-

×

Barry White Promo Photo

1 × $8.00

Barry White Promo Photo

1 × $8.00

Subtotal: $8.00

Coming from a background of studying music history in graduate school, and assuming teaching responsibilities as part of that program, I perked up when I read that Smithsonian Folkways has developed their own publicly accessible educational courses titled Smithsonian Folkways Music Pathways. Just launched at the end of January, the series provides extensive courses on specific topics intertwined with the Smithsonian Folkways catalog, with a focus on “lesser-known corners of music history.” At this moment, there are two pathways available, Estoy Aquí: Music of the Chicano Movement and Cajun and Zydeco Music: Flavors of Southwest Louisiana. They have plans for a third course to be introduced about women and the blues. For this week’s blog, I explored Estoy Aquí to get a basic feel for the materials and how they function as lessons for solo, adult learners. The more I reflected on Estoy Aquí, the more I considered how vital resources like Smithsonian Folkways Music Pathways are to this country more than ever, and how advocating for publicly accessible educational materials is central to preserving not just folk music in the United States, but also the very sense of what American identity is.

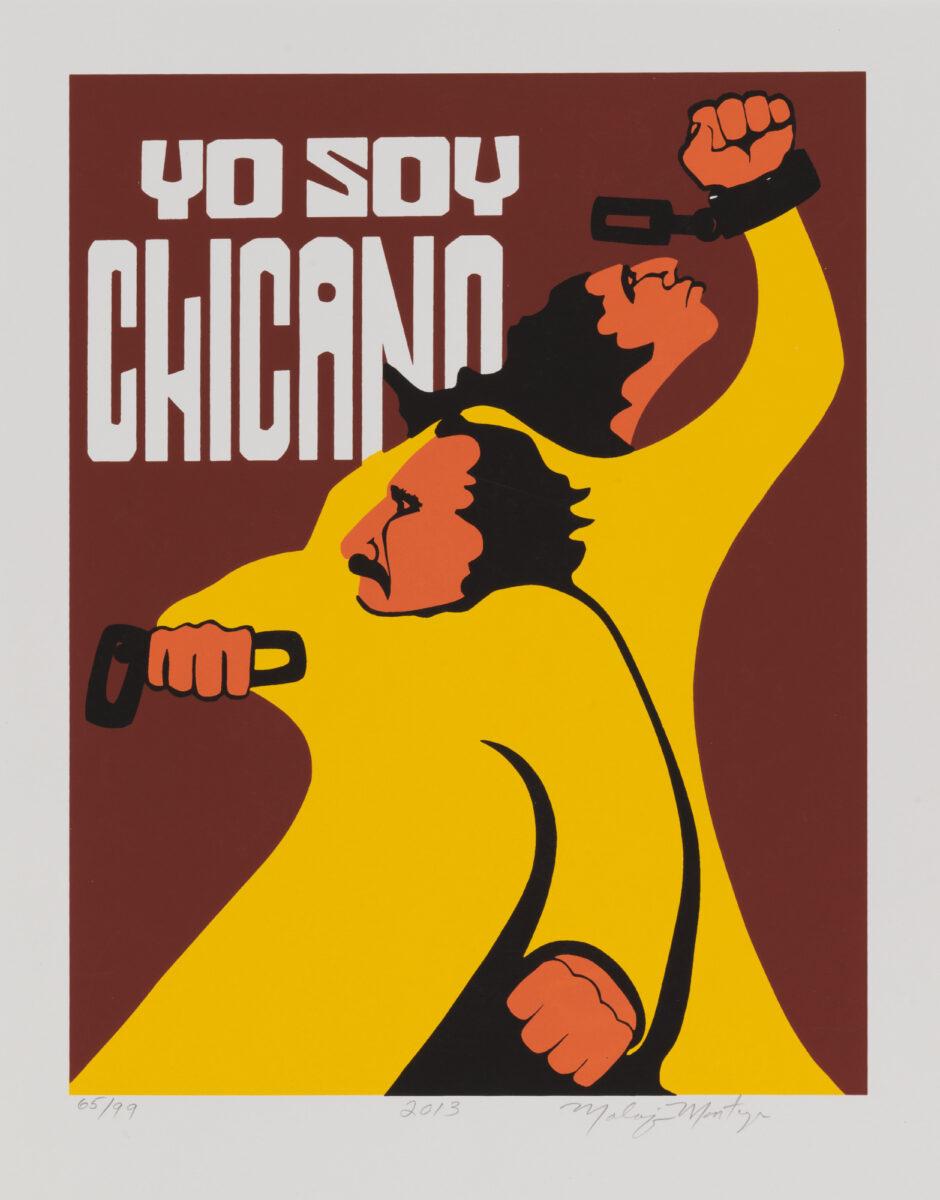

Estoy Aquí is a pathway devoted to the Chicano movement, which spanned the late 1960s through the 1970s and advocated for “fair wages, safe working conditions, land rights, educational opportunities, and political representation” for Mexican-Americans. Figureheads such as César Chávez, Corky Gonzalez, Dolores Huerta, and Reies López Tijerina were instrumental to the progress of the movement, and Estoy Aquí connects their stories with the music that emerged from the Chicano movement and vocalized the sentiments of Mexican-Americans fighting for equality in the United States. I interpret the term pathway as an analog to course, and Estoy Aquí offers the same breadth and depth as a course on music and the Chicano movement. The pathway is divided into twelve lessons, and each lesson contains three sections that provides approximately 20-30 minutes of material. Estoy Aquí covers the history of the Chicano movement and identity, historical precursors to the movement, current ripple effects of the Chicano movement such as the rasquachismo art aesthetic, and of course various genres of Mexican/Mexican-American music such as corridos, conjunto, música norteña, mariachi, and tejano.

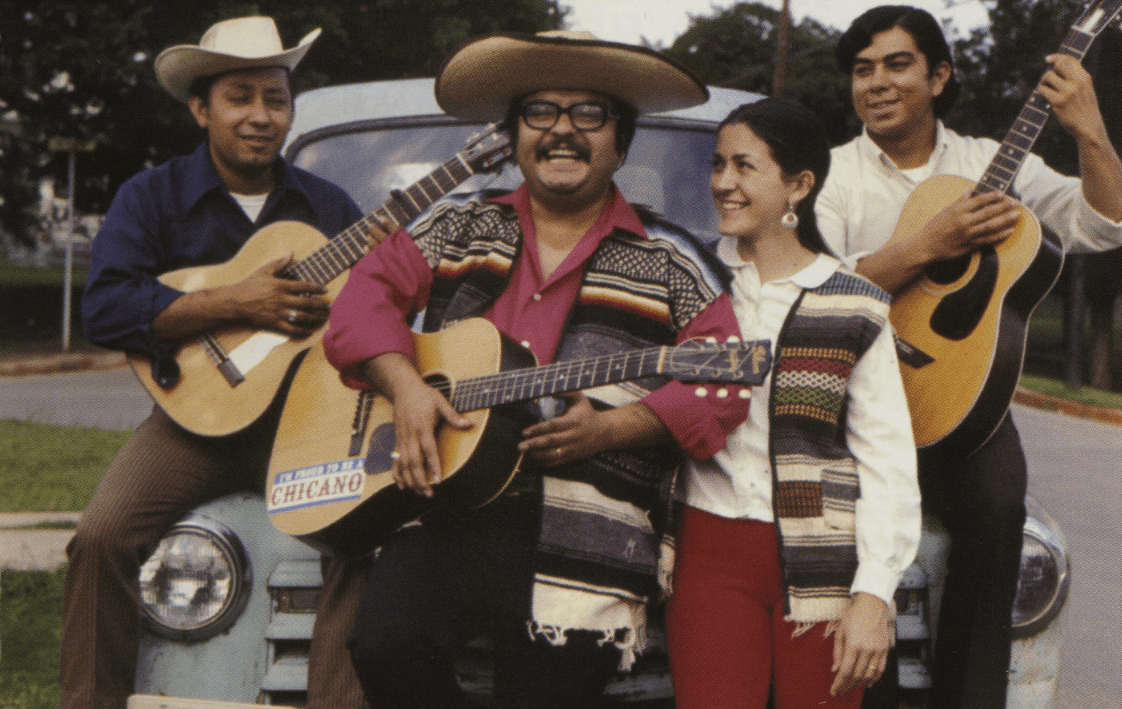

Although the Pathways are certainly designed for use by educators primarily, Folkways also emphasized that while they are “designed with national education standards in mind, they are also perfect for independent and lifelong learners, as well as anyone interested in learning more about the histories behind their favorite LPs released by Smithsonian Folkways.” The presentation of the material still follows a structure that is familiar to classroom settings, which can take a little getting used to as a solo learner. The Pathways are presented as slides, which contain information along with visuals, audio, and video. One of my favorite aspects of the slides was the emphasis on the Smithsonian’s archives, like the fantastic photographs and examples of archived objects, such as an accordion signed by Flaco Jiménez that resides at the National Museum of American History. Implementing these resources in the lessons provides a sense of rigor and authenticity to the information presented. These lessons also allow for the music and art traditions to speak for themselves on the topics. In the first lesson, the concept of the Chicano/a identity is shaped through the song “Chicano” by Rumel Fuentes and Los Pingüinos del Norte — heard through recording, captured in photography, and depicted in the seminal 1976 documentary, Chulas Fronteras by Les Blank and Chris Strachwitz.

There are some aspects to the Pathways that are especially appealing to an adult, solo learner that can enhance the experience and provide more depth. Each slide is accompanied by speaker notes, that are intended for use by a teacher to guide a classroom. I find that these speaker notes often establish context and detail that round out the lesson, and I would recommend to anyone wishing to try one of these Pathways on their own to have the speaker notes turned on for additional insights into the material. Another bonus for adults is the bibliography hidden under the “More +” button on the landing pages for each lesson. Folkways curated a detailed bibliography of books, articles, websites, records, videos, and photographs that can serve as additional reading, listening, and viewing for anyone who wants to fully immerse themself in the topic. I think the bibliography is the most useful resource for adults, who can use the slides as a introduction to the topic before encountering the vast literature available.

It is important to note that while the Pathways slides and teacher’s supplements are crafted with traditional classrooms in mind, and that these slides can be adapted for solo use, there are also a multitude of other learning spaces that these materials can be used for. Public library programming and community activist groups, for example, could bring these lessons into public spaces and present accessible educational opportunities for adults while maintaining a group atmosphere. Groups of friends could even decide to work on the Pathways together for an even less formalized approach. The essence of crafting accessible educational materials is that they are flexible enough to fit a variety of circumstances without losing a sense of academic diligence, which I believe Folkways captured here. The fact that these courses are free, completely accessible from a web browser, and open to both solo and group study injects me with a hope that there is still an imperative to create stimulating learning opportunities that extend beyond formal institutional walls.

I am elated that Folkways is putting together these educational materials that are accessible to the public, especially lessons that highlight the musical traditions of communities in the United States that are historically and currently marginalized in policy and in representation within historical narratives. In the wake of massive cuts to federal funding, especially to diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives, it is incredibly bold of a record label associated with the US government’s largest educational institution to explicitly advocate for the relevance of these musical traditions to the nature of who we are as a nation. Educational institutions in the US, which are not only universities, but also museums, libraries, and organizations like Smithsonian Folkways, are facing threats to what they contribute to the fabric of this country: encouraging curiosity and openness to learning about the full breadth of the American experience, an experience that is not singular to one person, one community, or one ideal.

The Estoy Aquí Pathway makes it clear how essential the Chicano movement was to the history of folk music and the US, and to the continuing work that needs to be done to establish equality for Mexican-Americans. The fight is not over, and understanding that history is one piece to continuing the legacy the Chicano movement established. As a fan of Folkways, I’ve discussed the label numerous times in the blog, and I have often emphasized founder Moses Asch’s original vision to “record and document the entire world of sound,” which I believe captures the essence of what makes Folkways so unique: that idea that every sound is special, from the croaking of a frog, to the electronic warbles of the University of Toronto Electronic Music Studio, to a corrido by Rumel Fuentes. The entire world of sound is worth preserving, no exclusions. We have to continue to advocate for that mindset going forward in everything we fight for, musical or not. It is that openness that won’t just preserve sound, but will preserve who we are.

– Hannah Blanchette

February 16, 2025 | Blog