Documenting a Third Place: The Continuing Relevance of Ernest Hood

About a month ago, I selected Ernest Hood’s Back to the Woodlands, an archival release from last year, as my weekly staff pick. I found myself lulled by its gentle blend of ambient music and environmental sound as I myself was embracing some coastal beauty on vacation. Hood has sat in the back of my mind for years as a compelling individual who unintentionally developed a reputation as an ambient and experimental pioneer. As far as I can see it, Hood’s goal wasn’t to push the boundaries of music, but he simply had an open mind about what was worth putting on a record. That open mind is what I believe is influential about his music after all these years, as well as its current role in reflecting on sound, memory, and society.

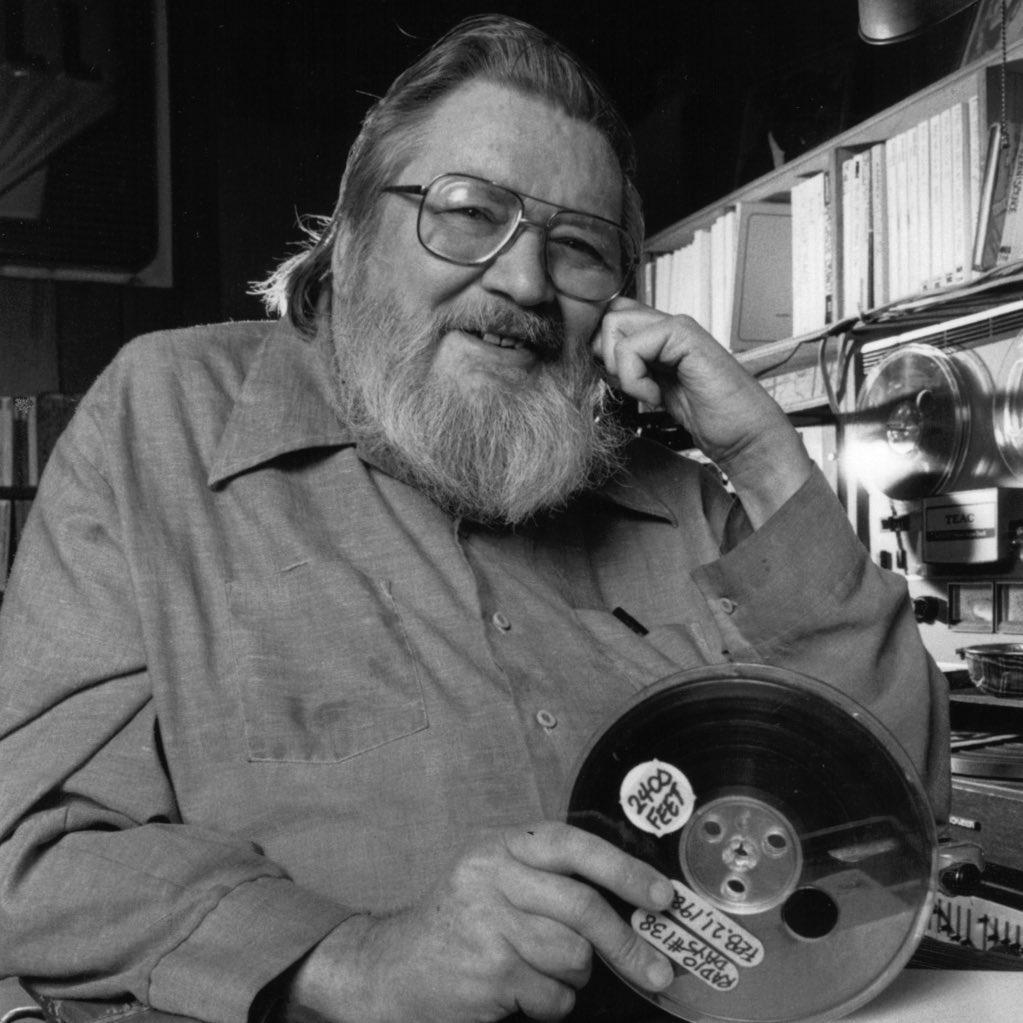

Initially a jazz guitarist, Hood contracted polio in his late twenties and could no longer play guitar. He then took to the zither, an instrument that would become a defining element of his music. The zither shares a lot sonically with the harp, but with an airy quality to its tone that gives it a dreamlike, floating presence.

At the start, music was not the primary focus of Hood’s recordings. Hood initially put his efforts into recording what he called “travel tapes” with his wire recorder, something we would definitely recognize as field recordings. He went on excursions around the greater Portland area, recording the aural environments of various places, spanning nature, country stores, and covered bridges. While there, Hood also drew the location he visited. Afterwards, he transformed these recordings into “travel tapes,” which were intended for the disabled and those who could not leave their homes. The travel tapes were meant to capture the ambient environments of the outdoors for those who could no longer go to those places.

Hood had a particular fascination with suburbia, especially childhoods spent in suburbia, which eventually manifested in his sole, private press LP, Neighborhoods. Simon Reynolds stated in an essay for The Nation that the album was a “gorgeously tender sound-portrait of the all-American suburban idyll.” Released in 1975, the record centered around field recordings of suburban neighborhoods in the Portland area, accompanied by musical compositions on zither and synthesizer. Hood considered each track on Neighborhoods as “musical cinematography,” meant to capture the essence of a certain place in a similar way that filming it would, and similarly transporting a listener to that place. Most of the LPs were given away to friends, and would pop up in Portland record stores periodically over the following decades. Jed Bindeman, co-founder of Freedom to Spend, came across the record in stores throughout the years, inspiring the label to reissue it for the first time in 2019.

Beyond simply creating a sonic document of a suburban space, Hood relayed a clear message with his record about the social aspects of the album. While he acknowledged that Neighborhoods is not social in the sense that it could be put on at a party, he wrote in the liner notes that “it is a social record in that it reminds us of the fact that most of us made our first social contacts…in our neighborhood streets.” With this statement, Hood’s definition can be expanded beyond the traditional view of a suburban neighborhood. Neighborhoods can crop up on specific city blocks, within stretches of farmland, and everywhere in between.

Hood’s work also elicits insights into the relationship between sound and memory. In the liner notes for Neighborhoods, Hood shared how neighborhoods “played such an important role in the formation of comfortable memories.” Reynolds deftly made the connection between Hood’s synth sounds and childhood memory, stating, “The charmingly dated synth is redolent of 1970s PBS, while each listener will affix personal memories date-stamped to the period of their own childhood years and linked to their hometown in other states or countries.” He also discussed the relationship between privilege and public vs. private spaces, as well as how smartphones have shifted our sense of community to be less geographically based.

A couple months ago, I reflected on the concept of public memory here at the blog, and I think the sounds of suburbia depicted on Neighborhoods exist in a space somewhere between public and private. A neighborhood could even be considered a third place, a location outside of work and home where people socialize and form community. Another angle with which to analyze the yearning and nostalgia experienced while listening to Ernest Hood’s albums is from the vantage point of a society with a decline in third places, or at the very least, a decline in their use.

Third places have been a topic of interest of mine for a little while now — I’ve got Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community on my to-read list and my YouTube algorithm is now flooded with recent videos on the subject. While some types of third places still thrive, such as cafes, others have experienced hardship as life continually moves online, like brick-and-mortar stores. Hearing Hood’s soundscapes of ambient, social sounds that exist outside of our work, homes, and online lives can create a longing for that type of connection with others that is based in being physically present with one another. Hood’s records have the versatile ability to both bring the outside world into the living room, while also encouraging anyone who can to step out and tune into their surroundings.

– Hannah Blanchette

October 2, 2023 | Blog