Designed to Live On: Townes Van Zandt

Often with singer-songwriters, we assume a level of authenticity between the person and the music, that what they sing represents who they are and what they’ve experienced. Sometimes this is warranted and true, in other situations a singer-songwriter performs tales of characters, reveling in fantasy. The country singer-songwriter Townes Van Zandt fascinates, as he somehow sits in-between, a figure who lived the ramblin’ life he sang about, while also telling tales of outcasts that are completely vivid with lives of their own. We recently restocked many Townes Van Zandt records, so before you delve into the tales in his music, take a brief look at the story of the man himself.

Townes Van Zandt was born John Townes Van Zandt in Texas, 1944 to a family of renowned civic leaders in the area, and Van Zandt was primed to follow in their footsteps. However, playing music would accompany, and eventually overtake, that journey starting at age nine. When Van Zandt saw Elvis on the Ed Sullivan Show, he asked for a guitar for Christmas. By the time Van Zandt began college at the University of Colorado at Boulder in the early sixties, he had developed a passion for poetry and playing guitar.

Throughout his first couple years of college, Van Zandt was popular with other students and achieved good grades. However, his parents became concerned that he was suicidal and drinking too much. As a result, Van Zandt was sent to a medical center for insulin shock treatment, a now widely discredited and discontinued form of treatment for mental illness. Many of those who knew Van Zandt believe the treatment caused considerable damage that lingered for the rest of his life.

After the treatment, Van Zandt went to the University of Houston for a fresh start in 1965, enrolling in a pre-law program, joining a fraternity, and marrying Fran, his girlfriend from Boulder. He also attempted to join the Air Force but was not permitted due to a bipolar disorder diagnosis. Throughout all of these ups and downs, Van Zandt still maintained an interest in writing and performing songs, and he decided to start performing in public.

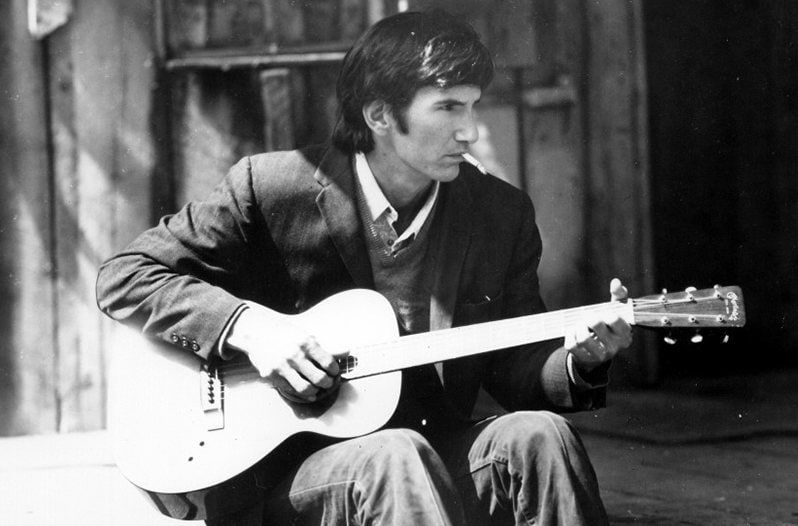

One of the first venues he frequented was the Jester Lounge in Houston, opening for folk, blues, and country legends like Doc Watson, Guy Clark, Jerry Jeff Walker, and Lightnin’ Hopkins. The latter was Van Zandt’s hero. Van Zandt repeatedly listened to Hopkins’ records while studying at Boulder, and in Houston had the opportunity to take guitar lessons from him. Van Zandt ended up developing a similar guitar style as Hopkins, using a pick with his thumb along with fingerpicking with his other fingers, easily visible in this performance of his hit “Pancho and Lefty” below from the documentary, Heartworn Highways (1976).

About a year into school at the University of Houston, Van Zandt’s father passed away. No longer facing the pressure to pursue law, Van Zandt left school and resolved to play music full-time, hitting the road with Guy Clark and Jerry Jeff Walker. At this point, Van Zandt’s life merged with the characters in his songs, fringe figures whose days contrasted between humor and gloom. As Texas Monthly pointed out, this can be heard in his early work like the song “Waitin’ Around to Die.” Van Zandt’s voice cracks over his insistent fingerpicked guitar as he sings about “lots of booze and lots of ramblin.’”

“Waitin’ Around to Die” was on Van Zandt’s first record, For the Sake of the Song, released on Poppy Records in 1968. While the arrangements on the record were more robust than simply hearing Van Zandt perform with his guitar, For the Sake of the Song firmly established Van Zandt as a skillful singer-songwriter. Later on, his self-titled album would re-release more stripped-down arrangements of some of these songs, showing the range of his sound and ability of his songs to fit just about anywhere.

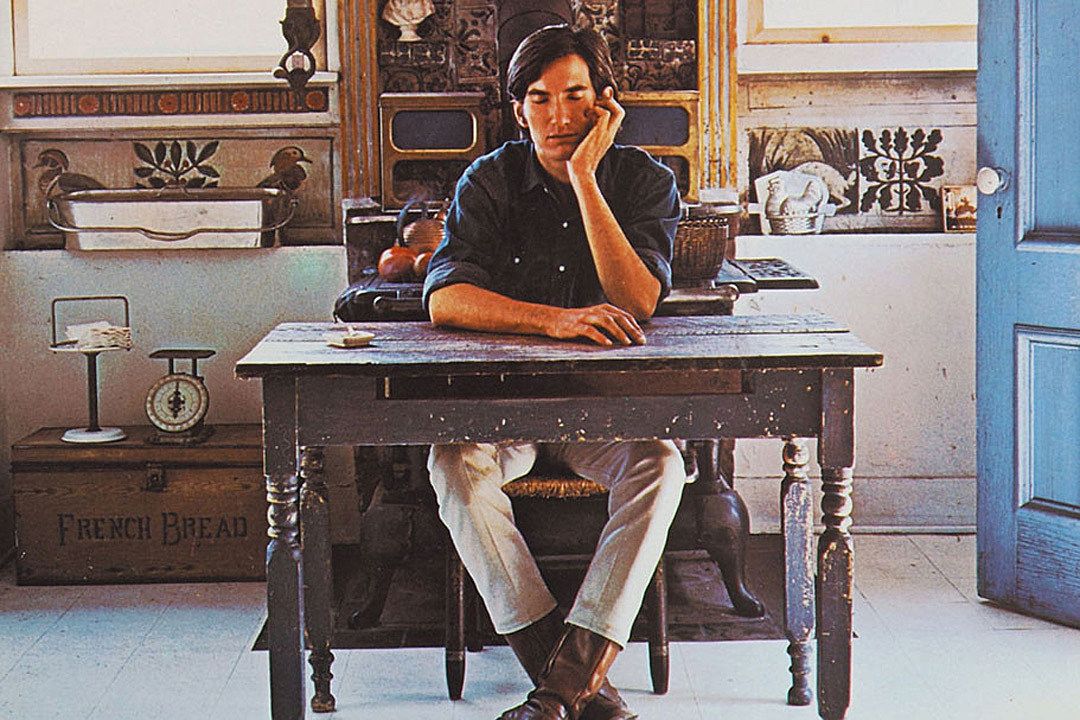

From his debut album onwards, Van Zandt truly followed an indie path, never releasing a record on a major label. He was even found in the early seventies hitchhiking around Texas with a bag full of his first two records, For the Sake and Our Mother the Mountain, with only the clothes on his back. Coming out of a divorce, Van Zandt traveled around Houston, Austin, Nashville, and New York during the seventies. Through 1977, Van Zandt released six studio albums and his acclaimed live album, Live at the Old Quarter, Houston, Texas. He was also featured prominently in the documentary Heartworn Highways, referenced above, a film capturing the essential figures of outlaw country, the term used to describe country artists working against mainstream trends of the Nashville sound, such as Willie Nelson, Kris Kristofferson, and Waylon Jennings. And although Van Zandt’s records didn’t reach the level of mainstream success of other country artists, even some of his outlaw contemporaries, his songs surely did.

Throughout his career and travels, Van Zandt won the admiration of many folk and country artists, some of whom recorded his songs, propelling them to great popularity. Emmylou Harris was a great fan of Van Zandt’s work, recalling the first time she saw him perform in the late sixties: “I thought he was the ghost of Hank Williams, with a twist.” In 1981, Harris, along with Don Williams, recorded Van Zandt’s “If I Needed You,” (originally on The Late Great Townes Van Zandt), achieving a No. 3 country hit with the song. Then in 1983, country giants Willie Nelson and Merle Haggard recorded “Pancho and Lefty” and shot to No. 1 on the country charts.

Van Zandt’s songwriting dwindled in the eighties and nineties, although he continued to perform and write. His lifelong struggles with alcohol and drug addictions were catching up to him, and he attended rehab multiple times. He passed away from a cardiac arrhythmia in 1997 at age fifty-two.

“I think my life will run out before my work does, you know? But I’ve designed it that way.” Van Zandt said this once, and in many ways, his work has lived on in the twenty-first century, from posthumous albums to influencing artists such as Gillian Welch, Simon Joyner, and Justin Townes Earle, the son of Steve Earle who shares Van Zandt’s namesake. When Van Zandt spoke those words above, maybe he was referring to his addictions causing health problems. But also, perhaps his songs were so relatable, voice so intimate, and guitar so artful that he knew his work was designed to live on long after his life ended.

In the Shop

Townes Van Zandt – The Best Of – $24

Townes Van Zandt – Delta Momma Blues – $20

Townes Van Zandt – Flyin’ Shoes – $22

Townes Van Zandt – For The Sake Of The Song (Olive Green Vinyl) – $23

Townes Van Zandt – In The Beginning – $22

Townes Van Zandt – Sky Blue – $22

Townes Van Zandt – S/T – $22

For more great finds, check out the folk and country section!

Resources

Brian T. Atkinson, “Mr. Record Man: Townes Van Zandt,” Lone Star Music Magazine (2011)

Be Here to Love Me, dir. Margaret Brown (2004)

Rebecca Bengal, “Booze and Ramblin’: The Blue, Wandering Life of Townes Van Zandt,” The Guardian (2019)

Alan Bisbort, “Townes Van Zandt: For the Sake of the Song,” Please Kill Me (2022)

Michael Hall, “The Great, Late Townes Van Zandt,” Texas Monthly (1998)

Heartworn Highways, dir. James Szalapski (1976)

John Kruth, To Live’s to Fly: The Ballad of the Late, Great Townes Van Zandt (2007)

– Hannah Blanchette

September 18, 2022 | Blog