Arvo Pärt, Sarah Davachi, and the Spectrum of Spirituality in Minimalism, From Sacred to Secular and What Lies Between

In the past few weeks, I was struck by two recent releases, one brand new and the other a reissue of a legendary recording in modern composition. The former is Sarah Davachi’s new album, The Head As Form’d in the Crier’s Choir, and the other, the new reissue of the essential ECM New Series recording, Arvo Pärt’s Tabula Rasa, originally released in 1984. Both composers interact with religious topics and spaces in very different ways. Davachi’s work is not religious in nature, but she has acknowledged the role of the organ in religious spaces and how she consequently engages with these spaces to perform her music. Pärt notably converted to Eastern Orthodoxy in his lifetime, causing his religion to greatly inform his music by reflecting his own interior, spiritual world. Considering Davachi and Pärt both as practicers of minimalism, I wish to use this entry as an exploration of the complex relationship between spirituality and minimalism, and the broad spectrum of how a composer interacts with these areas.

Themes of spirituality and minimalism have made brief appearances in some of my previous writing here, such as in a recent post’s allusion to La Monte Young’s and Meredith Monk’s turtles, who reminded them of slowness and presence of mind. Years ago, my piece on Eliáne Radigue touched upon the influence of Buddhism on her pioneering drone work. I find that minimalist works tend to allow the space for reflection that intertwines with a spiritual life. And while this can obviously be associated with drone, which has roots in numerous religious practices and appears in various Western genres spanning the avant-garde to folk music, I think even minimalism in the Philip Glass or Steve Reich vein can encourage spiritual practices of introspection and meditation.

Think of the experience of listening to Reich’s Music for 18 Musicians. It creates constant motion for almost an hour, each of the musicians working in tandem to form a fairly homogenous texture that manifests change through the minute shifts in timbre as each instrument moves in and out of the foreground. While listening, I often start by fixating on following these timbral changes and hearing how a simple melody transports throughout the ensemble, but eventually my mind wanders into contemplation. I don’t necessarily believe this is a bad thing. But what is it about that piece that elicits that response?

While considering this topic, I recalled a book that I impulsively grabbed for four dollars on a Friends of the Public Library bookstore jaunt ages ago. I completely judged the book by its cover and purchased it without thought, as the book is titled, Inside the Music: Conversations with Contemporary Musicians About Spirituality, Creativity, and Consciousness, with the interviewees listed on the cover including Allen Ginsberg, Leonard Cohen, Philip Glass, Meredith Monk and many others. Both Glass and Monk discuss Buddhism and meditation, with Glass reflecting on how they help with understanding your own mind, while Monk talks about how they help her understand the voice. Published in 1997 by Dimitri Ehrlich, he writes that through his conversations with these musicians, his definition of spirituality became, “an understanding that the material world is not the end of the story, that things are impermanent, almost dreamlike. It’s what I call a ventilating worldview, in which phenomenal reality seems less solid, somehow more airy and permeable.”

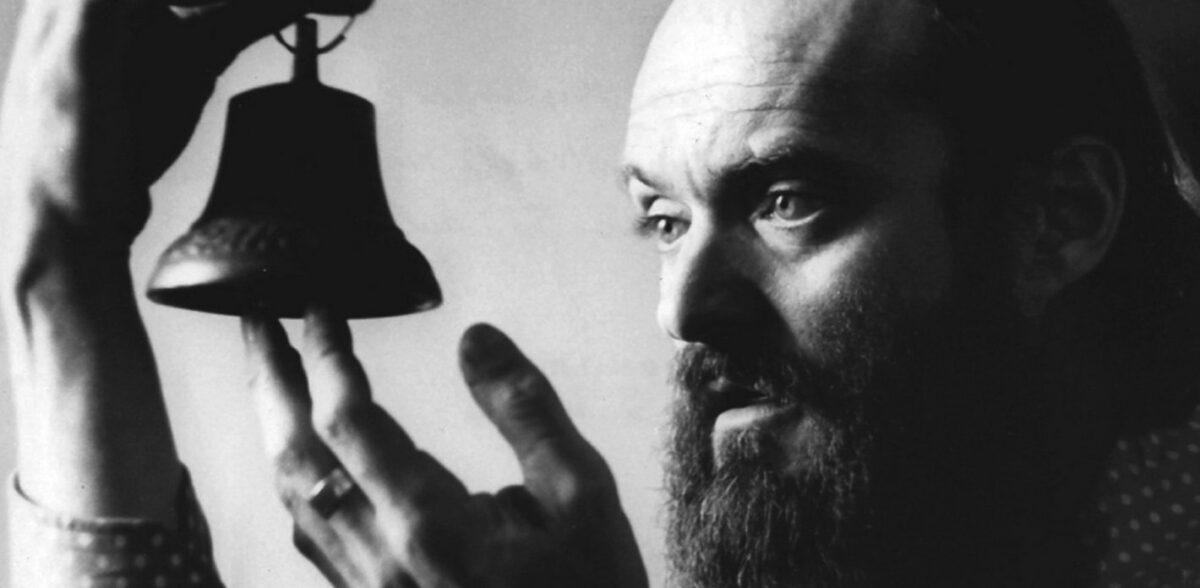

Arvo Pärt is an Estonian composer working in the minimalist style since the seventies. His pieces have been influenced by medieval chant and Renaissance church music, and his first sacred work, Credo (1968) forged a crossroads in his career because his compositions were subsequently censured by the Soviet Union. The aspect of Arvo Pärt’s work, or more specifically its reception, that intrigues me is how despite the knowledge of Pärt’s relationship with Eastern Orthodoxy, his compositions are often interpreted in a more broadly spiritual way akin to Ehrlich’s definition above, even by Pärt himself. As William Robin wrote for The New York Times in 2014, “The global classical music market has mediated — or perhaps tamed — his religion, opening up the iconography of the Orthodox Church to a broader mysticism.” Even descriptions of Pärt’s compositional technique, tintinnabuli, gesture towards a more generalized sense of spirituality than religious specifics. Dr. Peter Bouteneff of St. Vladimir’s Orthodox Theological Seminary describes tintinnabuli as “the melody voice, which is the human straying, and the triad voice, which represents the divine stability and consolation.”

Pärt himself frequently distances himself from a direct correlation between Eastern Orthodoxy and his work, positioning it as more a representation of his inner self, which includes his sense of spirituality. As I listen to Tabula Rasa, especially the first movement, the constant returns to the opening motif are what strike me as vaguely spiritual, a feeling akin to repeating a certain text or coming back to a meditative center. It feels like being drawn back to that center again and again, a wandering or straying that keeps resetting. I interpret this music this way, Pärt intended it his own way, and you might feel differently upon experiencing it yourself. Pärt has said, “I am not taking the task in my music to discuss some religious or special Orthodox values. I am trying to reflect the values in my music that could touch every individual, every person.”

Where the spiritual connotations in Pärt’s music comes from his own history, Sarah Davachi’s emerges most from the instrument she plays. Writing and performing on organ results in engaging with the religious history of the instrument and with the religious spaces where organs reside. I wrote earlier this year about the prevalence of organ in current experimental music, including Davachi. Her approaches to the organ and electroacoustic music seem to be more from a place of appreciation for Baroque music, such as Bach’s organ compositions, combined with her love of drone from the aforementioned Eliáne Radigue and La Monte Young. Consequently, there is an antiquity to her music shaped by the lens of modernity. Interestingly, Davachi’s new record, The Head As Form’d in the Crier’s Choir, derives conceptually from the ancient Greek myth of Orpheus, alluding to the spiritual realm of a time centuries before the organ’s existence.

Davachi has not shied away from discussing her complicated relationship to religious spaces and their influence on her music, as well as how her compositions can be interpreted as spiritual for some listeners. In a 2018 Aquarium Drunkard interview, Davachi recalls: “When I travel, I always like to check out local cathedrals, because I think they’re beautiful buildings and the acoustics are nice. But this trip, I noticed more the feeling of sitting there, being in this very different space from the outside world, being able to sit and not do anything. That became important and influenced the way I was thinking about the music. It made me want to tap into that feeling….Those moments, of ritualistic quietude — the music became an extension of that.” The way she speaks about these experiences is in step with her forebears I spoke of at the top of this piece, and aligns with my own theories of the frequent merging of spirituality and minimalism.

In the AD interview, Davachi also notes the challenges she faces with not supporting religion personally while drawing inspiration from these spaces. It’s a complex exploration of the line between the sacred and the secular, and how one positions themself in relation to these binaries. Davachi describes how she views her work through a more secular mystical perspective than spiritual, as well as encouraging deep listening, stating, “What I wanted to force people into with my music was this way of actually listening. I found that people are so impatient, they gloss over the things you should be listening for in sound. From a scientific standpoint, sound is such a fascinating thing we don’t explore in detail….Maybe worshipping is a stupid word, but at least paying homage to sound itself as opposed to any extramusical thing beyond it.”

So where are the boundaries amongst secular, sacred, spiritual, deep listening, drone, minimalism, etc.? These concepts borrow, influence, and conflict with one another, and many composers participate in their dance when they step foot into one or more of their realms. Spirituality and minimalism do not go hand-in-hand, but don’t ignore each other either. At the end of my musings here (which have to stop because I could probably write a whole book on this topic), all I can say is that it is messy, which I find beautiful. These concepts are not black and white, not easily wrangled into boxes, and shouldn’t be so.

– Hannah Blanchette

October 20, 2024 | Blog