Delayed Saxophones and the Downtown World of Dickie Landry

The saxophonist, composer, artist, and photographer Dickie Landry set out into the artistic world with the goal of crafting an individual sound unlike any other. From his distinctive stereo delay technique to create “a choir of saxophones” to the elaborate, mesmerizing solos he performed with his 1970s downtown scene contemporaries, Landry accomplished just that over a career spanning decades.

Dickie Landry was born in the small Louisiana town of Cecilia in 1938, his family involved in the sugarcane industry with their own sixty-five acre farm. One of his earliest musical experiences involved him sitting under the power distribution line on the farm, using the line’s hum as a drone to sing melodies on top of. When Landry was ten-years-old, his older brother John gifted Landry his old saxophone before John joined the Air Force. Landry practiced saxophone all day because he realized his parents wouldn’t disturb his practice sessions for farm work. While John played with the Air Force jazz band, he sent his brother jazz recordings of prominent saxophonists of the day. However, hearing Charlie Parker live was what really changed Landry and made him interested in more experimental approaches to saxophone, leading him to listen to performers like Albert Ayler and Ornette Coleman.

The Village Gate venue

The latter became friends with Landry in an encounter that sounds like a free jazz legend. Landry moved to New York City in 1969, after visiting various times throughout his life up until that point, becoming familiar with the downtown scene there. The second he arrived in the city in 1969, Landry’s possessions, including his saxophone, were stolen from his car. That night, he went to The Village Gate to hear Ornette Coleman perform. While Landry struck up a conversation with Coleman, he mentioned being robbed earlier that day and Coleman passed along his phone number, telling Landry to let him know if he needed a saxophone while in town.

Landry fit right in with the downtown scene, a polymath with skills in music, art, and photography. He recalled seeing a Time article in high school about artist Robert Rauschenberg and said, “I figured that if this man can do what he did and get this sort of attention, then I’m free to do whatever I want. The image cut all ties to classical and the jazz world…I wasn’t going to play saxophone like anybody else.”

Meeting Philip Glass provided one of the paths for Landry to play saxophone in a completely unique way. Following a dinner with Glass and fellow composer Steve Reich, Glass asked Landry if he would like to join his new ensemble, which would come to be known as the Philip Glass Ensemble. Landry was at the center of a musical movement known as minimalism, but which Glass considered more as “process music.” The first piece the original ensemble rehearsed was Music with Changing Parts, including the musicians David Behrman, Jon Gibson, and Frederic Rzewski. Glass’ music was incredibly challenging, as it required all of the ensemble playing the same rhythm, making any performance mistakes painfully obvious.

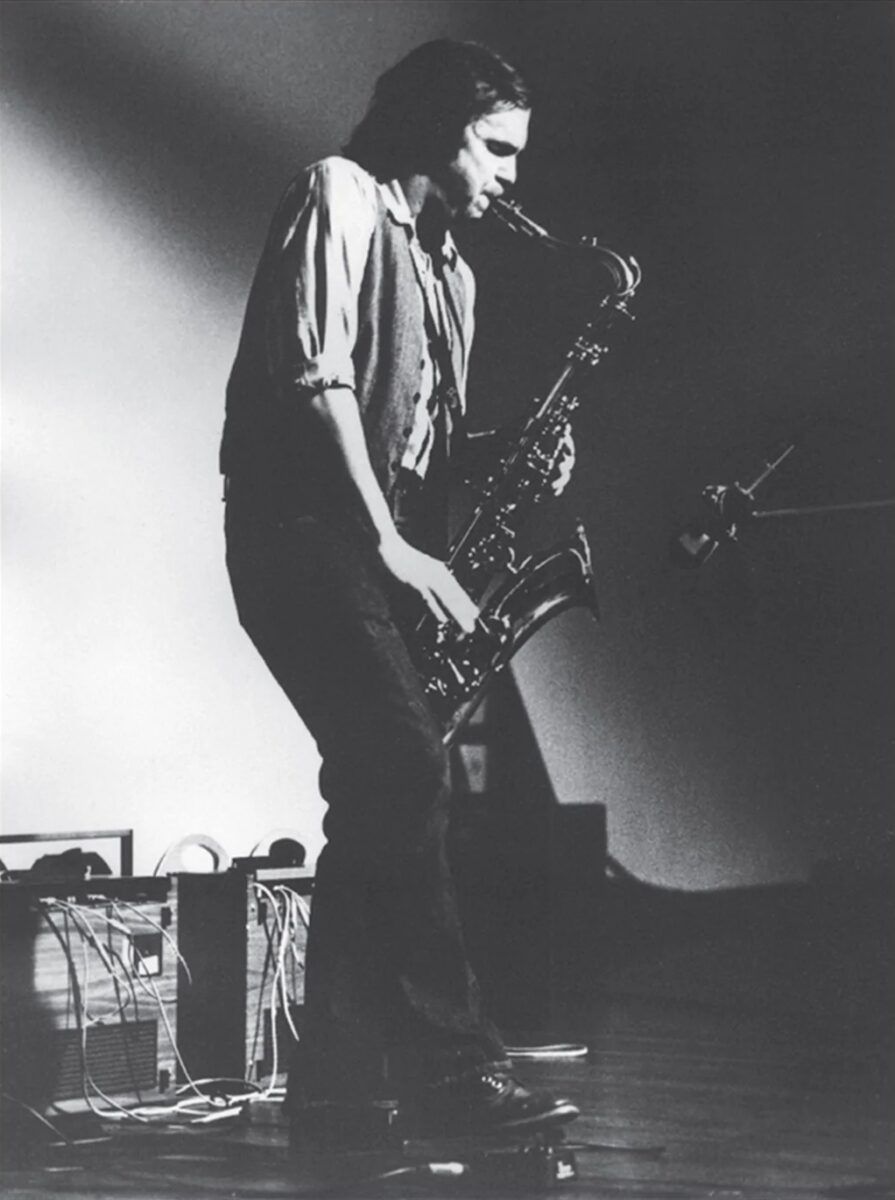

The Chatham Square ensemble for Solos

Landry lived with fellow musicians at 10 Chatham Square, whose namesake would eventually become the name of Philip Glass’ record label, and the label he would release his original recordings on. Landry and his Chatham Square peers jammed from 10pm until six in the morning. One day they landed a gig at Leo Castelli’s gallery and decided to do exactly what they did at home for the performance. Landry’s album, Solos, originally released in 1973, was born. The record feels like it starts in media res, throwing the listener right into the fray. Much of the music is active, always bustling as one performer bursts through the texture as the soloist, maybe only to be overtaken by another at any moment. Other tracks are more relaxed, the atmosphere sparser as the instrumentalists converse with each other, more so than butt in and interrupt.

The same musicians performed on an earlier release, 4 Cuts Placed in A First Quarter (1972), which provided the soundtrack for a film by the concept artist Lawrence Weiner. Landry simply followed Weiner while filming and hit play on the tape player whenever Weiner needed music. The pair continued to collaborate on the record Having Been Built on Sand, which combined Landry’s woodwind performances with Weiner’s recitations.

Through these experiences, Landry developed his signature improvisational technique involving stereo delays and overdubs. Through setting up as many delays as possible, Landry was able to create a choir of saxophones to complement his “stream-of-consciousness improvisation.” Speaking about his record Fifteen Saxophones (1977), Landry said, “When I performed solo, it was not about composition but about the instrument, its sound and its capabilities, I wanted to see how far I could take Adolphe Sax’s invention, the saxophone.” The title track of the record clearly illustrates the choir of saxophones that Landry’s delay process created, a murky wash of melancholy saxophones calling out to and responding to one another.

Landry’s time with the Philip Glass Ensemble ended in 1981 after Landry’s son was suddenly and tragically killed. Landry left New York and returned to Louisiana for a few years to process the grief. Upon returning to the city, Landry forged some new relationships and rekindled old ones. Laurie Anderson hooked him up with a gig right after he returned, and Landry reconnected with David Byrne, who brought him into the Talking Heads recording sessions for Speaking In Tongues (1983). Landry says, “If you listen to ‘Slippery People’ on Speaking In Tongues, the solo at the end that sounds like some sort of weird electronic instrument is my saxophone.”

To this day, Landry is as active as ever, from touring with his longtime collaborator, the playwright Robert Wilson, to tending to his forty-acre pecan farm. We just stocked the three recent reissues of Landry’s recordings by Unseen Worlds. Grab one to experience a sliver of the dizzying and spellbinding work of an artist who felt the freedom to not sound like anyone else.

In the Shop

Dickie Landry – 4 Cuts Placed In “A First Quarter” – $23

Dickie Landry – Solos – $34

Dickie Landry & Lawrence Weiner – Having Been Built on Sand – $23

See all in stock from Unseen Worlds and check out more free jazz and modern composition!

Resources

Dickie Landry’s official website

Clifford Allen, “Richard Landry,” Paris Transatlantic (2010)

Brandon Bell, “Be Somethin’: The Eclectic Career of Richard ‘Dickie’ Landry” (2019)

Yukie Ohta, “Dickie Landry’s New York,” SoHo Memory (2017)

Antonio Poscic, “Reissue Of The Week: Three Albums By Dickie Landry,” The Quietus (2022)

“Quad Suite: Richard Landry,” University of Louisiana at Lafayette

“Richard Landry: Solos, 1972: A Conversation with the Artist,” Castelli Gallery

– Hannah Blanchette

November 27, 2022 | Blog