-

×

The Isley Brothers Promo Photo

1 × $8.00

The Isley Brothers Promo Photo

1 × $8.00 -

×

13th Floor Elevators – Easter Everywhere

1 × $17.00

13th Floor Elevators – Easter Everywhere

1 × $17.00

Subtotal: $25.00

When I was thirteen, my parents gifted me with the red and blue Beatles compilation CDs, the last CDs I used before I received my first iPod touch, which launched the rest of my young life into one dominated by the rapidly expanding digital musical world. Until that point, my perennial roadside companion was my Walkman portable CD player, a Christmas gift from five years prior. Once that Walkman was in my hands, there wasn’t a single car ride from that day forward where my headphones weren’t over my ears. Upon getting these Beatles CDs, I would snap one disc into that Walkman and not remove it for weeks on end, listening on repeat to a chronological parade of “Help!”—> “You’ve Got to Hide Your Love Away” —> “We Can Work It Out,” or a zigzagging permutation more like “Revolution” —> “Magical Mystery Tour” —> “A Day in the Life.” Regardless of how I listened, I absorbed those four discs to the point that I knew each little, musical inflection intimately.

Within the past month or so, I’ve come to the realization that to some degree, that period in my life may have been the last time I soaked up a record that intently, unfettered by the effects of digital music consumption on my listening practices. I’ve recently found myself in a sort of frenzy, experiencing the impulse to consume albums as rapidly as possible. I need to listen to this new release…I haven’t sat down yet with that record that’s been sitting in my streaming library for months…my friend recommended that album to me, I have to listen and follow up…. Sometimes I indulge my impulse and cycle through listening to records for the first time in rapid succession, acknowledging I listened to it before hastily moving on to the next record. I throw myself into these dizzying fevers of music consumption, gorging myself on a buffet of music, taking little tastes of everything for the all-you-can-eat price of $5 a month without sitting down and digesting.

Then, I realized in horror that I don’t just do this with music. This approach manifests in reading books, in watching movies, in getting my YouTube fix. It felt like my engagement with all forms of media was like one long television show that I kept binging episodes of. This epiphany made me notice how binge culture, in tandem with the streaming model, has created and reinforced a culture of passive listening habits that lack intention and reflection.

I’ve recognized for a long time that streaming enables passive listening. You are more likely on a streaming service to shuffle a playlist, pick and choose artists, albums, and tracks haphazardly out of sequence, and accept what is fed by the algorithm, than if you put your shoes on, flip through a record store bin, put your hard-earned money towards that specific record, and spin it on the turntable at home. Active listening. Putting your whole body into it, peeling your eyes away from your screen and letting your fingers graze along your record collection spines. I briefly touched on these points of active versus passive listening back in November with my post about streaming and data.

I believe the big difference between active and passive listening is intentionality. Whereas streaming music is simply handed to you, physical copies must be sought after. I’ve noticed this difference especially with reading books and magazines. Whereas an ebook might be handy when you’re waiting in line at the coffee shop, the reading is predicated on the fact that you need to simply fill time and its always there on your phone. On the other hand, bringing a physical book to the coffee shop to read for a few hours is active and intentional. Hard copies require intention. They demand to be acquired, acknowledged, picked up, and engaged with.

A few years ago, I read an insightful article by Michael Palm from The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies titled, “Keeping What Real? Vinyl Records and the Future of Independent Culture.” He wrote, “Streaming platforms reorganize music from ‘publishing’ media to ‘flow’ media, distinguished by Raymond Williams (2003) as being accessed rather than acquired by consumers. In other words, listeners morph from being music owners to music users.” This dichotomy between access and acquisition is at the root of how streaming changed the way we listen to music. Acquisition and ownership of music requires that intentional and choice, whereas streaming and access is fluid, impermanent, and impersonal.

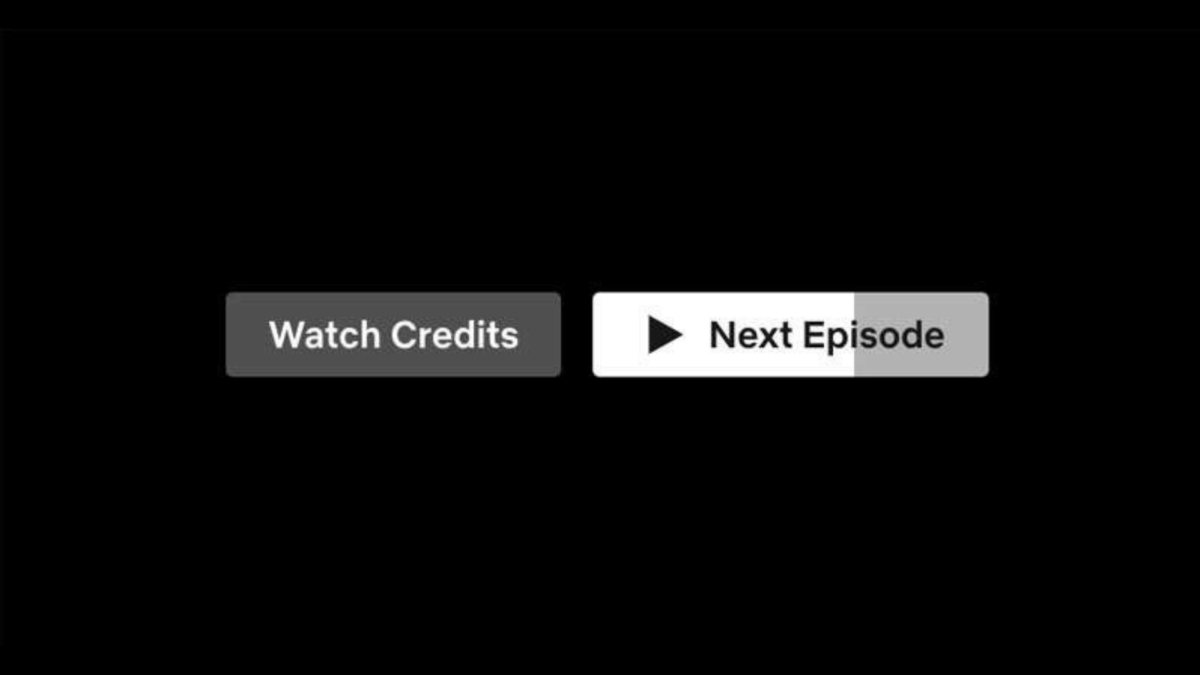

All of these changes forged by streaming services set the stage for binge culture. While the practice of binging is most associated with television streaming services, and was certainly engendered by the functions of Netflix and Hulu, the attitudes created by binging shows is not exclusive to television. The capacity to have anything you want only a tap or click away, the knowledge you can start or stop at any time, and the ability to simply add or delete without any repercussions allows for rapid, mindless, disposable consumption.

The first article that jumped out at me while researching binge culture was a JSTOR Daily post called, “A Critical Theory of Binge Watching,” which I highly recommend reading to supplement this blog. Jake Pitre cites numerous characteristics of binge watching throughout, such as the “bingeable TV lives of personalization, each viewer experiencing their own individualized interface and consuming their own niche segment of the culture.” I was struck by his description of “insular flow,” coined by Tanya Horeck, Mareike Jenner, and Tina Kendall in Critical Studies in Television. Not only are you binging a show, but when completed the service can autoplay another, taking away that element of choice. Music streaming implements the same feature, allowing the algorithm to choose a random selection of songs once the record you chose is finished, the function disconcertingly labeled with an infinity symbol on Apple Music. Even if you were actively engaging with a particular album via streaming, your mind can wander off afterwards while the machine offers you glimpses into music that no one chose, effectively numbing the process of reflecting on what you just heard. Why would we want to eradicate the beautiful silence after listening to a record that affects you profoundly?

Acquisition of physical media puts limits in place to impede the binge impulse. If ownership is the goal, finding time to go the record store, financial restrictions, and even physical space itself require elements of discretion and curation. I will admit I have a tendency to “binge” buy a bunch of records at a time, which may have roots in a streaming mindset, but it can’t compare to the deluge of records I can inundate myself with online. Often, I also feel as if I know the records I own better than the ones I’ve only streamed. You care more when you acquire a record because you see the direct transfer between hands, and you know its yours forever if you want it to be. But even using services such as a library takes time, such as waiting for holds or visiting the branch yourself. All of these practices have time built in to allow for digestion and reflection on what you’ve experienced. They encourage you to get to know a singular work inside and out instead of tossing it out in search of the next thing.

On my CD shelf today, the red and blue Beatles compilations remain, standing out with their bright hues and bulky size. The months of my life in which they sat inside my CD player left an imprint. Every lyric and lick is still memorized, every moment that manifested because I heard those songs lingers. I want to get to know records like that again, I don’t want to listen carelessly anymore. Fortunate for me, my portable CD player has followed me from place to place as I’ve grown older, tireless in its persistence that it still had something to offer my life. Now I just have to choose which CD to leave in there for several weeks, and take it on the road.

– Hannah Blanchette

February 1, 2025 | Blog