In the Improvisational Moment: An Interview with Alex Cunningham

Tomorrow evening, Torn Light Records is thrilled to host a performance by solo violinist, improviser, and visual artist Alex Cunningham from St. Louis. We are big fans of Alex’s work here at the shop and he also released his album, As Slow as the Stream on our own Alex York’s CD imprint, ARKEEN, last year. The show will begin at 9pm tomorrow, June 18th, opened by Torn Light’s seven-piece house band, Poem of Chairs.

In anticipation of Alex Cunningham’s appearance, I had the opportunity to chat with him about his musical background, influences & inspirations, musical process & collaborations, visual art endeavors, and what’s in store down the line.

Hannah Blanchette: I was thinking we could start off talking a little bit about your musical background, how you came to the violin. Start there and eventually have that tie into your recent release, For Student Violin, which is very cool.

Alex Cunningham: I started playing violin – it wasn’t my first instrument – but I started playing violin in third grade. I went to public school and I was lucky enough to still have a public school orchestra program at my school, which I don’t think it exists where I went to school anymore. So I started in third grade through school. My older brother played violin as well, so I started a little bit earlier with him, just going through his books and stuff like that. I had played trumpet two years before because I had an uncle who was in military bands forever, so he showed me how to play trumpet. And then I played piano for a second as a little kid. I always wanted to play music and neither of my parents were musicians, so it wasn’t a thing that was around. But I was always drawn to it. In middle school and high school, I started doing the regional orchestra stuff in Milwaukee, where all the different kids from different schools are playing in orchestras. The whole classical music background thing. I started playing guitar at the end of elementary school and did the total, “I want to rock! I want to shred!” young boy cliché stuff, and then found punk and things like that later on. Those were all my entryways to any experimental music, through finding punk rock and things like that.

For Student Violin was like: I got that violin – which was my first one – the three-quarter size violin that I learned on that was also my older brother’s. I got that back from my parents just because they had it, and a few years ago they were like, “Do you want this for anything?” I was like, “Yeah, I’ll figure something out with it.” I wrote a piece that I wanted to do as a live performance that was going to end with me destroying it. I never got it to a place where I wanted it to be. I started psyching myself out about doing it because I was like, I can only do this once, and what if I do it at a show to three people and I don’t document it well or something. My original intention for the live thing was I was just going to perform all of Suzuki Book 1, the Suzuki violin school performance book, and do everything in order and then destroy it at the end. But then, this was right before the pandemic, so then that all happened and I wasn’t thinking about it. And then I moved recently and in moving was like, “Oh yeah, I have this violin. I might as well do this.” I’d gotten into home recording again, so that became the idea of the lathe thing. Just going through all the music that was still in there, and it still had all my elementary school and high school music, and things like that. It was funny to see people react to it, because it’s you destroying something and people thought that there was some, “Oh, I’m exercising some negative connotations of learning music,” or something like that. I don’t view it that way at all. It was more like dropping baggage and moving on in a positive way. Or I was more interested in the Fluxus angle of this as this object that I learned on, and now there’s twenty people that have it in different areas of the world. It’s funny you brought that up. That was a really fun project to do.

HB: For me, I learned clarinet in school through college, and I don’t know if I could do that with my first clarinet. I feel like there’s so much sentimentality there. What did you experience through that process of destroying something, an object that was such a part of your life for a period of time?

AC: I think for me, I felt more of that going through making the artwork, because I was going through school assignments and seeing music theory tests from fourth grade. It’s like I-IV-V chords. Seeing that stuff brought more back. It was easy for me to let go of the object, in a simple way, just that it doesn’t have a practical use for me because it’s not a full-size violin, so it’s super tiny. Maybe I would have kept it to play or make noise with if it was playable and full-size or something like that. The violin I play now is my second violin, I’ve only ever had one full-size instrument. So I do have some of that sentimentality with the instrument I play now. Maybe if it was like, I just played one, and then I just got a new violin it would have been harder to let go of or do that to. But I think because it was just this cheap-o, rental-to-own Suzuki violin, I didn’t have a ton of attachment to it. And also, living in small apartments and being like, “Well, I gotta get rid of something.” (laughs) I can’t have all of the instruments and guitars and shit unless I’m playing them all the time.

HB: Can’t have the clutter. I think I’d read that the A-side was you playing that violin. Was it really awkward after playing a full-size violin for years to be able to play that smaller one again?

AC: It was very interesting. It was hard to play. My hands felt so big on it. I hadn’t even thought of the practical aspects of actually playing it. The solo that I ended up doing, for that reason, leans very into doing extended technique stuff on it because it was physically hard for me to play lyrical stuff on this tiny violin. Bowing was really hard, it was hard to be able to bow a single string on it, just because it’s such a small scale. The solo I’m playing on it, I’m doing really abrasive stuff and I play it with a screwdriver and stuff like that.

HB: Yeah, make it work for what you’re doing at this point in your life.

AC: Yeah, for sure.

HB: So, you talk about punk being an avenue into experimental. Could you elaborate a bit on that process of coming into doing experimental and improv music?

AC: My entry point into everything in terms of music was like, music was around, my parents listened to music a lot. But neither of them were heads or neither of them were in academia, so it’s not like I was finding out about John Cage or something from parents. My dad listened to Motown and eighties R&B. And my mom owned like, five records, and they were like The Carpenters and Heart, and stuff like that. I remember when I was playing guitar, that was big because I started listening to a lot of guitar-centric music. And then somehow, I found nineties stuff, like Built To Spill, like nineties, guitar-driven stuff. I had an older brother too who was listening to that kind of stuff, like Built To Spill, Pavement, nineties, guitar-driven indie rock. In middle school, I read Our Band Could Be Your Life and got really obsessed with everything in that book. So I got really into SST, and then my favorite band was Sonic Youth. The great thing about them was obsessively going through their catalog, and they did those weirder collab albums and the SYR stuff. It’s them playing with a bunch of names I’d never heard of and I just started looking up any of the people they were playing with. They’d play with Mats Gustafsson, and there’s a record that’s them with the Instant Composers Pool free improv people, and there’s a record with them and Merzbow. So I was in eighth grade and going through every Sonic Youth thing I could get my hands on and looking up anyone they played with. They’re also one of those bands where it’s like, in the way that Kurt Cobain was always referencing certain stuff in interviews, they were always name-dropping different stuff, including visual artists. I feel like they still, for people and definitely for me, were such a great gateway into not only more experimental music but also more experimental film and visual art. I feel like they had such a connection with that.

So I got really deep into the entry points that were like Merzbow, noise, stuff that was accessible. Pretty much anything in that orbit that I could get from my library as a high schooler, I would get into. I would obsessively fill out Interlibrary Loan requests. I’m sure the library I went to all the time was super annoyed with me. I remember getting a copy of The Ascension, it’s that Glenn Branca record, and not understanding that I requested a vinyl record, so that got sent to pickup and it’s like, “You have a return in a week.” I had to get my mom to set up her turntable that she had a million years ago to be able to listen to it. In terms of playing that kind of stuff, I feel like up until the end of high school into college, I never thought about trying that on violin. Like, the second I heard Sonic Youth I started playing my guitar with drumsticks and screwdrivers, but I never thought to start trying that stuff on violin. I think once I started to hear stuff that had violin in it, then it was like, “Oh okay, I want to be able to learn this. I can play violin outside of a classical music context or a folk context or fiddle context.” Because for me then, it was like anything I was playing in school, that’s what I play violin on and then I play guitar in shitty high school bands. That’s where I play more punk or weird stuff. Starting to hear stuff that I liked where it was like, oh, this is a pretty violin-centric band, like Dirty Three or something like that, that’s when I was like, I have songs I want to learn outside of that by ear. So that wasn’t necessarily experimental music but that was the stuff as a teenager that got me excited about playing violin in this context that existed outside of classical music that I played in school.

Then once I got to college and started playing with people, I was still playing guitar and it became this thing where it was like, “Oh you also play violin.” And my violin had a pickup, I liked messing around. So it became this thing of people were interested in playing with someone who played violin and because I started playing in experimental contexts, that quickly became the thing that I was playing all the time. Also for me, at the same time, is that it quickly became a thing as I was getting really obsessed with improvisation. As I was starting to improvise on violin, it was easier for me to find what I felt like was a distinct voice for myself on violin than on guitar. I felt like there were certain things I could really lean into on violin that I was already doing messing around at home as a kid, that you can’t really do sonically on a guitar. Like, it’s a fretless instrument, so you can do a lot of things that you can’t do on guitar on that. It’s bowed, so there’s so many different sounds you can get just out of your bow hand that I felt like I couldn’t do on guitar. It started to feel like playing guitar in improv contexts was like, I could either be a low-rent Derek Bailey rip-off or I could really focus on this instrument that people want to play with because there’s not anyone here doing that. Also, I feel like I have more of a connection to it and could do something unique that is more of a reflection of me, rather than just – improv guitar! I don’t know, a Bill Orcutt rip-off or something. And I say that just for myself, not that improv guitar is a rip-off of those things. I absolutely love guitar in an improvised context. I just mean that for me trying to play guitar in an improvised context, it was like I sounded like a watered-down, less-interesting version of these two people whose guitar-playing I really enjoyed. I felt like I was able to play violin in a way that was a more honest expression of myself.

HB: Exactly, carving out your own space.

AC: Yeah, for sure. I thought it was a truer, in some way, representation of what I wanted to do.

HB: Can you talk a little bit about the different extended techniques that you use on violin and describe some of them? And you can pick a recent release like Two for Olivia or As Slow as the Stream. Talk about how you create some of these sounds and what people can listen for.

AC: Let’s start with Two for Olivia. I feel like the B-side – the electric thing – when I do electric I try to keep my gear setup pretty simple. It’s more rewarding for me to not get super into pedals. For one, I want it to be something that’s just a little bit of an addition to what I’m doing already, rather than, I either do acoustic stuff or stuff with a million pedals. And two, that shit is expensive. (laughs) I just don’t want to go down that rabbit hole. Also, it’s easier for me to learn how to do three things at once instead of a million. When I play electric I do a lot of extended stuff that you can do when it’s acoustic but picks up better amplified and distorted. A lot is manipulating the face of the instrument. I do a lot with the F-hole itself, so if I make sound into it, it will pick up really well if it’s distorted through the pickup. I’ve done that on acoustic releases, like there’s one called Knell from a few years ago that has a piece called “Piece for F-hole and Breath” that’s just me breathing through the instrument. I do that on pretty much all the electric stuff, it’s just without the visual of it, you can’t tell. There’s a lot of me breathing through the F-hole, I’ve done whistling through the F-hole. There’s a little bit on that record. And then a lot of using brushes, like drum brushes on the face of the instrument or having it on my lap and scraping the top of it. There’s a lot of those kind of sounds when I do electric stuff. So much of the harsh stuff is just bow hand. Doing this really aggressive, leaning in, really ugly bow hand stuff. That’s all over that tape.

As Slow as the Stream, it’s funny for me, I feel like that’s the more accessible stuff that I do. Which is funny because it’s a thirty-four minute violin solo, so the packaging itself is not accessible but I view that one as a really accessible record. I feel like that’s my pop album. (laughs) The extended technique stuff on that, that’s all in an open tuning. Kind of riffing on fiddle and American primitive. I lean really hard into using tons of harmonics and have constant overtones on there. A lot of that is bowing, but then also I de-tuned the instrument a couple steps so I get really rich, harmonic stuff coming out of it. I do that a bunch too, a lot of alternate tuning stuff which I think makes for really interesting sounds on the violin that you might not get otherwise.

HB: I really like the color palette that can come out of an instrument like the violin. It’s so cool. Kind of on that note, you’ve talked a little bit about your improvisational/compositional process. How do you approach making a record, and on the other side, how is that approach maybe different when you perform live?

AC: Yeah, that’s a really good question. I know the majority of my stuff aside from a few things is completely improvised, so it’s definitely dependent on if I’m playing solo, in terms of a recording, or playing with people. The process there is trying not to think about it until you’re listening back. Improvising with people or improvising alone, trying to be in the moment and then getting things back and deciding what makes an album. I don’t know how to articulate that, it’s just what makes sense in terms of flow, whether or not it’s a release with sides, all those normal things. That’s the hardest part for me for recording improvised music is figuring out sequencing and titles because everything’s so abstract. For compositional stuff, there’s a few projects where I went in knowing what I was doing, like Ache is composed, loosely composed, it’s got sections. That came out of playing that live at the time. Pre-pandemic, if I was working on an idea, I’d try to play a lot of shows if it wasn’t something that was improvised. So that was something that came out of playing electric shows. I think I played a little under ten shows of doing that idea before it became the thing that’s on the record, and then I did a tour, the only time I did a tour where I was playing the same set every night, basically. Split into compositional sections and then I can play those sections as long as I want or improvise within them. The Rivaled tape was something where it’s like, “I know what I want this to be.” That was maybe the most conceptually thought-out thing before I went into it. Mostly, the rest of my solo stuff is improvised. I think As Slow as the Stream was a little bit thought-out, and that I wanted to see if I could do a durational thing. If I’m trying to do something that is loosely compositional, I like to try to keep it loose. I want to get more into strict composition, but in the last couple years it’s worked better for me as a process if I’m doing something on the more compositional end of what I’m doing, then having it be loose structures rather than really strict structures.

There’s one album the guys from Crazy Doberman put out as a tape, where I think I experimented the most and that just came out of them being like, “The weirder, the better.” There’s one piece on it that’s multi-tracked, low-budget musique concrète recorded in my apartment. It started out of how, during the pandemic, trying to record solo improv is so difficult. My neighbor was super loud, you get a ton of ambient, street noises, and then I have a dog. I would only be able to do so many takes before he’d bark at something or something would happen, the neighbor would come home. There’s a piece on that tape where it came out of trying to record improv and listening back to something where I stopped because my dog started barking. I was like, “What if I had the piece be ambient sounds of my house, and then my dog barking, and then I play over that later?” So I got tons of takes of my dog interrupting recordings and threw it on there. I don’t think I have a specific thought process in terms of any of the improvised stuff. It’s more of like, who am I playing with, try not to fuck this up. (laughs)

HB: I think that going in with a free mindset allows for the creativity.

AC: And frameworks can be really good! I’m not against any of that. I’m not a free improv purist.

HB: Speaking of collaborators, you’ve been able to record and collaborate with some big figures in experimental music, like Lisa Cameron, Claire Rousay, Mark Shippy, Damon Smith. Do you want to talk about how you came to work with these individuals, what drew you to working with them, talk about these experiences?

AC: Well, Claire is interesting to talk about for this because I met her in Cincinnati actually, which is funny. We played a show – I was on tour in 2017 – and we were all on the same bill. It was her and More Eaze on tour. We became friends, we played what ended up being this horrible show in Cincinnati. We were supposed to play this venue that we were all psyched about, that everyone was like, “legendary, local DIY space!” Rake’s End, I think it was called? This was years ago, I guess it had been there forever and while I was on tour, three days before that show it closed, there was some horrible thing. So it got moved to some random bar and we ended up on this mixed bill where they took the three experimental acts and put them on this show that was like, a singer-songwriter who wasn’t on tour – it was really bizarre, like they flew in from Nashville to play this show at this bar and that was it. So it was us bookending this singer-songwriter country set, and the sound guy was very mad at all of us for no reason. It was really funny, we had this shared, weird experience. And she was touring for a really long time then, so she would come through St. Louis all the time and we became friends through that, started playing together. And then during the pandemic, she stopped focusing on drums and started doing the more ambient, personal stuff. That became a long distance thing of like, “Hey, I’m working on this, can you play violin over these chords?” I think I’m on four of their things, and that was all a very short period, recorded in my apartment when everything was shut down. The first one I play on, I didn’t have home recording stuff yet, and I think it’s “It Was Always Worth It,” I play on that one and that’s literally just iPhone voice memos. (laughs) So that’s how I started working with them.

Mark was through my friend Bob Bucko who’s great, who does the label Personal Archives. He’s in Dubuque, Iowa. He’s known Mark forever and he knows that I was a huge U.S. Maple fan. He asked if we wanted to play. We had all played in a quartet with this drummer Alexander Adams in Chicago while we were all on tour a few years ago. The summer after that, Bob was like, “Do you want to make a record with Mark? I think I want to get into doing vinyl.” That was years ago, we were able to finally do something a year in, and that was great because it was a friend being like, “Oh hey, I’m good buds with the guitarist from your favorite band, do you want to make a record with him?” That one cosmically fell in my lap. Mark’s amazing, he’s great and we became friends through that. We played a handful of shows, did a recording we didn’t use for the record before because we played way too long. (laughs) The first time we played together there were no pauses and we didn’t realize how long it was. Each piece was like, thirty minutes long with no spaces. It’s very silly. We couldn’t cut it down to a record. But we got to play together. That’s how I met Mark, that one was a no-brainer, do you want to do this cool thing? I wish that happened all the time. I wish more people would be like, “Do you want to record with this amazing person and I’ll put it out?” Mostly everyone I’ve played with are people that I’ve met because they travel a lot, or come through or I met them on tour. Lisa’s that way, she tours a lot in a lot of different groups. Everyone’s like that. Damon I met because he moved to St. Louis.

HB: I feel like in so much of experimental music, at least in this area of the country, a lot of these people collaborate with one another. It’s really cool to see. It’s like, “Now these two are doing something together!” It’s a great exchange. I love seeing a record with two really cool artists working together.

AC: Yeah, I feel like that’s the most fun aspect of listening to this music too. It’s got the quality of baseball card collecting. Jazz is that way too, where it’s like, here’s all my favorite people and now I can try to find everything they’re on, and they play in all these different combinations. I love it, it’s great.

HB: That’s a great point about the jazz records, it’s really fun to see everybody working together. I was curious to talk about how you came to create visual art as well, and how does visual art and performing art connect for you?

AC: I started doing collage in college, doing college radio, to make flyers for different events. It was one of those things of like, organizing events and no one was making flyers, so I gotta make the flyers. I don’t draw or anything like that so I started doing collage. Stuff I was making started being kind of comedic and I started having fun actually doing it. Getting different physical stuff to draw from was really fun, like looking for source material, and then I started to do it more seriously. Once I started playing music, it seemed like a natural extension of that. If I’m making this, might as well have it be a full aesthetic. And I know I can make something that would match it in a way that I could like. I like being able to control the whole, overall aesthetic of a release. So yeah, it felt like a natural extension. I’m making visual art, I’m making music, I want to release stuff, I should make art with it. Now I like the unified aesthetic that I feel like I’ve been able to do over time, which didn’t start out super intentionally but now I feel like I have it down, I think more about it in terms of extension across the different releases. Visual aesthetics are so important in music. I think about Impulse! Records, FMP, Blue Note, the graphic design’s so amazing. The early punk stuff too. I just love that aspect of music too, flyers and all that. Basically got into it as, “Who else is going to do it? Might as well be me!”

HB: You have such a distinctive style too. I look at the covers and I can tell that you crafted them.

AC: Thank you, that’s rad.

HB: I also find album covers really important. They say, “don’t judge a book by its cover,” but…

AC: Yeah, but that’s complete bullshit!

HB: It is!

AC: It definitely sets the tone right off the bat. How many of your favorite records ever, that you listen to all the time, are you like, “Oh, that cover’s not great? This is one of the best albums ever made but that cover’s not great.” I’m sure there’s examples, but I feel like all of my favorite stuff also has amazing visual aesthetics too.

HB: I also feel like when I’m in the mood to take a chance on a record, and it’s something I don’t know, I’m much more likely to grab something that is eye-catching right off the bat. Because that’s the first thing you see. You can’t hear the music yet, you maybe get a little hype sticker or something to describe it, you’re in a certain genre section. I’ll usually grab something that really catches my eye. And when it comes to physical media that’s a huge part of it as well.

AC: Oh yeah. There’s a guy in St. Louis who’s a good friend of mine, Jeremy Kannapell, he does all the booking for New Music Circle, and he’s a musician too and visual artist. When I moved to St. Louis, before I met him – and he still does this – he would make these flyers for shows that were just insane. He’d have a streamlined version of the flyer that’d be all analog, printed kind of screen-print style with the collage and illustrations. And then at this one local record store, he would have a different version of the flyer that would just be at that record store that would take up a giant chunk of the wall, with all these different components attached together. The flyer itself was this collage. He was booking all these experimental acts, and I didn’t know the names, they were all regional, DIY things – I’d just moved to town, I don’t know what any of this is. But anytime I’d see his flyers, it was really clear this was made by the same person, right off the bat the aesthetics are so uniform, it’s amazing! It became one of those things where it was like, what he was booking was great, but it also had this complete package where it’s like, anytime I saw one of those in the wild, I knew the show was going to be good because it’s falling under this umbrella. I feel like that is so important and I feel like people sleep on that aspect of things in this heavy, social-media-to-book-shows era that we’re in. And there’s still ways to do that online, but I still think the stumbling across something in the wild, the “What is that? This looks amazing,” is still important.

HB: Exactly. And I think it does kind of transfer to social media. In the physical realm, you’d want a flyer that’s going to capture someone’s eye in a bulletin board that’s cluttered with stuff. You want something that’s going to grab someone’s attention. I feel like social media, in a way, is the same. You’ve got so much stuff on your feed, what’s going to capture your attention?

AC: And now it’s just endless. (laughs)

HB: The feed that never does end. So, a couple final questions. What can people look forward to for your show at Torn Light?

HB: The feed that never does end. So, a couple final questions. What can people look forward to for your show at Torn Light?

AC: I think I’m going to do a solo acoustic thing for sure. I will have amps with me from playing with Mark in Chicago that week. I think I’m going to do an acoustic piece, an electric piece. Two improvised things, I think that will be cool. I’ve been trying to think about how to, in a solo live, span a bunch of the stuff that I do. I might start doing that more, it always feels good when I’m able to do that. If you liked the Two For Olivia tape, I think you’ll like the show. Try to bring both of those flavors.

HB: And then also, in the next few months, the rest of the year, what’s up next for you?

AC: Lots of recordings. In this time not playing live as much as I used to, I’ve been recording a lot of stuff with different people. I have a lot of collab stuff in the pipeline with folks that I’m excited about. Immediate stuff, I’ve got a tape that comes out June 17th that’s a harsh noise violin tape that’ll be out on Orb Tapes. Cool little label. I’ve got a second LP with Mark Shippy that should be out end of this year, early 2023. Vinyl’s kind of insane right now, so we don’t know yet. Everything was submitted a long time ago but we’re still waiting to hear back where that’s at with pressing. That will be great, I’m really excited about that record. I just recorded a bunch of stuff that should be out, I’ve got a trio with Patrick Shiroishi who’s an amazing sax player, and then Thom Nguyen who’s a fantastic drummer, he’s half of Manas with Tashi Dorji. We’ve got a trio tape that will be out I think fall of this year on Astral Editions, which I’m really excited for. I’m working on a trio recording with Lisa Cameron and Damon Smith that will be out on my own label soon-ish, in the next couple of months. I’ve got a duo with Damon Smith that we finished that should be really cool. I’ve got a quartet with Sandy Ewen – she’s a guitar player in New York who’s fantastic – it’s her, Damon, and Lisa. That’ll be out sometime. And then, I’m going to record with Weasel Walter from The Flying Luttenbachers and a guitar player in Kansas City, Seth Davis, along with Damon. We’ll be doing that in July and then that will get released at some point. Just lots of collaborative stuff down the pipeline, which I’m really excited about. I put out so much solo stuff in the last couple of years just because of being trapped at home. I’m excited to put out a bunch of group stuff. That’s my favorite.

Suggested donation for Alex Cunningham on Saturday, June 18th is $10-12, $7 for students.

In Stock

Alex Cunningham, As Slow as the Stream

Alex Cunningham, Two For Olivia

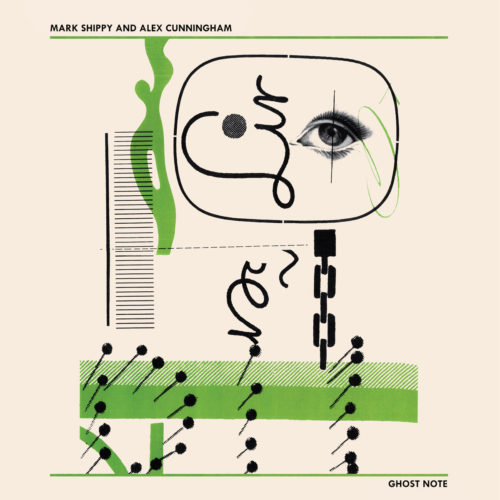

Mark Shippy and Alex Cunningham, Ghost Note

– Hannah Blanchette

June 16, 2022 | Blog