies are particularly appealing, check out his first record as bandleader, released by Black Jazz in 1971. Hammond organ-driven jazz-funk that’s as catchy as it is virtuosic, with label mate Rudolph Johnson playing some fire sax solos as well. Laid-back, but with firm grooves too.

Kellee Patterson’s musical genesis is slightly unorthodox, which is part of what drew me to her Black Jazz release in the first place. Patterson was the first Black woman to win Miss Indiana in 1971, with her singing talent helping bring her to victory. Despite catching the ear of Motown’s Berry Gordy, Patterson took up Russell’s offer on Black Jazz instead for her debut record. Patterson’s voice is spell-binding, and I often find that I completely get lost in it. The record moves from languid tracks with mystical flute to upbeat soul tracks, constantly keeping me on my toes.

Kellee Patterson’s musical genesis is slightly unorthodox, which is part of what drew me to her Black Jazz release in the first place. Patterson was the first Black woman to win Miss Indiana in 1971, with her singing talent helping bring her to victory. Despite catching the ear of Motown’s Berry Gordy, Patterson took up Russell’s offer on Black Jazz instead for her debut record. Patterson’s voice is spell-binding, and I often find that I completely get lost in it. The record moves from languid tracks with mystical flute to upbeat soul tracks, constantly keeping me on my toes.

“Black Jazz Records Special,” NTS (2022)

“Black Owned Jazz Label to Bow With Black Acts Only,” Billboard (1971)

Geoff Edgers, “It Was the First Black-Run Jazz Company in Decades. But Was Black Jazz Records Owned by a White Guy?,” The Washington Post (2020)

“Floating Points, Gilles Peterson, Theo Parrish and More Break Down Their Favourite Records from the Black Jazz Records Archives,” Crack Magazine (2019)

Uchenna Ikone, “Black Jazz: A Revolution in Sound and Style” Superfly Records (2019)

Martin Johnson, “Rediscovering The Enormous Social And Spiritual Legacy Of Black Jazz Records,” NPR (2020)

“Kellee Patterson: A Maiden Voyage,” Voices of East Anglia (2012)

Nate Patrin, “An Introduction to Black Jazz Records,” The Vinyl Factory (2019)

Chris Robinson, “‘Jazz Is Black and Must Be Kept That Way:’ The Black Jazz Records Essentials,” Passion of the Weiss (2021)

Giovanni Russonello, “The Small, Black-Owned Record Label That Made a Big Impact in 1970s D.C.,” The New York Times (2020)

“A Tribute to Black Jazz Records”

You can also view all of these under the Black Jazz page.

Gene Russell – New Direction (also CD)

Walter Bishop Jr. – Coral Keys

Doug Carn – Infant Eyes

Rudolph Johnson – Spring Rain

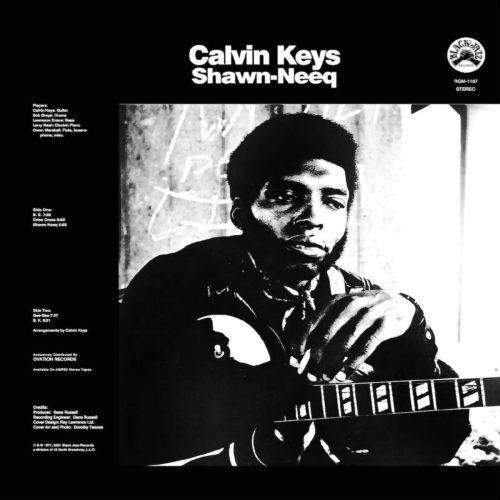

Calvin Keys – Shawn-Neeq

Chester Thompson – Powerhouse

Henry Franklin – The Skipper

Doug Carn – Spirit Of The New Land

The Awakening – Hear, Sense & Feel

Gene Russell – Talk To My Lady

Rudolph Johnson – The Second Coming

Kellee Patterson – Maiden Voyage

Walter Bishop, Jr’s 4th Cycle – Keeper Of My Soul

Doug Carn – Revelation

Henry Franklin – The Skipper At Home

Cleveland Eaton – Plenty Good Eaton

Doug Carn – Adam’s Apple

Calvin Keys – Proceed With Caution

– Hannah Blanchette

June 5, 2022 | Blog