-

×

Villa Abo - Carpet Proof Of Daily Reports

1 × $9.00

Villa Abo - Carpet Proof Of Daily Reports

1 × $9.00 -

×

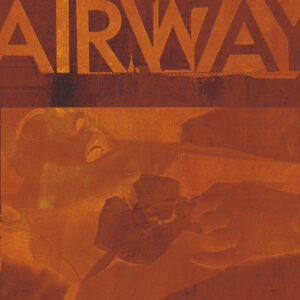

Airway - Live At Zebulon

1 × $9.00

Airway - Live At Zebulon

1 × $9.00

Subtotal: $18.00

Several years ago, NPR published a piece on the ever elusive nature of the pedal steel guitar, an instrument nearly fettered to the “classic mid-century Nashville sound,” despite its potential for so much beyond one or two genres. The article reflects on the musicians who have taken the instrument down unorthodox paths, collecting statements from figures such as Jim O’Rourke and Chuck Johnson. O’Rourke felt that the pedal steel guitar exists in the boundary between acoustic instrument and synthesizer, which “only reinforced [his] love.” Johnson said, “I don’t think you can overstate the importance of the fact that, when you ask who’s pushing the instrument forward, the answer is there are these two women — Susan Alcorn and Heather Leigh. More than any other instrument I know, the culture around [pedal steel] is so male dominated.” Sadly, today’s blog is here to say farewell to one of those innovators. Alcorn passed away last month at the age of 71. She was known for combining country and western styles with free improvisation on the pedal steel guitar, carrying the instrument out of its comfort zone and into the whirlwind of the avant-garde. The unorthodox path she charted with the pedal steel guitar will hopefully continue to be trodden by those she inspired to toss aside the confines of genre.

Often confused with its sibling, the lap steel guitar, the pedal steel guitar is an incredibly complex instrument that proves difficult to get started with due to its high price point and complicated mechanism. The pedal steel is operated by pedals and levers using hands, feet, and knees, and it can be played in various standard tunings. While the pedal steel guitar is most often associated with country music, such as on Ernest Tubb’s “Half A Mind (To Leave You)” featuring George Jones from 1957, the instrument’s boundaries would start fraying at the seams by the early 1980s. Brian Eno implemented a pedal steel guitar for his soundtrack for the documentary about astronauts, For All Mankind. On the accompanying 1983 record, Apollo: Atmospheres & Soundtracks, you can hear how Eno evoked the country records that the astronauts took with them into space by interweaving the pedal steel guitar into his ambient landscape. Fast forward to decades later, and Susan Alcorn’s 2007 album, And I Await the Resurrection of the Pedal Steel Guitar, was a prophecy, the channeling of a vision into a reality that Alcorn then manifested herself.

Alcorn’s musical background began in childhood, encouraged by the musicians in her family. Her mother was a pianist and singer who performed with the Cleveland Symphony Orchestra. When Alcorn was young, she would crawl under her mother’s piano to hear her play. In a 2010 interview with The Quietus, she recalled, “As a small child I’d sit under the piano, letting the sounds wash over me while my mom was playing, and sometimes I’d reach over and push on one of the pedals; I guess that was my first musical instrument – the sustain pedal of a piano.” Alcorn began playing the guitar at twelve-years-old, accompanying her admiration for blues guitarists like Muddy Waters and Son House. While hearing John Coltrane’s OM for the first time at sixteen radically shaped her taste in music, her interests were ultimately expansive, ranging from The Supremes to Sun Ra to Ornette Coleman to John Cage. She even remembered occasions when she was left home alone to her own devices, and she would dance along to an Edgard Varèse record. It only made sense that a person this musically omnivorous would go on to make music that was equally as heedless to categorization. Like she told The Quietus, “I’ve always loved music that was left field and have always been fascinated by extended technique; this pre-dated my interest in the pedal steel guitar, and it never left me.”

It wasn’t until 1975 that Alcorn first gravitated to the pedal steel guitar. She became transfixed by the instrument after hearing it played in a nightclub. Alcorn stated on her website, “I remember that wondrously magical metallic sound and the way the shining steel bar seemed to float over the top of the instrument. I was hooked.” The spaces between the notes, especially on fretless instruments, fascinated her as well. The logical next step for Alcorn after acquiring a pedal steel guitar was to join country and western bands, where she hoped to gain insights into the technique. However, the feedback was often negative, with Alcorn constantly facing critique for not approaching the instrument with the correct technique. She took this criticism in stride: “There’s a lot of self-discipline and respect for the roots that goes into developing and holding onto that shared language, and there’s beauty in it like there’s beauty in any language. However, not everyone fits into that mould which is good also – they help the music to branch out and grow. I guess I fit into the latter category; I couldn’t play things the same way every time.” In 1981, Alcorn moved to Houston and continued to play in country and western groups while expanding her approach through studying jazz improvisation with Dr. Conrad Johnson.

The nineties brought a couple major events in Alcorn’s musical journey that impacted her path forward as a composer and performer. In 1990, Alcorn met and befriended the electronic composer Pauline Oliveros, who introduced her to the practice of deep listening. Alcorn’s definition of deep listening versus simply hearing clearly denotes the distinctive quality of the practice: “Hearing, of course, is, for most of us, natural, but listening is something we can cultivate – be conscious and attentive of the sounds around you – the wind in the trees, the traffic, your daughter in the next room brushing her teeth, the traffic, your fingers tapping on the keyboard.” While deep listening laid the groundwork, her first live improvisation in 1997 was the ultimate catalyst. The trombonist David Dove asked Alcorn to perform a live improvisation set, which she was entirely unfamiliar with. Alcorn walked onstage with nothing planned, and found herself transformed in the process. “To me, free improvisation is a liberating experience, and it can be an invigorating experience to listen to, if the musicians performing respect the music and the audiences they play for,” she stated.

Alcorn released her debut solo album, Uma, in 2000, introducing the world to her woozy, mysterious, and idiosyncratic realm for the pedal steel guitar. Her pieces on her albums are at times an insistent drone, others a plaintive melody, and at turns disquieting clusters of atonality. There are moments of stark, aching consonance and others of gnarled, frenetic dissonance. Alcorn also developed a reputation for her interpretations of works by twentieth-century composers such as Astor Piazzolla and Olivier Messiaen. She had spoken highly of the latter in particular, stating, “Bird songs, gamelan, pastoral, carnatic – there’s a majestic sense of mystery, wonder and ecstasy in his music. The chordal structure – consonance mixed so elegantly with dissonance, movement in major thirds, complex and very organic-sounding rhythms – beautiful.”

In my research preparing for this post, one quote from her Quietus interview (a fantastic interview which I am grateful exists, as I found many of her responses perfect for this post) struck me in particular, “Every note, every musical sound and every instrument is alive. I try to give each of these room to breathe. My pedal steel guitar is a co-creator, in every sense of the word, with its own voice, so I try to give it space to tell its story. Also, for the notes, if you give them space, then they can begin to tell their story too. You can hear it in all the subtle inflections and in the universe of harmonics interacting with harmonics.” I read these words and immediately wanted to name the article, “Every Instrument Is Alive.” If we embrace Alcorn’s belief that every note is alive, then her presence in our world continues on, resonating with each second of her music that enters the atmosphere.

– Hannah Blanchette

February 28, 2025 | Blog