Go Undetected: Data, Music Listening Habits, and the Indispensable Value of Physical Records

There were a few intertwining threads in my life the past couple weeks that led to this rumination on the subject of music listening as data and surveillance, and how our listening habits can become shaped by that data. The seemingly disparate threads — reading Philip K. Dick’s A Scanner Darkly, purchasing a Timex watch, and listening to my favorite Oneohtrix Point Never record on my turntable — collided unexpectedly in my mind the other day, and the results will spiral out below.

I want to start with the Timex watch. For the past five years, longer than I’ve even been writing this blog, I wore an Apple Watch. Initially received as a gift, I came to embrace the watch’s features, which allowed me to leave my phone in another room and still received my texts and whatnot. The watch also notably included robust fitness tracking capabilities. The watch is so finely tuned to facts such as my heartbeat and speed that if I walk fast enough, it would automatically ask me if I’d like to track the walk as a workout. The more I think about it, the spookier it is. I’ve become increasingly irritated by the watch, its nuisances overtaking its perks. The other day, it dawned on me: I don’t really need my watch tapping my wrist the exact moment I get a text message. It is not necessary that I have all of this accumulated data about my steps per day, my heart rate, my calories burned. Why do I need data about my very own life, that I don’t even use? If I don’t use this data, who is? I placed the Apple Watch on its charger and immediately ordered a simple Timex watch. My wrist is now lighter and less distracting.

The watch incident could have passed by without any further thought, until I put my favorite Oneohtrix Point Never record on the turntable the other day. As the equal parts unsettling and gorgeous Russian Mind began to play, an unnerving thought crossed my mind: “This play of the record on vinyl will go undetected by my listening history.” Streaming and vinyl combined, I’ve spun Russian Mind more times than I could possibly count. But I don’t have to count! I could look it up on my Apple Music history right now. Every moment that I have pressed play on any track has been tallied, contributed to my Apple Music Replay (the Apple equivalent of Spotify Wrapped), and fed into the algorithm of my recommended listening. All of this data is available for me to review. But once again, the question returned to me: Why do I need all this data? I know what musicians I like, I have my own list of favorite records I can rattle off at a moment’s notice, I have a physical record collection that speaks to my journey with music far more deeply than a play count can.

I realized that physical and analog objects don’t demand for data collection in the same way that digital life does. One might make an inventory of their collections, alphabetize them and organize by genre, but the minutiae of their use is not for collecting. Something about digital life demands the collection of data, and a lot of this probably stems from how that same data “has” to be collected on us for advertising and marketing. We have been made to care about our data, when the act of listening to a record, reading a book, or going for a run should be enough to care about in and of itself.

As the year comes to a close, the annual tradition of sharing one’s Spotify Wrapped (or other streaming service equivalent) is upon us. The presentation of one’s top listening of the year via social media or discussion amongst friends is often framed as either a flex of a person’s impeccable music taste or a sheepish admission of the embarrassing number of times a particular song was in rotation. On the other side of the streaming service, bands will sometimes flaunt year-end listening statistics as well, paraded as markers of growth, progress, and popularity. The growing prevalence of these acts emphasizes how much we have been conditioned to care about our music data.

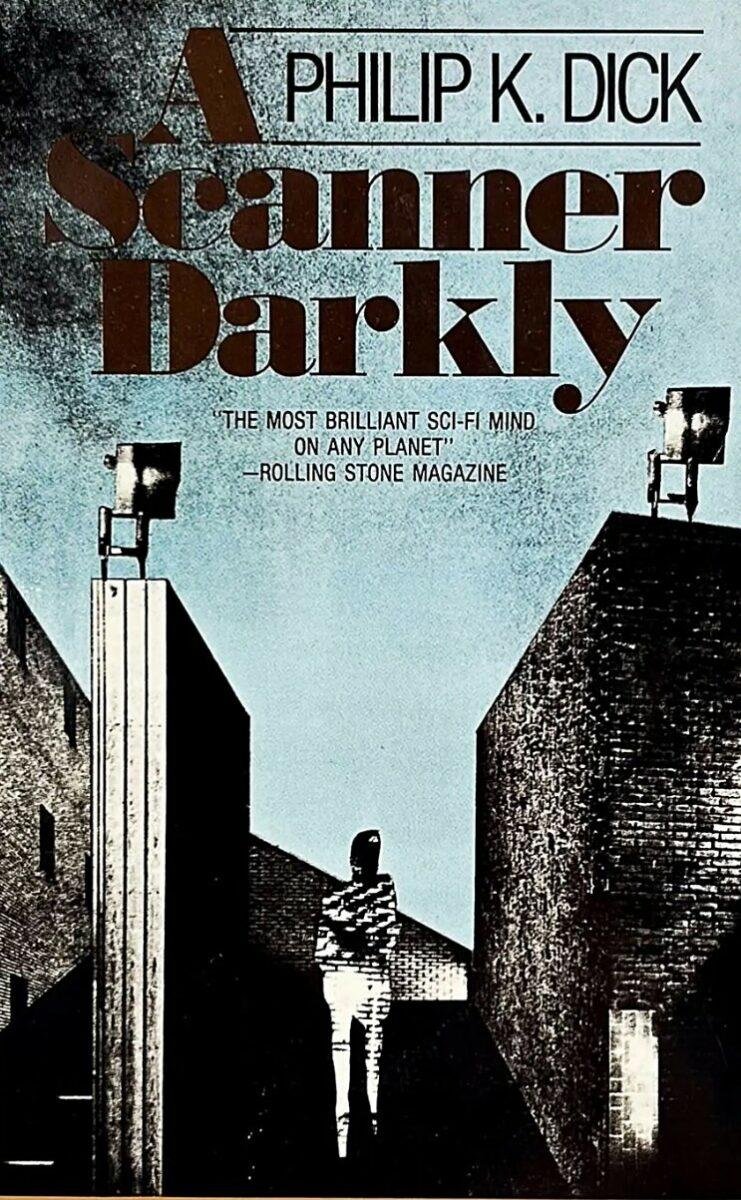

This facet of the relationship between digital music listening and data led to the final thread weaving itself in as I reflected on these topics: Philip K. Dick’s A Scanner Darkly, a book I had just finished reading a couple weeks ago. Often considered one of the most significant works by the science fiction author, A Scanner Darkly is set in a near future in which society is crippled by the deadly drug Substance D. Undercover agent Bob Arctor, who reports to authorities as the anonymous avatar Fred, is eventually assigned to investigate himself. Arctor/Fred is placed under heavy surveillance in his own home and is forced to watch the hours of footage of his every waking moment. He has to search for meaning and understand his identity through viewing his own interactions and habits, eventually becoming increasingly disconnected from the person on the screen and his own sense of self.

The book’s themes of surveillance and interacting with one’s own data came to mind when I thought about how we use the digital data collected about our habits and inclinations, specifically within music listening. If my social media landing pages around the last week of December are any indication, we have come to highly value the data collected on our listening habits through gimmicks like Spotify Wrapped. To what extent do we engage with this data, allow it to dictate aspects of our musical identities, and feed right back into the data again?

Apple Music users can save their top 100 played songs of the current year as a playlist starting in February. I perennially fall into the trap of saving this playlist and shuffling it when I’m too fried to pick out new music to play. Consequently, the playlist becomes a feedback loop with itself. I keep playing the top played songs over and over, causing them to solidify their status as top songs. Using this playlist also causes me to become stuck in a listening rut, passively engaging with my existing tastes rather than actively seeking out new records and musicians to expand my palette.

And while I don’t wish to come across as paranoid (although this subject may warrant a bit of healthy trepidation), it is worth considering how this data is not just for us. Our music listening on streaming services is surveilled. Each piece of data we see is the tip of the iceberg of what’s collected by these services to contribute to algorithms, advertising, marketing, branding, etc. To some degree, this isn’t a new concept. I am certain that record labels, A&R, and more have been collecting sales data for decades for these same purposes. But the average person wasn’t expected to care about music sales data, and each person’s individual play wasn’t recorded and sent off for analysis.

So digital life has turned every little digital action into data, which amounts to a large portion of the actions we take every day. Further, digital life has the potential to data-fy our personal concepts of music listening and musical identity. How do we resist the data framework for music listening? I’m probably preaching to the choir here, but listening to physical media is a huge step in the right direction. Putting the phone down, heading out to the record store, chatting with shop staff, flipping through a bin, gently placing a record on a turntable, shoving a tape into your exhausted Corolla, staring at the ceiling while you hear a record top to bottom, filing your record collection the way you see fit, all of these actions go “undetected,” but are more valuable than any Spotify Wrapped data could ever be. Each of these actions add a little piece to what your musical identity is, and involve you actively making choices to purchase this, say that, listen to that A-side, skip that B-side for now. You put your whole self into it, instead of having a computer tell you what you like after the fact. You don’t need that. You already know what you like. Grab that record off the shelf and give it a spin.

– Hannah Blanchette

November 17, 2024 | Blog