Experimental Folkways: Preserving and Innovating the World of Sound

Recently, I’ve been thinking a lot about Folkways’ experimental records. First, my interest was piqued with their recent release of Matmos’ Return to Archive on the label, which features the experimental electronic duo, along with contributions from Aaron Dilloway, reworking field recordings recorded on previous Folkways releases. Then, as I was reading David Grubbs’ Records Ruin the Landscape, I noted when he mentioned that John Cage and David Tudor’s Indeterminacy was released on Folkways. I’ve always known that Folkways has a history of releasing experimental records and many albums of field recordings. But I’ve never taken the time to contemplate the relationship between experimental music and one of the most well known folk labels in the world.

Moses Asch’s initial vision for Folkways was to “record and document the entire world of sound.” This goal has been accomplished through their recordings of music from across the globe and their collections of field recordings. However, a quick search of their catalog makes it clear that not every genre of music appears on the Folkways label. So why has experimental music been different? What does the continual inclusion of experimental records in the Folkways catalog say about the relationship between folk and experimental music, as well as the experience of recorded sound?

Experimental records on Folkways generally fall into three trends: albums of avant-garde and electronic music, experimental music that interacts with the natural world, and field recordings. The latter is not inherently experimental per se, but the process of collecting field recordings and arranging them on a record can evoke a sense of musique concrète for the producer and listener, crafting an curated, aural facsimile of a place. And of course, field recordings have had enduring significance for experimental artists who manipulate and collage, as evidenced in the new Matmos release.

Two collections of field recordings on Folkways have captured my attention because of their relationship to experimental sound, both recorded by Michael Siegel in 1964, Sounds of the Junkyard and Sounds of the Office. In my first post about Folkways, I briefly discussed Sounds of the Junkyard, a record which sonically depicts a Warren, Pennsylvania junkyard. So much of Sounds of the Junkyard includes timbres that are prescient of noise and industrial music. The first track, “Acetylene Torch,” could easily have been a nineties Merzbow track if I didn’t know otherwise. For Sounds of the Office, Folkways is incredibly self-aware of how its arrangement of office ambience such as an adding machine, vending machine, and addressograph, carries the quality of musique concrète. Of the time clock, they state its “banging and creaking…could be mistaken for a minimalist sound piece.”

Choosing to record spaces such as a junkyard or office may seem inconsequential, but the preservation of those audio environments has already proven valuable. Some of the machines in the 1964 office aren’t in use anymore, and the junkyard provided some of the most authentic industrial and mechanistic sounds that exist. Beyond the conservation of significant sounds in the American soundscape and elsewhere, Folkways’ field recordings emphasize the importance of ambient sound to the world of recorded sound as a whole. Composers of various forms of free and avant-garde music hear sound in the space around them as integrated with music, if not music itself, and Folkways’ dedication to compiling those sounds as albums enshrines their value.

Another recurring theme throughout the experimental records on Folkways includes experimental music interacting with nature, most apparent on records such as Jim Nollman’s Playing Music with Animals, Malcolm Goldstein’s The Seasons: Vermont – for Magnetic Tape Collage & Instrumental Ensemble, and Ann McMillan’s Gateway Summer Sound: Abstracted Animal and Other Sounds. Field recordings of nature alone are compelling in their own right, and Folkways has plenty of those in their catalog. But one step further, Folkways has appreciated artists who reconsider the relationship between human-made music and animal-made music, highlighting especially those who worked in collage and abstraction. On these records, the line is blurred so that contributions from humans, animals, plants, etc. are all considered as equal musical contributions from the natural world.

Goldstein’s composition aimed to “extend the sounds of the natural environment into the sound/space of human gesture” through a merging of magnetic tape collage and live improvisation. McMillan sourced the sounds of frogs and insects along with bells, gong, and harpsichord to create collages that abstracted an exact replicate of nature. And Jim Nollman worked in interspecies music, working to change human attitudes towards animals through making music with orcas, wolves, and turkeys. All of these approaches aimed to erode the boundary between naturally occurring sound and musical creation by human beings, as well as destabilize the idea of an exact representation of an environment. These goals could be considered in step conceptually with sound art and avant-garde compositions on other labels, bringing to mind the work of Alvin Lucier, Charlie Morrow, and Éliane Radigue.

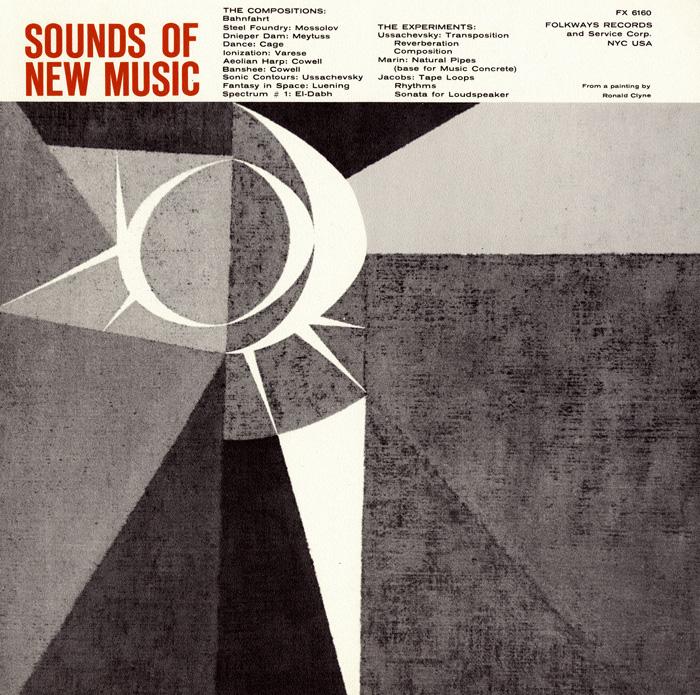

Lastly, a significant portion of Folkways’ experimental records throughout the years explored electronic, avant-garde, and computer music. Avant-garde composers such as Henry Cowell, Edgard Varèse, and John Cage appeared on 1957’s Sounds of New Music, innovations in computer music by Charles Dodge and Larry Austin were integral to Folkways’ early computer music compilations, and countless early electronic departments at universities contributed to compilations like the University of Toronto Electronic Music Studio’s Electronic Music in 1967. On the fringes of twentieth-century experimental music, groups like the Entourage Music and Theatre Ensemble released records on Folkways that brought together elements of modern composition, psychedelia, and folk.

This music is frequently the most academically-based, which may account for its inclusion on Folkways. Part of Folkways’ mission is music education, both for the public and through their production of formalized educational materials. Avant-garde and electronic composers of the mid-twentieth century garnered intrigue from both academic settings and members of the public, allowing them to transcend that boundary in a way that Folkways mirrors. However, I think the relationship between Folkways and experimental music goes deeper than this simple connection.

The relationship between folk and experimental music has been on my mind a lot this year, the concept recurring in my listening and my conversations with people. Alex York and I discussed the relationship between folk and minimalism at length when he was in the process of releasing his CD, Black Tupelo. Doesn’t it make perfect sense that a label that releases folk music also released Indeterminacy? There is freeness and indeterminacy in an old time jam for instance, never knowing how long you’ll play for, which verses people will sing, etc. A jam on one song can go for five minutes or twenty or more.

Furthermore, there is an element of human curiosity and exploration embedded into every second of experimental music that aligns perfectly with the broad range of musical styles which Folkways embraces, especially folk music. Field recordings not only record the entire world of sound, but also provoke questions about what music is, what sounds are worth preserving, and how we position ourselves as listeners to our environments. Composing music intertwined with nature, or creating interspecies music, realigns human relationships with nature, embraces nature as an equal collaborator. Lastly, avant-garde music removes itself from the constraints of predetermined rules of melody, harmony, rhythm, texture, and instrumentation, favoring indeterminacy, freeness, atonality, interruption, and/or ambience. There is a freedom to both folk and experimental music that anyone who has performed or listened to either has experienced. Folkways’ embrace of experimental music is essential to preserving the world of sound, as well as its future innovation.

– Hannah Blanchette

December 21, 2023 | Blog