“Disqualify Me”: The Musical Innovations of Tropicália

Caetano Veloso and Gilberto Gil take the stage at Brazil’s Festival International de Canção songwriting competition in September of 1968. The crowd of students is contentious. Veloso shouts to the audience, “So, you’re the young people who say they want to take power! If you’re the same in politics as you are in music, we’re done for! Disqualify me with Gil. The jury is very nice, but incompetent. God is on the loose!” They were further booed off the stage with shouts and objects thrown at them.

There is a lot of context and events that surround this one moment in tropicália’s year of musical innovation in Brazil 1968. This week, we take a brief look at the complex history of this Brazilian artistic movement that upended tradition and challenged authorities. Despite tropicália’s extremely brief period as a musical movement, its impact on history extends far beyond the late 1960s and early 1970s.

Tropicalistas adhered to a concept referred to as antropófago, or “cultural cannibalism,” which encouraged creating new artistic forms by blending disparate traditions. This could be seen in tropicália’s various artistic manifestations: music, visual art, film, and theatre. The music of tropicália brought together traditional Brazilian genres such as samba and the emerging sounds of American and British psychedelic rock, manifesting a sound that was innovative and flouted tradition. As bossa nova was one of the biggest Brazilian musical phenomena in and outside of the country’s borders during this time, tropicália’s radical redefining of Brazilian sound brought a lot of criticism. Some artists feared the influence of American and British rock on Brazilian traditions.

Furthermore, tropicália’s musical innovations combined with lyrical critique of government censorship brought attention to the tropicalistas from the Brazilian government, a military dictatorship at the time following a coup d’état in 1964. Incendiary events such as the murder of three protestors by the military in 1968 gave even more political weight to the music tropicalistas created.

The tropicália movement as it existed in the late 1960s ended under drastic circumstances. Fearing the power and influence of tropicalistas, President Costa e Silva signed into law the Ato Institucional Número Cinco (Fifth Institutional Act), which permitted government censorship of art, film, theatre, music, and the press. Caetano Veloso and Gilberto Gil were among the first individuals targeted by this act. They were arrested, placed in solitary confinement for two months and then under house arrest, before being exiled to England in 1969.

Many mark the beginning of musical contributions to tropicália with Caetano Veloso’s second, self-titled album, released in March 1968. The album contains a track titled, “Tropicália,” which referred to another seminal work in the tropicália movement, Hélio Oiticica’s art installment from 1967 of the same name, that played upon Brazilian stereotypes. Both Oiticica’s installment and Veloso’s record solidified the artistic characteristics of tropicália. Veloso accomplished this in the track “Tropicália” through references to Brazilian culture with an offbeat, orchestral sound.

Songs such as Veloso’s “É Proibido Proibir,” are also prime examples of the revolutionary power and subsequent disdain tropicália could garner. “É Proibido Proibir” directly criticized government censorship implemented by the military dictatorship. Veloso recalls in his memoir Tropical Truth (1997) his experience performing the song with Os Mutantes backing at the Festival International de Canção in 1968. He wrote, “The hatred…on the faces of the spectators was fiercer than I could have imagined.”

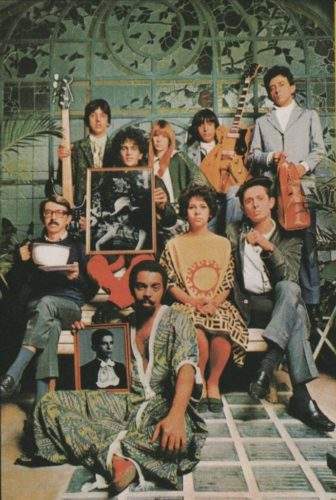

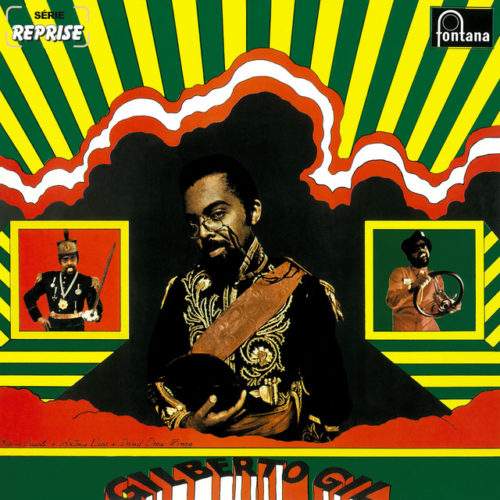

Gilberto Gil (1968)

Another major figure in tropicália was Gilberto Gil. Akin to his peers, Gil’s music combined elements of music from across the globe. This blending not only reflected an amalgamation of global cultures, but also represented Gil’s views on Brazilian culture that he adapted from poet Décio Pignatari’s concept of “Geléia Geral,” or “General Jelly.” Brazilian culture as fluid, contradictory, both local and global.

The most distinguished band to emerge from tropicália was Os Mutantes, whose original lineup included musicians Rita Lee, Arnaldo Baptista, and Sérgio Dias. Os Mutantes brought together Brazilian and psychedelic traditions seamlessly, while also experimenting with avant-garde techniques. The group would also provide backing for many of the tropicálistas, like Veloso and Gil. Beginning with their self-titled record from 1968, their music was catchy and experimental, from the guitar and melody hooks of “A Minha Menina” and “Bat Macumba” to the musique concréte-like opening of “Adeus Maria Fulô.” Their visual aesthetic captured the essence of tropicália as well, with bright colors and designs inspired by Brazilian, American, and British influences.

On Os Mutantes, the band includes the song, “Baby,” an iconic song of tropicália. However, the most iconic rendition may have to go to Gal Costa. Although Costa was already collaborating and performing with other Brazilian musicians before her involvement with tropicália, her self-titled record from 1969 is her album that remains a tropicália classic. Gal Costa houses her version of “Baby,” her smooth, echoing voice accompanied by lush orchestral arrangements.

Perhaps the defining musical document of tropicália is the album Tropicália: Ou Panis Et Circensis, a collaborative album released in 1969 which featured many of the great talents of tropicália: Gil, Veloso, Os Mutantes, Costa, and Nara Leão. Combining tracks from each of these artists’ records, along with collaborative performances, Tropicália: Ou Panis Et Circensis captures the spirit of tropicália and provides a roadmap for anyone interested in diving into the movement’s musical offerings. We recently stocked 2022 represses of Tropicália: Ou Panis Et Circensis, one as vinyl only and another as vinyl & CD, so buy a copy if you would like to gain a sense of the defining tropicália tracks and musicians.

Resources

Andy Beta, “God Is on the Loose! How the Tropicália Movement Provided Hope During Brazil’s Darkest Years,” Pitchfork (2016)

“Brazilian Tropicalia,” PBS

Ramsay Lewis, “Tropicália: The Most Important Musical Movement You’ve Never Heard Of,” Pimsleur

Matt Ryan, “An Introduction To Tropicália,” Strange Currencies Music (2021)

“The Story of Hélio Oiticica and the Tropicália Movement,” Tate

“The Story of Tropicália in 20 Albums,” Pitchfork (2017)

“Tropicalia: A Brazilian Revolution in Sound,” Soul Jazz Records

“Tropicalia – Revolution in Sound,” BBC World Service (2016)

Products

Caetano Veloso, S/T

Mutantes, Ao Vivo (note, a later iteration of Os Mutantes with only one of the original members)

VA, Tropicalia: Ou Panis Et Circensis (also available as a vinyl & CD version)

– Hannah Blanchette

April 3, 2022 | Blog