-

×

Sun Ra and his Intergalatic Friends - Dieswarts CS

1 × $10.00

Sun Ra and his Intergalatic Friends - Dieswarts CS

1 × $10.00 -

×

Bass Communion – Ghosts On Magnetic Tape

1 × $25.00

Bass Communion – Ghosts On Magnetic Tape

1 × $25.00

Subtotal: $35.00

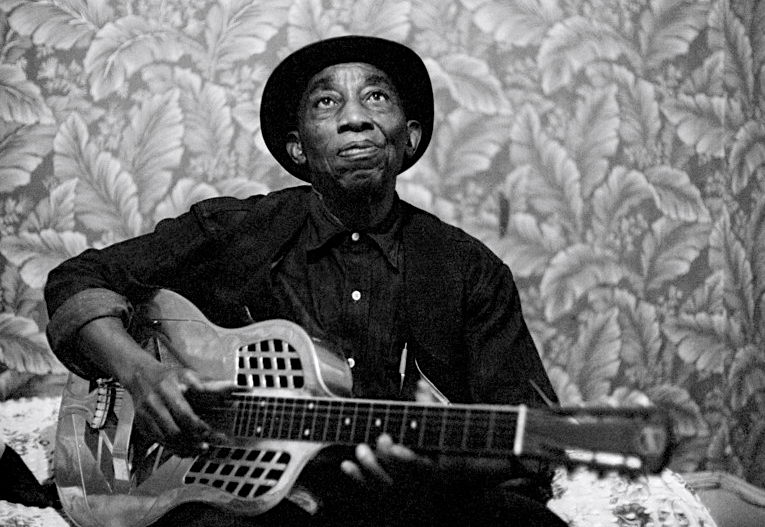

Beloved blues artist Mississippi John Hurt had a saying, “Don’t die ‘til you’re dead.” Hurt lived up to his wisdom, experiencing a life of work, playing and recording blues, and mesmerizing audiences with his gentle voice and intricate fingerpicking guitar style through his old age. From Avalon, Mississippi to Newport, Rhode Island, and many stops in-between, we take a look this week at the life and music of Mississippi John Hurt.

Beloved blues artist Mississippi John Hurt had a saying, “Don’t die ‘til you’re dead.” Hurt lived up to his wisdom, experiencing a life of work, playing and recording blues, and mesmerizing audiences with his gentle voice and intricate fingerpicking guitar style through his old age. From Avalon, Mississippi to Newport, Rhode Island, and many stops in-between, we take a look this week at the life and music of Mississippi John Hurt.

Born in 1892, Mississippi John Hurt grew up in Avalon, Mississippi, a small community at the time with a post office, general stores, gas station, and railroad depot. Hurt began teaching himself guitar around age nine, developing a distinctive fingerpicking style inspired by a local elderly player, Rufus Hanks. His guitar playing was also influenced by another frequent visitor to the Hurt home, William Henry Carson. One time, Hurt’s mother thought the person playing in the house was Carson, and when she discovered the talented performer was actually her young son, she bought Hurt his first guitar, which he named “Black Annie.”

Avalon would consistently draw Hurt back throughout his life, whether by physically moving back or through his music. This is especially apparent in one of his first recorded works, “Avalon Blues,” in which Hurt sings, “Avalon, my hometown, always on my mind,” along with the lyrics, “New York’s a good town, but it’s not for mine.” At the time of recording in 1928, Hurt was traveling to New York and Memphis to make records for Okeh Records. Hurt entered the recording industry through his friend and collaborator, fiddler Willie Narmour. After Narmour won a contract with Okeh from a fiddling contest, he recommended Hurt to the label as well.

During this time period, Okeh Records were known for their “race records,” a marketing and genre category for 78-rpm records in the early twentieth-century record industry. Race records were marketed for an African American demographic, and frequently sold records in genres recorded by predominantly Black performers, such as blues. The other main genre category marketed by record labels during this time period, including Okeh, were “hillbilly records,” which were mostly old-time and country recordings geared towards white audiences. Mississippi John Hurt’s music often defied these literally Black-and-white categories, and throughout his time on Okeh, his recordings were sold under the race and hillbilly records umbrellas.

This can be attributed to Hurt’s musical style, which has come to be referred to as country blues, a style of blues developed in the Mississippi Delta region and characterized by its instrumentation of solo voice and guitar (plus harmonica sometimes). Country blues contrasted with the blues of artists such as Bessie Smith or Ma Rainey, which had a piano or band accompaniment and drew upon musical characteristics of vaudeville. As a Smithsonian Folkways article writes, “The country blues is the music of day to day life. It is the lonely music of lounging on the front porch, the rowdy music of the house party, and the raucous and engaging music of the concert stage. The lyrics deal with the African American experience and the hardships of work, life, and love in the American South, and themes of travel, loneliness, and wandering of the blues musician lifestyle.”

After releasing his 1928 Okeh recordings, Mississippi John Hurt returned to Avalon. The records did not fare well commercially, especially during the Great Depression, which also put Okeh Records out of business. Hurt took up work on farms and railroads, and performed locally at parties and other social events. However, in the 1950s, interest in Hurt’s music began to increase. Part of this was due to the 1952 Folkways record, The Anthology of American Folk Music, which included his “Frankie” and “Spike Driver Blues.” The other major figure was Tom Hoskins, a folk musicologist who found Hurt’s “Avalon Blues” recording. Hoskins decided to travel to Avalon and see if Hurt happened to still live there. Once Hoskins met Hurt in Avalon, the wheels were set in motion for Hurt to become a major figure in the sixties blues and folk revival.

Hurt’s widespread acclaim began with his performance at the 1963 Newport Folk Festival, amongst other rising and established folk and blues greats such as Bill Monroe, Doc Watson, Clarence Ashley, Joan Baez, Brownie McGhee, Bob Dylan, Bessie Jones & The Georgia Sea Island Singers, Jean Ritchie, John Lee Hooker, and Pete Seeger. For the next three years until his death in 1966, Hurt made recordings for Vanguard and the Library of Congress, and toured with contemporaries Elizabeth Cotten, Mississippi Fred McDowell, Sonny Terry, Rev. Gary Davis, Brownie McGhee, and John Lee Hooker. He also appeared on Pete Seeger’s folk television program, Rainbow Quest in 1965, creating one of the most intimate video recordings we have of his endearing performance style (below).

Mississippi John Hurt was also interviewed more in-depth by Pete Seeger, with the recording of that interview released for the first time on Memorial Anthology, a 2xCD compilation from the 1990s of Hurt’s works . Many compilations have come in the years since Hurt’s death, celebrating his life’s work.

We also have this cassette compilation of his 1928 recordings in stock, from the classics like “Stack O’ Lee Blues” to the game changers such as “Avalon Blues,” available in the shop and online. Also take a look at our online section of folk, country, and blues to find more gems of these genres!

“American Folklife Center Collections: Mississippi,” Library of Congress [for more to explore about Mississippi]

Mary Frances Hurt and Ed Levine, “‘Today!’–Mississippi John Hurt (1966),” Library of Congress (2009)

Steve James, “Gaslight Memories: Mississippi John Hurt’s Influence on the 1960s Folk Scene and Beyond,” Acoustic Guitar (2018) [a great article to check out for more info on his guitar style!]

Jessica Keyes, “The Country Blues: Rural Soul Music of the Southern USA,” Smithsonian Folkways

“Mississippi John Hurt,” The Mississippi Blues Trail [cool digital exhibit!]

“‘Mississippi’ John Hurt,” National Park Service (2017)

“MJH Bio,” The Mississippi John Hurt Foundation [learn more about the foundation here too]

JD Nash, “10 Things You Didn’t Know About Mississippi John Hurt,” American Blues Scene (2020)

Ken Perlman, “Melodic Clawhammer: Translating Mississippi John Hurt’s Country Blues to Clawhammer,” Banjo Newsletter (2021) [for interested banjo players]

John Zheng, “Avalon and Valley: Mississippi John Hurt’s Blues Base,” Mississippi Folklife (2020) [beautiful essay and photography of Avalon, highly recommend]

– Hannah Blanchette

April 10, 2022 | Blog